40 years after the Jonestown massacre: Jim Jones' surviving sons on what they think of their father, the Peoples Temple today

"There's somethings about Jonestown I'm never going to deal with."

It’s been 40 years since Peoples Temple leader Jim Jones led more than 900 of his followers to participate in the mass murder-suicide that would become the largest deliberate loss of American civilian life until Sept. 11, 2001.

Today, his sons, who survived the massacre because they happened to be away that day, say they are still trying to find healing and forgiveness for their father and themselves.

“There's some things about Jonestown I'm never going to deal with, and I'm okay with that,” Jim Jones, Jr., 57, said in an interview for “Truth and Lies: Jonestown - Paradise Lost.” “The mind's a dangerous neighborhood. Don't go alone.”

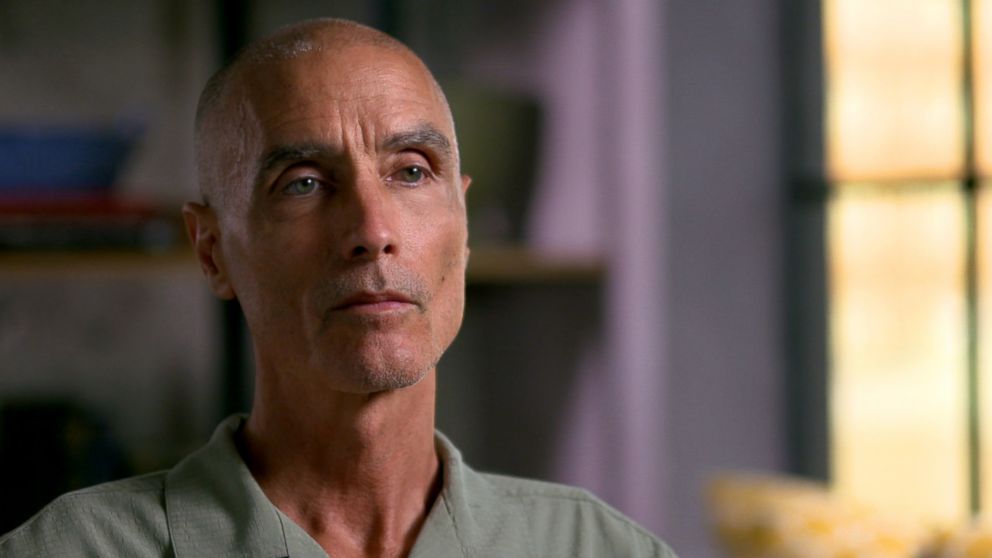

“There were many people that were dear to me and a good number of them that I was very dear to,” Stephan Jones, 59, said. “I often thought about what it must have been like for them for us not to be there, you know. And I ask their forgiveness.”

The Peoples Temple was a ministry of Jim Jones’ own devising. Jones convinced hundreds of his American followers to move to his compound, known as Jonestown, in the South American nation of Guyana. Of the 918 Americans who lost their lives in the Jonestown massacre on Nov. 18, 1978, investigators determined 907 died from ingesting poison, including nearly 300 children.

They used cyanide, and either injected it into people with syringes or mixed it with a powdered soft drink called Flavor Aid. Others were shot or stabbed that day. Jim Jones himself was found with a single bullet wound to the head.

