Researchers are developing an energy-efficient wood for homes

Researchers have modified wood to make it stronger and able to cool itself.

This is an Inside Science story.

(Inside Science) -- Futuristic, energy-efficient houses may soon be made of -- wood. This staple of construction has received a makeover that gives it desirable properties such as increased strength and the ability to shed heat.

Researchers developed a process to convert wood into what they call “cooling wood.” They presented the details of this promising building material that could decrease the need for air conditioning in an article published today in the journal Science.

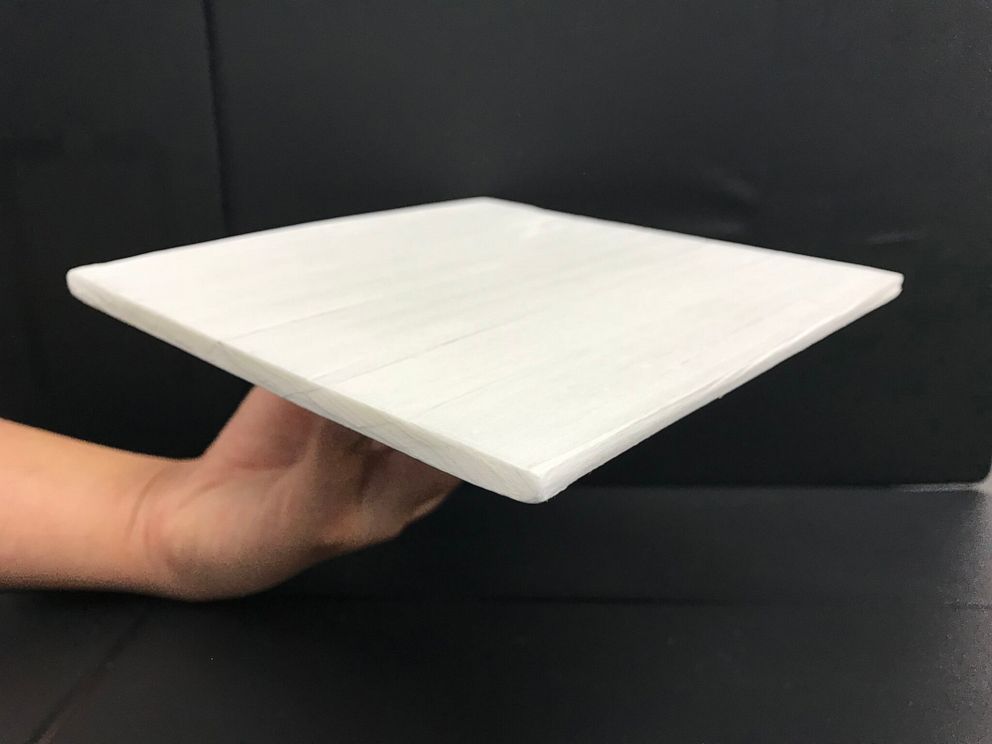

They first remove ligin -- a part of plants that contributes stiffness -- from a wood panel by boiling it in hydrogen peroxide, which after mechanical pressing results in a material made of densely packed, molecularly bonded cellulose fibers. The resulting material is much stronger and tougher than ordinary wood.

The process turns the wood white. The transformed material then reflects visible light instead of absorbing it. But that's only one part of why it stays cool. Additionally, the molecular vibrations of the cellulose are good at producing infrared radiation, which carries energy off into space, cooling the wood.

The combination of receiving little energy and being good at releasing energy means the wood cools itself. In an experiment conducted by the researchers in Arizona, the wood stayed on average about 16 degrees Fahrenheit cooler than the ambient temperature during nighttime and 7.2 degrees cooler during the middle of the day.

The researchers say that the passive cooling of the wood is most effective in a hot, dry climate and that if left exposed during cold periods the cooling wood could increase heating costs.

According to the U.S. Department of Energy, air conditioners use about 6% of all produced electricity produced in the country, costing homeowners about $29 billion and accounting for the release of about 117 million metric tons of carbon dioxide. So passive cooling, even if only applied in limited areas, could make a significant difference as energy demand from air conditioners around the world is projected to more than double by 2040, according to the International Energy Agency.

Inside Science is an editorially-independent nonprofit print, electronic and video journalism news service owned and operated by the American Institute of Physics.