US spy agencies face ‘shocking’ lack of diversity

Former CIA officers say diverse workforce needed to confront complex threats

This report is part of "Turning Point," a groundbreaking series by ABC News examining the racial reckoning sweeping the United States and exploring whether it can lead to lasting reconciliation.

As the Trump administration rolls back initiatives meant to bolster diversity and inclusion across the federal government, U.S. spy agencies are working to expand minority representation in their ranks and counter what some experts see as a looming threat to national security.

For years, the intelligence community -- made up of 17 federal agencies, including the CIA -- has had one of the least diverse workforces in government, despite the fact that its mission is to analyze intelligence in dozens of languages and understand the nuances of diverse cultures in order to identify complex threats.

Just 26.5% of members of the intelligence agencies in 2019 were racial and ethnic minorities, up slightly from 26.2% in 2018, according to a new report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence obtained by ABC News.

The figures are below the level of representation across the federal government -- 37.1% -- and the civilian labor force -- 37.4% -- overall.

"It's a practical equation. It's not even about right or wrong. It's about what they need as a foreign intelligence service," said Douglas London, a 34-year CIA veteran who was stationed around the world. "Our adversaries and enemies are not going to be privileged, white suburbanites walking around the streets in Southern California."

"A large body of our spies are not really up to the challenge of dealing with different people and relating to them in an effective way," added London.

The disparity has been more pronounced at the top. At the Central Intelligence Agency, the nation's premier spy organization, just 10.8% of its leaders were people of color in 2015, according to a declassified report. The agency declined to provide ABC News with the latest figures.

"What was shocking to me was just the lack of representation of diversity in its senior ranks especially, but across the board in the (intelligence community)," said Rep. Terri Sewell of Alabama, an eight-year member of the House Intelligence Committee.

"There's a lot of lip service that goes on with talking about diversity and not enough action, intentional action," Sewell told ABC News, "especially when you think about the fact that there are some (minority recruits) that come in and get diverted to administration roles and not into mission critical."

Current and former intelligence agency leaders and officers, including members of both political parties, say the marginal improvement in diverse hiring and promotion in recent years is insufficient.

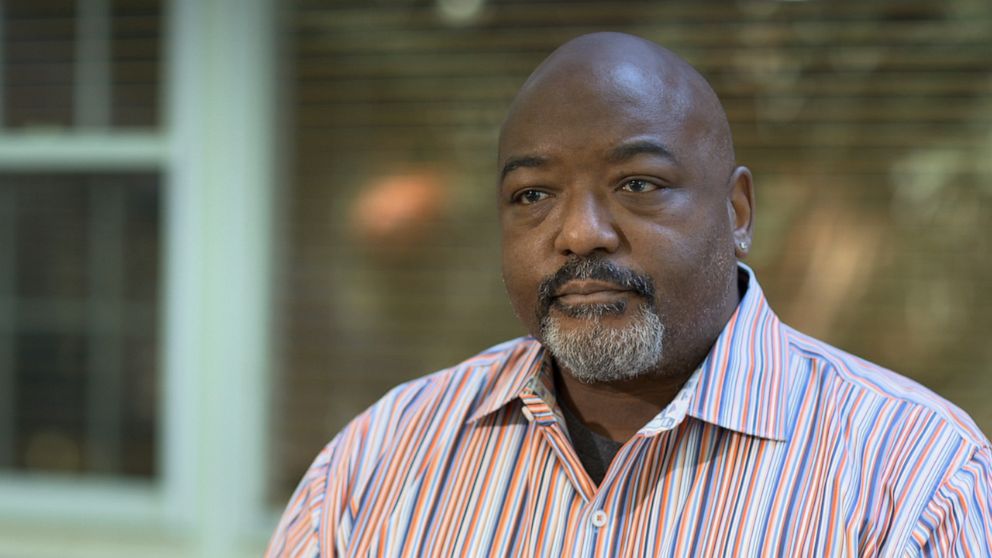

"I would never be satisfied with the numbers," said Darrell Blocker, a retired CIA officer who is African American and spent decades gathering intelligence overseas and helping recruit future American spies in the U.S. "Diversity and inclusion training is extremely important."

In cracking down on diversity initiatives, the White House denies there is deep-seated racial bias and white privilege and has outright banned race-related trainings at federal agencies, including CIA.

"I ended it because it's racist. I ended it because a lot of people were complaining that they were asked to do things that were absolutely insane," President Donald Trump explained of his decision during the first presidential debate last month.

The CIA declined to say what steps, if any, it took in light of the president's order ending the trainings, but top agency officials say initiatives aimed at increasing diversity in the workforce are active and remain a top priority.

"Fostering diversity and inclusion is a key requirement for promotion into leadership positions, and we specifically train our officers how to create and maintain an inclusive workplace," said Sonya Holt, deputy associate director of CIA for talent for diversity and inclusion.

"We routinely facilitate discussions with our global workforce to talk about the complexities of diversity," Holt said.

This summer, the CIA launched its first-ever national streaming video ad targeting young, minority potential recruits. The agency also continues to foster ties with Historically Black Colleges and Universities for job recruitment initiatives.

"We created strong partnerships with academic institutions with diverse populations to ensure students have continued access to CIA to learn about the Agency careers available to them," said CIA chief of talent acquisition Sheronda Dorsey in a statement to ABC.

But after years of similar efforts, some wonder whether this latest push will be any more effective at attracting and retaining more diverse Americans as spies and analysts.

Former CIA officials say one of the biggest barriers is the stigma from the agency's controversial history of alleged human experimentation, torture and assassinations.

"It's a double-edged sword. The mystique is good. It helps us to have people think that we can do these things, but it also hurts us when they think we're doing things that we're not," said Blocker of his efforts to help recruit minority hires late in his tenure.

"You can get folks in the door, but it's retaining them and promoting them," said Sewell, who serves on the House Intelligence Committee.

"You will see this committee being engaged in setting benchmarks and goals and asking for more accountability by (having them give) us the numbers of ethic minorities broken down by ethnicity," she said. "But those are all classified. Therein lies the problem."

Blocker said he's optimistic the intelligence community is capable of evolving and that it's imperative that they do because of the challenges of rapidly changing and complex threats.

"When I walked in the door in 1990, there were zero examples of a division chief. When I walked out the door: Asians, Latina, Latinex, Black, like myself, division chief," Blocker said.

"I saw a lot of progress, but I don't know if it's sustainable progress," he added. "The agency needs to understand that if you're going to invest in some minority communities, you have to be there all the time."