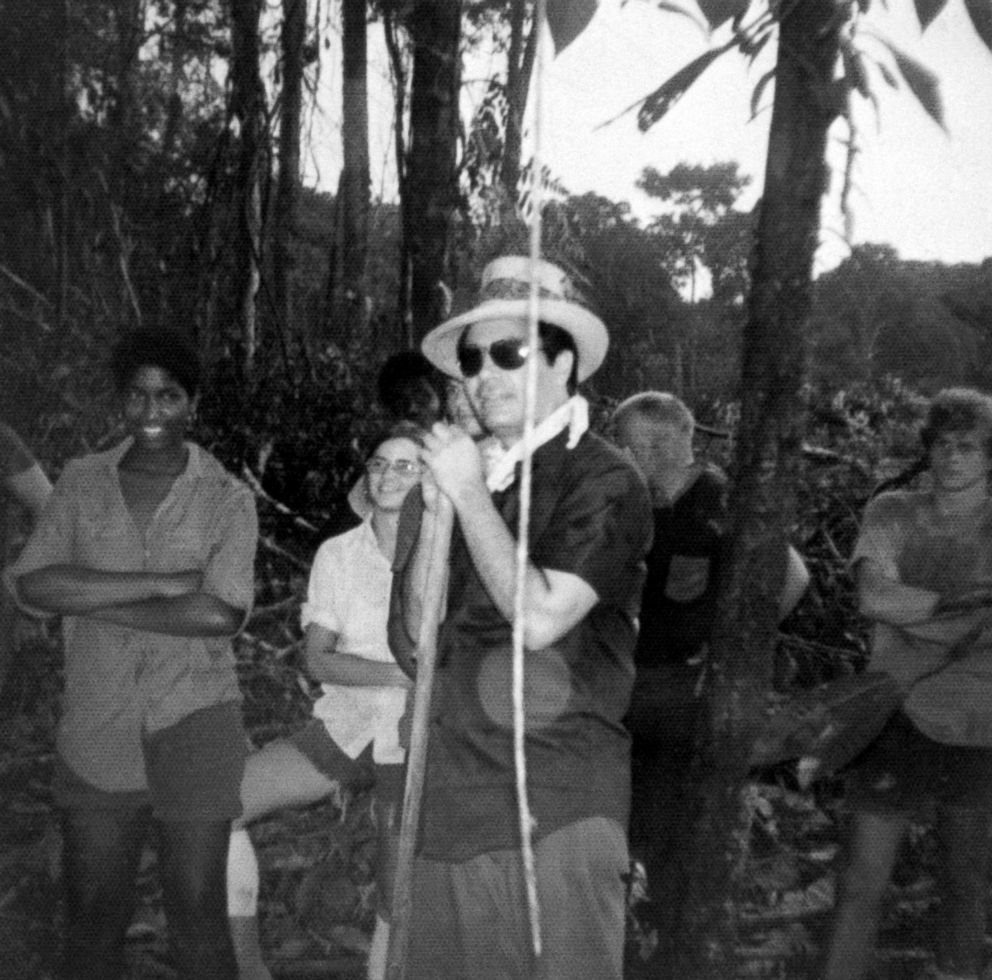

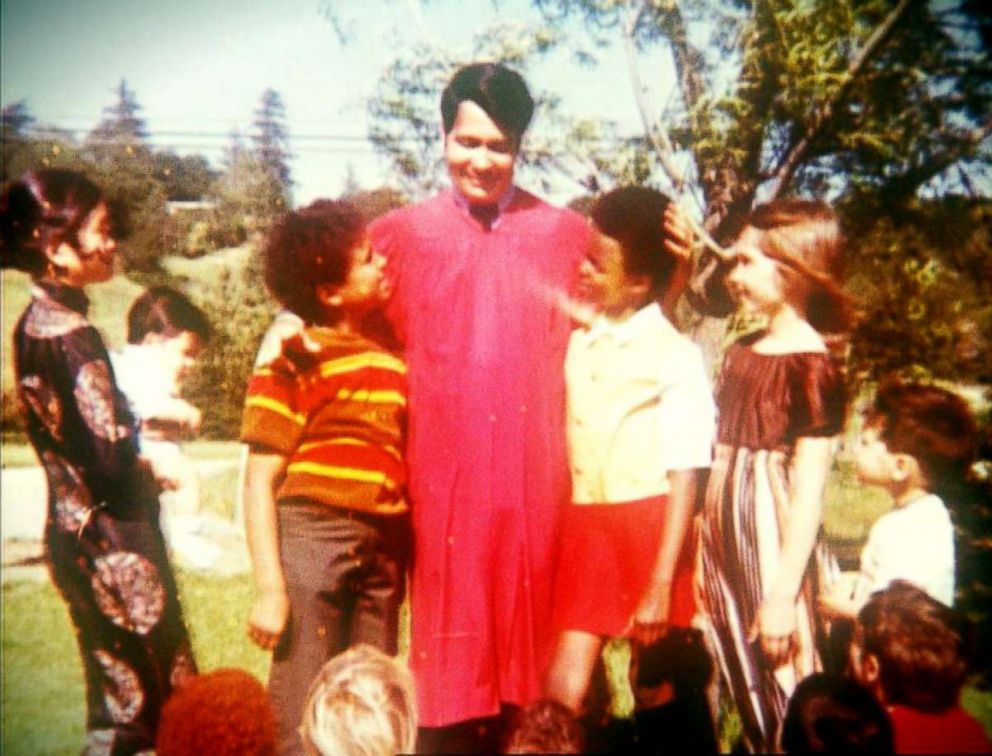

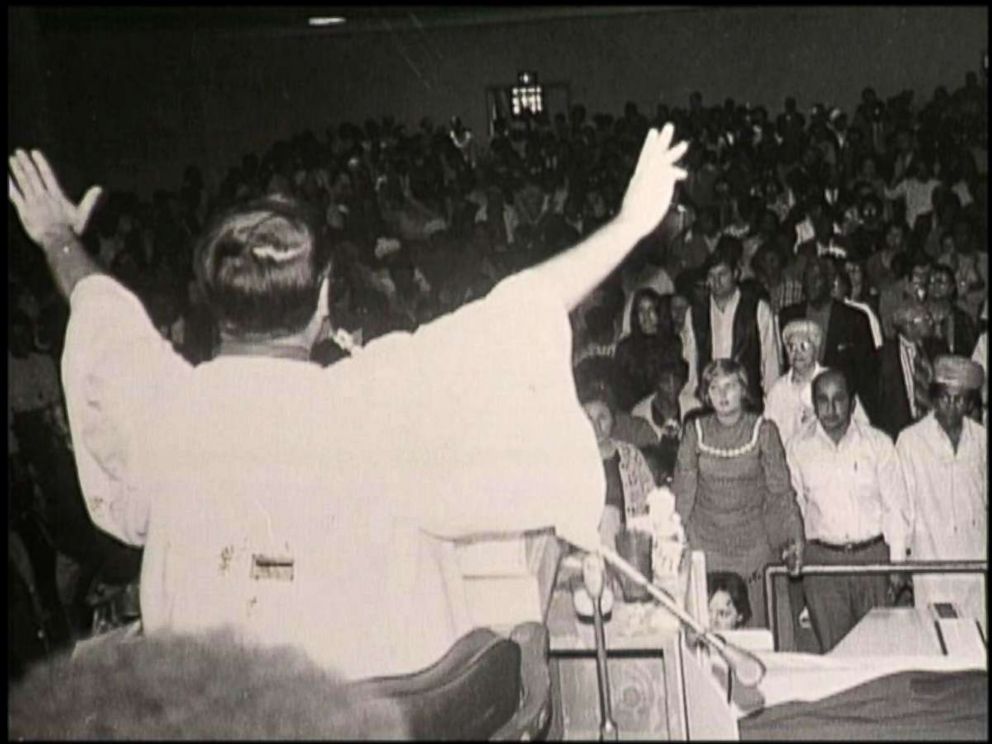

Jim Jones, who was white, founded his ministry, the Peoples Temple, in Indiana, where they promoted social justice, racial and class equality and desegregation.

