Whale songs in the ocean around Antarctica have transformed; climate change could be why

Songs have lowered in frequency, in part because of changes to ocean water.

Whales in the ocean around Antarctica are changing their tune, according to a new study.

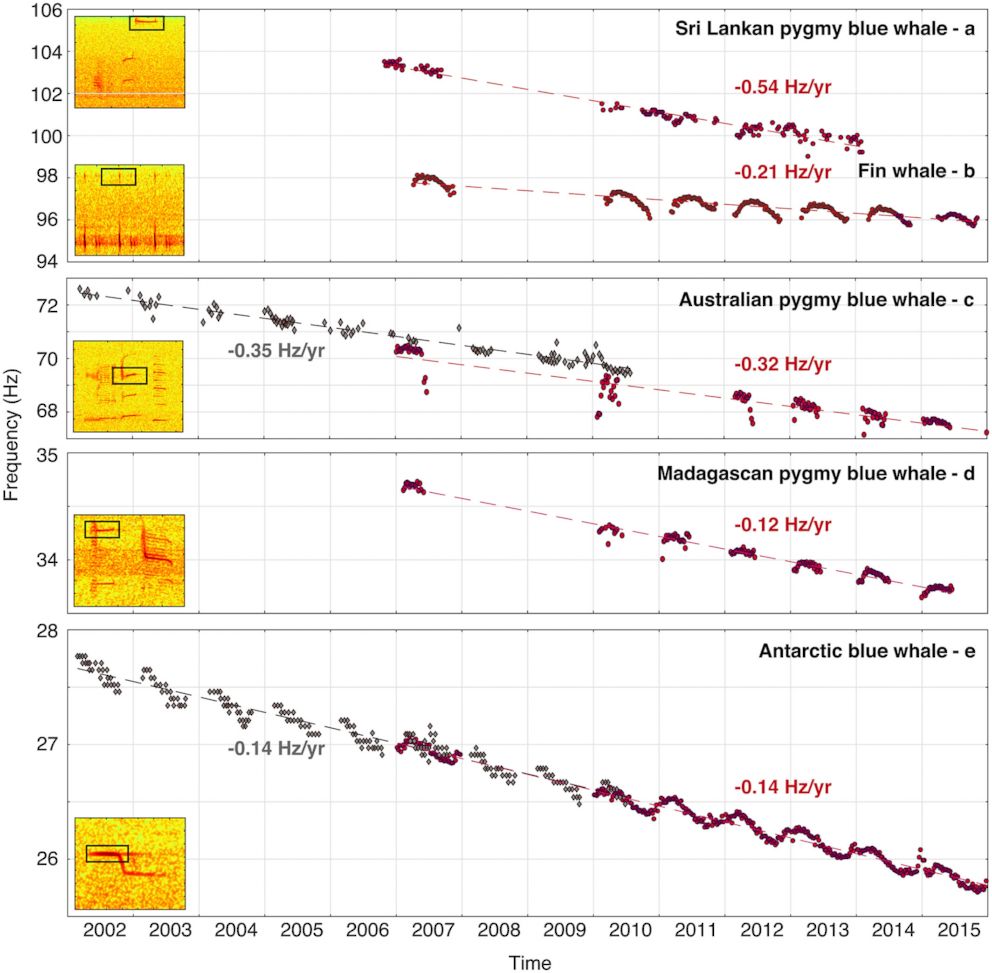

Publishing their findings in the Journal of Geophysical Research, scientists collected and analyzed more than 1 million songs from five populations of large whales in the southern Indian Ocean over the course of 7 years. They said that among other contributing factors, climate change and ocean acidification may have led to changes in the way that whales sing.

Male blue whales and male fin whales produce the loudest calls in the southern Indian Ocean, and their songs can be heard underwater up to 1,000 kilometers away, which enables them to maintain contact with each other.

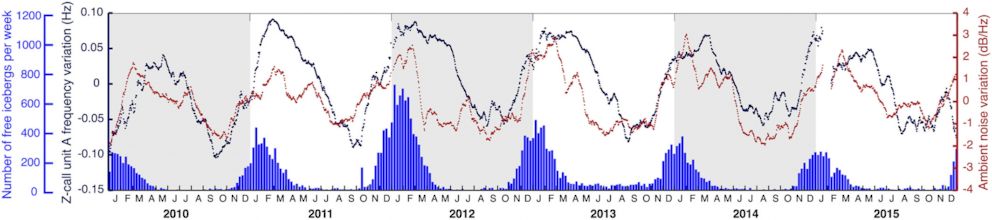

“We measured precisely the frequency of the first tonal sound -- called unit A -- in each detected call. We observed that over the years, this frequency has decreased by about 0.14 hertz per year,” Jean-Yves Royer, one of the authors of the study, told ABC news.

Royer explained that one of the reasons the whales have lowered their frequencies could be because an excess of carbon in the water as the oceans become more acidic.

“This chemical change induces a change in the acoustic properties of the ocean, acidification favoring the propagation of low frequencies,” said Royer. “All large whales emit low-frequency sounds, hardly discernible by a human ear. If the ocean carries better the sound waves, then no need to shout as loud as before to communicate with other whales.”

Royer said that other contributing factors to changes in whale calls in the region could be the increased frequency of of icebergs breaking, and growing whale populations.

“Since the whaling ban, the populations may have recovered so that there is no need for crying out as loud as before to communicate,” Royer said.