More than a year after George Floyd's killing, Congress can't agree on police reform

Bipartisan efforts to substantively address the issue are officially over.

Talks of bipartisan police reform legislation in Congress are officially over as Republicans and Democrats can't agree on key issues.

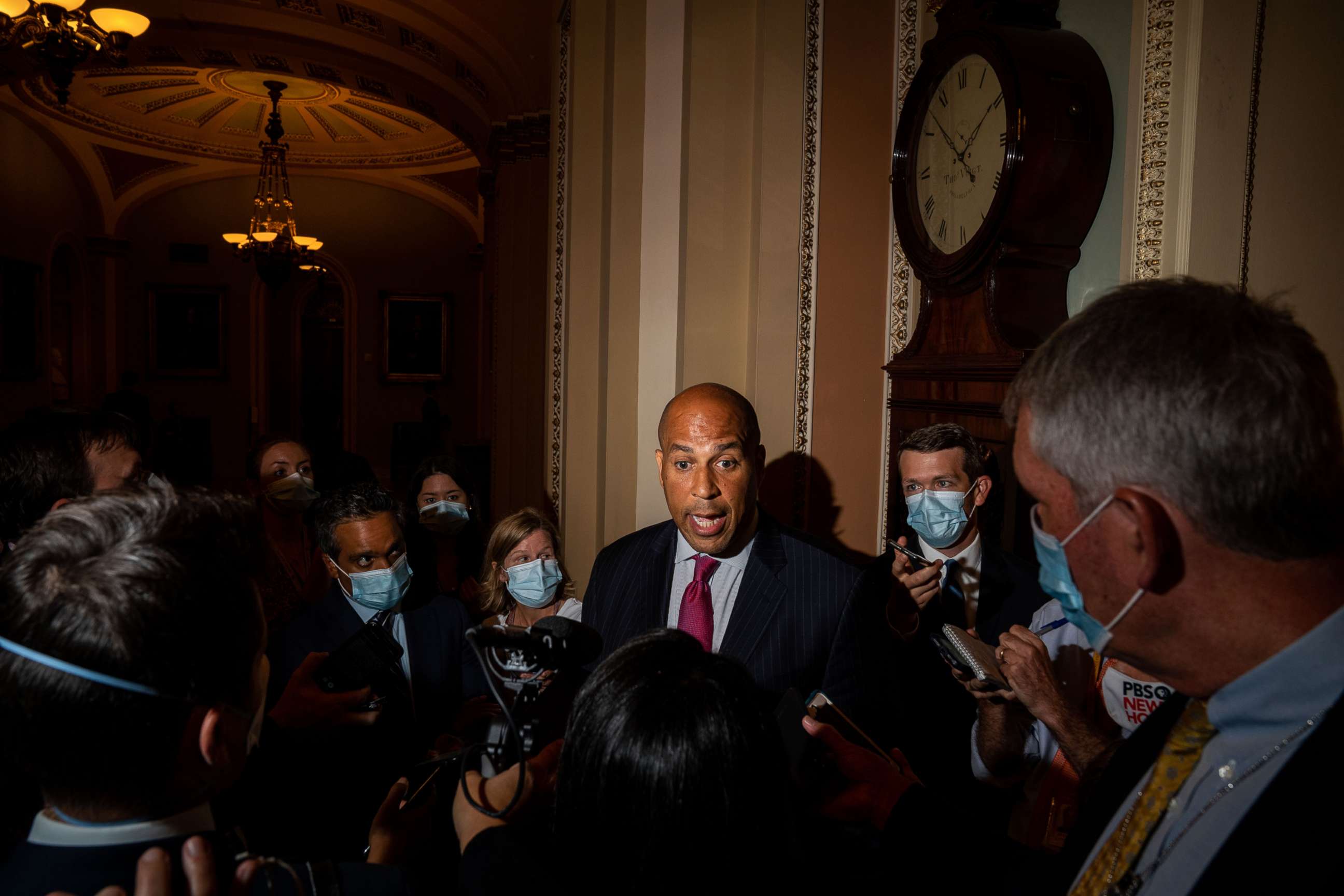

Democrats, after more than a year of negotiations, made a final offer, but despite "significant strides," said Sen. Cory Booker, D-N.J., there weren't any more concessions to be made.