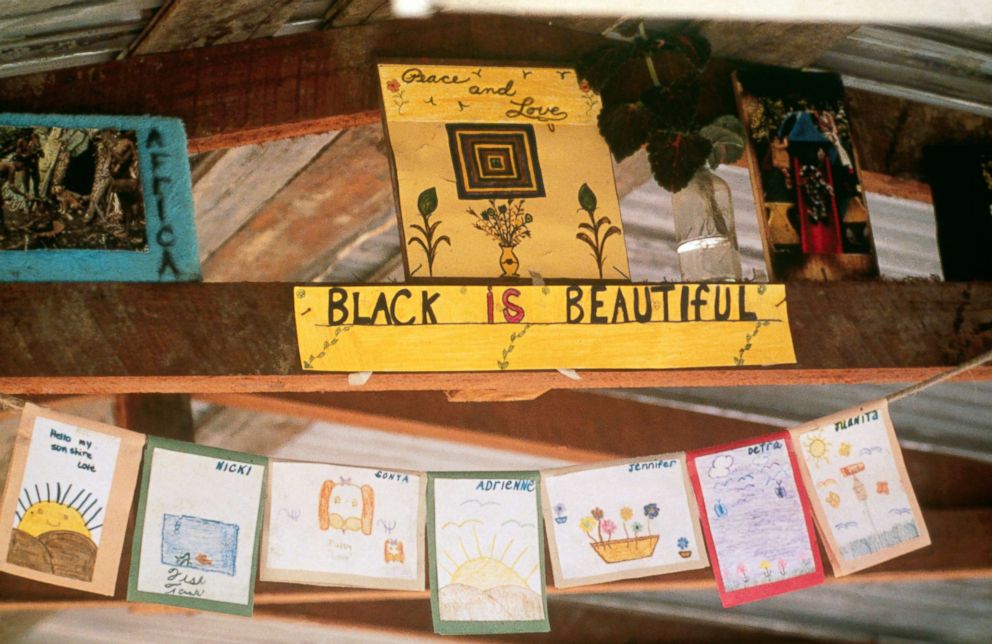

“I lived in a community that was filled with every walk of life, every color in the rainbow, every level of education. For the most part, we lived in harmony most of the time, especially early on,” Stephan said about his childhood. “It was not fake. I am so grateful for that because it showed me the truth of that, the beauty of that, the importance of that. So I loved that about him.”

Stephan said he believes his father’s primary purpose was to “bust down some walls and to create a community where all are welcome, no matter where they come from.”

But eventually, it became “all superficial,” Stephan said.

“There was nothing spiritual about my father. Of course, in my view of things, he had every bit the loved and juicy soul in him that everyone else does, but he had lost complete sight of that. His entire existence was superficial,” said Stephan.

