'It's just crazy': 12 major cities hit all-time homicide records

"It's worse than a war zone around here lately," police official said.

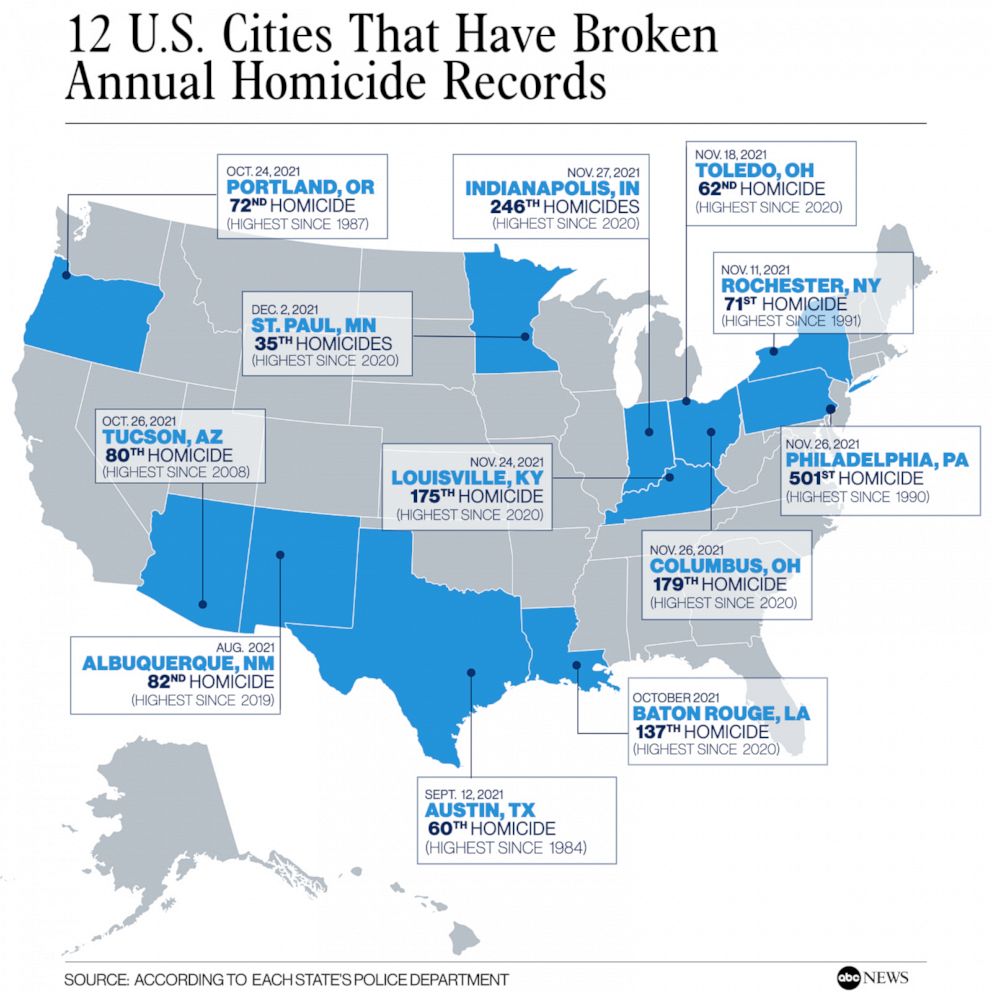

At least 12 major U.S. cities have broken annual homicide records in 2021 -- and there's still three weeks to go in the year.

Of the dozen cities that have already surpassed the grim milestones for killings, five topped records that were set or tied just last year.

"It's terrible to every morning get up and have to go look at the numbers and then look at the news and see the stories. It's just crazy. It's just crazy and this needs to stop," Philadelphia Mayor Jim Kenney said after his city surpassed its annual homicide record of 500, which stood since 1990.

Philadelphia, a city of roughly 1.5 million people, has had more homicides this year (521 as of Dec. 6) than the nation's two largest cities, New York (443 as of Dec. 5) and Los Angeles (352 as of Nov. 27). That's an increase of 13% from 2020, a year that nearly broke the 1990 record.

Chicago, the nation's third-largest city, leads the nation with 739 homicides as of the end of November, up 3% from 2020, according to Chicago Police Department crime data. Chicago's deadliest year remains 1970 when there were 974 homicides.

Philadelphia's homicide record was broken in the same week that Columbus, Indianapolis and Louisville eclipsed records for slayings.