"I just want to make it clear that this is not an end -- the efforts to create substantive policing reform will continue," Booker told reporters at the Capitol.

"It is a disappointment that we are at this moment," Booker continued, adding that having participation from nation's largest police union and the International Association of Chiefs of Police shows that "this is a bigger movement than where we were just a year or two ago."

Lead Republican negotiator Sen. Tim Scott, R-S.C., said he's concerned about high crime rates in some cities.

"When you're talking about making progress in the bill, and your definition of progress is to make it punitive -- or take more money away from officers if they don't do what you want them to do -- that's defunding the police," Scott told ABC News. "I'm not going to be a part of defunding the police."

More than a year after the start of a racial reckoning in the United States, the movement to address brutality and racism in policing continues to dominate political discourse.

George Floyd's death prompts reform

The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act was introduced in June 2020, very soon after Floyd, a Black man, was killed by then-Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin during an arrest. Floyd was accused of using a fake $20 bill at a local store.

Chauvin pinned Floyd on the ground, with his knee on the back of Floyd's neck and upper back until he went unconscious. Videos taken by bystanders sparked a national movement against police brutality and racism, and legislators, including Rep. Karen Bass, D-Calif., and Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, D-Texas, sought to answer calls for justice and end the current system of policing.

The Justice in Policing Act aimed to establish a national standard for policing practices, collect better data on police use of force and misconduct, ban the use of tactics such as no-knock warrants, and limit qualified immunity, which protects officers against private civil lawsuits.

It passed the House in March on a party-line vote, but the Republican-majority Senate didn't move it forward. The legislation was reintroduced in 2021.

Senate Republicans also proposed a reform bill in June 2020, but Democrats blocked it, saying it didn't do enough.

The Justice Act proposed using federal dollars to incentivize police departments to ban controversial practices, like the chokehold that killed Floyd, make lynching a federal hate crime, increase training and enforce the use of body cameras. The effectiveness of no-knock warrants also was to be studied.

Democrats and Republicans agree on 'framework'

In summer 2021, both sides settled on a shared "framework" from which to pursue legislation.

"After months of working in good faith, we have reached an agreement on a framework addressing the major issues for bipartisan police reform," Scott, Booker and Bass said in a joint statement. "There is still more work to be done on the final bill, and nothing is agreed to until everything is agreed to. Over the next few weeks we look forward to continuing our work toward getting a finalized proposal across the finish line."

Many Republicans said they believed the proposed legislation put law enforcement under attack, while most Democrats held firm in holding accountable officers accused of abusing suspects.

Qualified immunity

Both sides still agreed to pursue change, but qualified immunity quickly became a sticking point for Republicans, and it ultimately led to the legislation's demise.

Qualified immunity protects officers in cases where they've been individually accused of violating a person's civil rights.

Some congressional Republicans said they feared a rise in frivolous lawsuits if qualified immunity were to be eradicated, but officers still would've had the same constitutional protections, and civil cases still would've been reviewed by courts before moving forward.

Sources told ABC News that Scott would get on board with a proposal if police unions could agree on a plan, but they've been very reluctant to do so.

Two police unions, the Fraternal Order of Police and the International Association of Chiefs of Police, were involved in negotiations with legislators. Though they came close to an agreement with Booker, other police unions such as the National Association of Police Organization, spoke out against Booker's proposals because they weren't included in earlier discussions.

Now, it's back to square one. Booker said he and Congressional Democrats will find other pathways to achieving extensive police reform , but those pathways likely won't include Republican colleagues.

Vice President Kamala Harris, who was in the Senate at the start of these negotiations, denounced Republican efforts to quash reform.

"We learned that Senate Republicans chose to reject even the most modest reforms. Their refusal to act is unconscionable," Harris said in a statement. "Millions of people marched in the streets to see reform and accountability, not further inaction. Moving forward, we are committed to exploring every available action at the executive level to advance the cause of justice in our nation."

White House press secretary Jen Psaki said President Joe Biden was disappointed.

"In the coming weeks," she said, "our team will consult with members of Congress, the law enforcement, civil rights communities and victims families to discuss a path forward, including potential executive actions the president can take to ensure we live up to the American ideal of equality and justice under law."

ABC News Rachel Scott and Ben Gittleson contributed to this report.