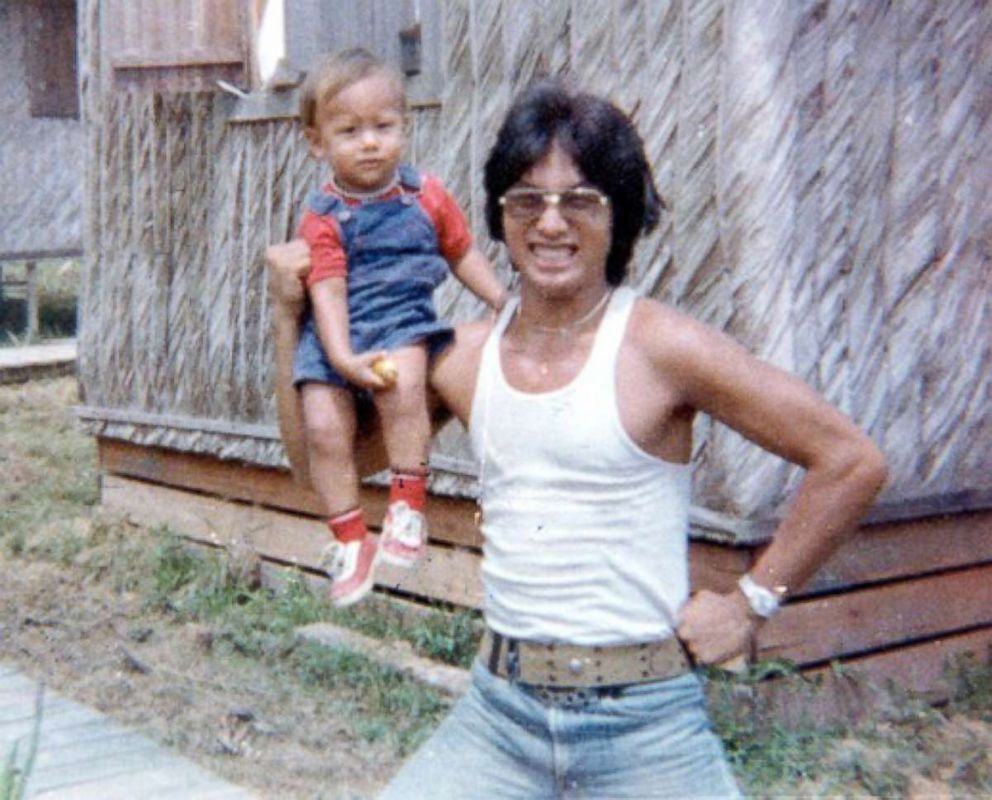

In addition to their biological son, Stephan, Jim Jones and his wife, Marceline, had adopted children of Korean-American, African-American and Native-American descent.

"They called themselves the 'Rainbow Family,' because they wish[ed] -- both in their church leadership life and in their personal life -- to show that all people are equal before God," said Jonestown scholar Mary Maaga.

Jim Jr., was their “black son.”

“Stephan and I are a paradox,” Jim Jr. said. “Stephan is a natural son, adopted into a family of very mixed races. He wasn't unique because he was a natural son. In some ways, people would say, I was more unique because I was the black son and given his name.”

“You need to understand that there are dynamics that exist that do not exist in normal families. I mean, there are already jealousies and rivalries, and all of that going on, but it is heightened in a family that's got that kind of diversity,” Stephan said of growing up with his diverse family. “I never felt that we were taught how to live within that, or that we were guided in how to be aware of and navigate the many [feelings] we're going to have.”

For Stephan and Jim Jr., life with their father was dominated by his role as head of the Peoples Temple, especially as the ministry grew and moved to California -- first to Redwood Valley, California, in the 1960s, then to San Francisco in the 1970s. By then, the congregation had swelled to roughly 5,000 members.

“Not only was Dad never around, but it felt like everybody else had Dad,” Stephan recalled. “We didn't have our father, and they were taking our father away from us, so there was that resentment as well. It was hard on the family.”

As Stephan and Jim Jr., got older, they each came to have a different perceptions of their father, who former members said grew to become more extreme, manipulating his congregants with blackmail and administering humiliating beatings to those who displeased him. Former members also said Jim Jones abused drugs and alcohol.

“My experience with my father was he was more an actor than genuine, almost always. He was always aware of eyes on him,” Stephan said. “Because all that mattered to my father was his perception of other people's perceptions of him.”

Whatever praise or adulation Jim Jones got, Stephan said, his father always needed even more, whether it was “genuinely by doing something that people appreciated” or by other tactics.

“My father could in an instant identify what was most important to you and probably what you were most afraid of. He could quickly convey that he was the one to protect you from what you were afraid of and to help you have whatever it is that you longed for,” said Stephan.