Experts say there are a number of reasons possibly connected to the jump in homicides, including strained law enforcement staffing, a pronounced decline in arrests and continuing hardships from the pandemic, but that there is no clear answer across the board.

5 cities surpass records set in 2020

Other major cities that have surpassed yearly homicide records are St. Paul, Minnesota; Portland, Oregon; Tucson, Arizona; Toledo, Ohio; Baton Rouge, Louisiana; Austin, Texas; Rochester, New York; and Albuquerque, New Mexico, which broke its record back in August.

"The community has to get fed up," Capt. Frank Umbrino, of the Rochester Police Department, said at a news conference after the city of just over 200,000 people broke its 30-year-old record on Nov. 11. "We're extremely frustrated. It has to stop. I mean, it's worse than a war zone around here lately."

Indianapolis, Columbus, Louisville, Toledo and Baton Rouge broke records set in 2020, while St. Paul surpassed a record set in 1992.

Among the major cities on the brink of setting new homicide records are Milwaukee, which has 178 homicides, 12 short of a record set in 2020; and Minneapolis, which has 91 homicides, six shy of a record set in 1995.

According to the FBI's annual Uniform Crime Report released in September, the nation saw a 30% increase in murder in 2020, the largest single-year jump since the bureau began recording crime statistics 60 years ago.

'Nobody's getting arrested'

Robert Boyce, retired chief of detectives for the New York Police Department and an ABC News contributor, said that while there is no single reason for the jump in slayings, one national crime statistic stands out to him.

“Nobody’s getting arrested anymore," Boyce said. "People are getting picked up for gun possession and they're just let out over and over again."

The FBI crime data shows that the number of arrests nationwide plummeted 24% in 2020, from the more than 10 million arrests made in 2019. The number of 2020 arrests -- 7.63 million -- is the lowest in 25 years, according to the data. FBI crime data is not yet available for 2021.

Christopher Herrmann, an assistant professor in the Department of Law & Police Science at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City, said the decrease in arrests could be attributed to the large number of police officers who retired or resigned in 2020 and 2021.

A workforce survey released in June by the Police Executive Research Forum found the retirement rate in police departments nationwide jumped 45% over 2020 and 2021. And another 18% of officers resigned, the survey found, a development which coincided with nationwide social justice protests and calls to defund law enforcement agencies following the death of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police officers.

On average, the survey found that law enforcement agencies are currently filling only 93% of the authorized number of positions available and Herrmann said many departments have been hampered in hiring because of an inability to get large classes into police academies due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

"I think, unfortunately, police departments are just losing a lot of their best and experienced officers and then because of the economic crisis, because of COVID, are having difficulties in hiring or just delays in hirings," Herrmann said.

Herrmann said he suspects that a confluence of other factors has also contributed to the spike in lethal violence over the last two years. He said the COVID-19 pandemic not only prompted a shutdown of courts and reduction in jail population to slow the spread of the virus but also derailed after-school programs and violence disruption programs.

Confluence of factors

"I wish there was one good solid reason that I could give you for the increases, but the reality is there is none," Herrmann, a former crime analyst supervisor for the New York City Police Department, told ABC News.

Herrmann said he was surprised to see the number of homicides going up in major cities across the United States after an overall 30% jump last year.

“I knew 2020 was going to be a bad year because of the (COVID-19) pandemic but I really thought that a lot of these numbers would come down in 2021 just because a lot of society reopened and reopened pretty quickly," Herrmann said. “We don’t have the unemployment problem, we don’t have a lot of the economic stresses, housing and food insecurities aren't as much of an issue. A lot of those things were leading to the mental health stressors that were plaguing the country."

As part of a recent ABC News series "Rethinking Gun Violence," Dr. Daniel Webster, the director of the Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Policy and Research, said 2020 was the "perfect storm" of conditions where "everything bad happened at the same time -- you had the COVID outbreak, huge economic disruption, people were scared."

Webster added, "It's particularly challenging to know with certainty which of these things independently is associated with the increased violence. Rather it was the 'cascade' of events all unfolding in a similar time frame."

Chief LeRonne Armstrong of the Oakland, California, Police Department told ABC News recently that the lack of resources to fight crime is one of the reasons he suspects is why his city is seeing the highest number of homicides in decades. Oakland police have investigated at least 127 homicides in 2021, up from 102 in all of 2020. The Bay Area city's all-time high for homicides is 175 set in 1992.

Armstrong said his department's 676 officers is the smallest staff his agency has had in years, nearly 70 fewer officers than in 2020.

"To have 70, nearly 70 less officers a year later," Armstrong said, "is definitely going to have an impact on our ability to address public safety."