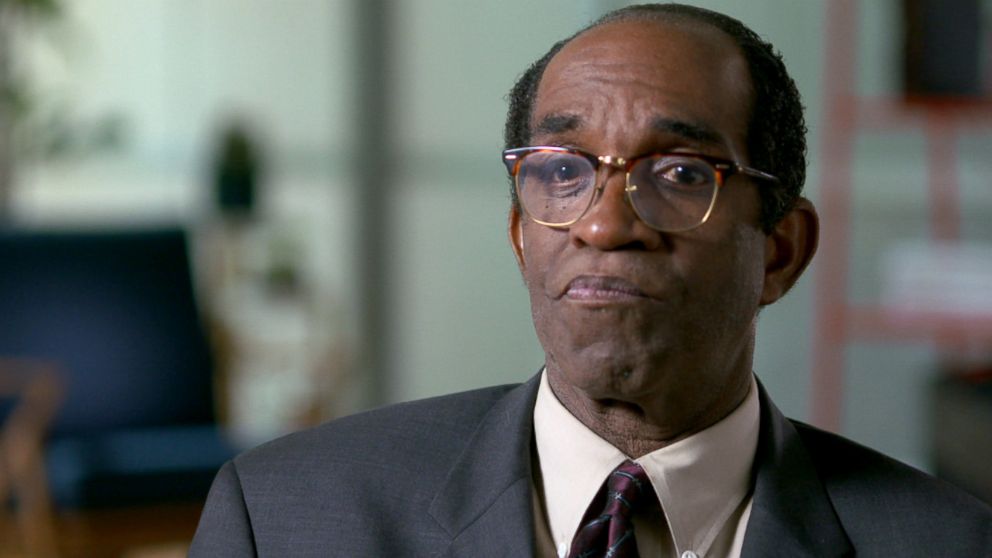

Jim Jr., says his view of his father was very different from his brother’s, who, Jim Jr. said, saw their father’s fraud immediately.

“I was a true believer. When I say true believer, I believed in all the things that Peoples Temple could have been,” Jim Jr., explained.

Unlike Stephan, Jim Jr., said his gratitude for being adopted into the family affected how he saw his father and his father’s mission.

“He saved me from all this, a fine education, a fine life. [I was] married to a beautiful woman getting ready to have a child. Stephan's paradigm was different,” Jim Jr., said. “He was born, and he looked at life and he listened to my father, listened to my mother, and he goes, ‘Why did you bring me into this world?’ I didn't have that choice. I was grateful that I was safe in the world that I was brought into.”

Stephan, on the other hand, said that though he wasn’t afraid of his father, he was afraid of what his father might do and of his message.

“Dad, like any good demagogue, would conjure up fear,” Stephan said. “What I'm hearing in the audience is all the gloom and doom: The pending nuclear war. ‘We're all going to be ushered into, or put into, concentration camps if we're not exterminated some other way. There are white racists around every corner that want to take us out.’ The immediate community that we were in, in Redwood Valley, they all hated us, as far as my father was concerned.”

Stephan said he thought his father was dangerous.

“His message was incredibly violent as time went on. And it was erratic,” Stephan said. “If we weren't having an open meeting where he was trying to bring in new members, we were having closed meetings where he was trying to control the members.”

Former members said Jim Jones began to practice "fake suicides" in small groups. "Dying for the cause" was something some former members said Jim Jones brought up regularly.

“The idea of giving my life, losing my life probably in a violent, horrible way, yeah, I was kind of afraid of that,” Stephan said. “I was afraid of what he might do, and what he said we had to do, and what he said would happen to us.”

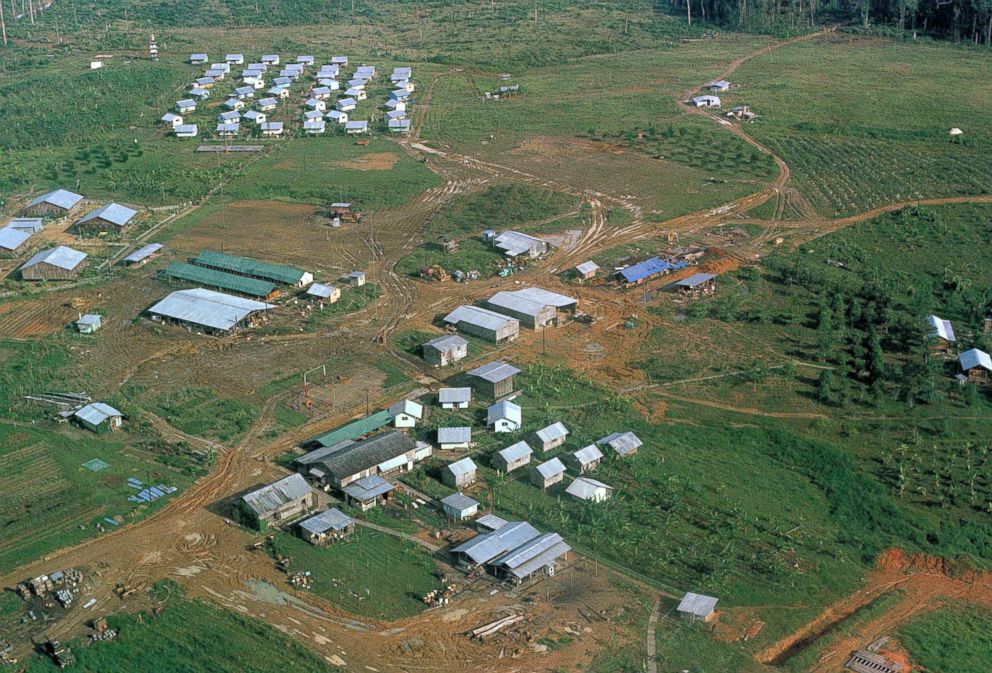

In 1974, Jones leased more than 3,800 acres of isolated land in the jungle from the Guyanese government. He believed that in this mostly English-speaking South American country, “Jonestown,” could become a sort of utopia for his California-based congregation.

Stephan was around 17 years old when he moved to Jonestown in February 1977 to help build the compound. Jim Jr., followed that July and was 16 years old at the time.

“My experience in Jonestown was this: when I first got there I was happy and I was really enjoying myself. I really was coming to understand what it meant to be a part of something bigger than me,” Stephan recalled. “We had a goal that was attainable, not grand. We're going to build a town for the people we love. Right? We're going to do it together, to the best of our ability.”

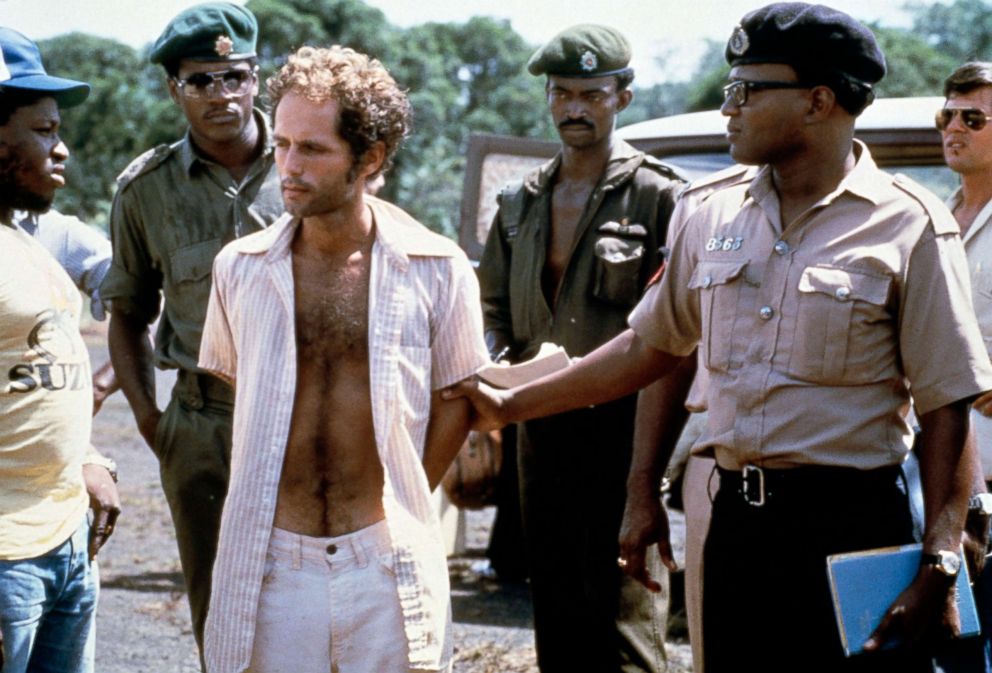

But on Nov. 18, 1978, tragedy struck with the massacre at Jonestown. On that day, Stephan and Jim. Jr, were away from the settlement with the Jonestown basketball team in the Guyanese capital of Georgetown, where they were set to play in a tournament.

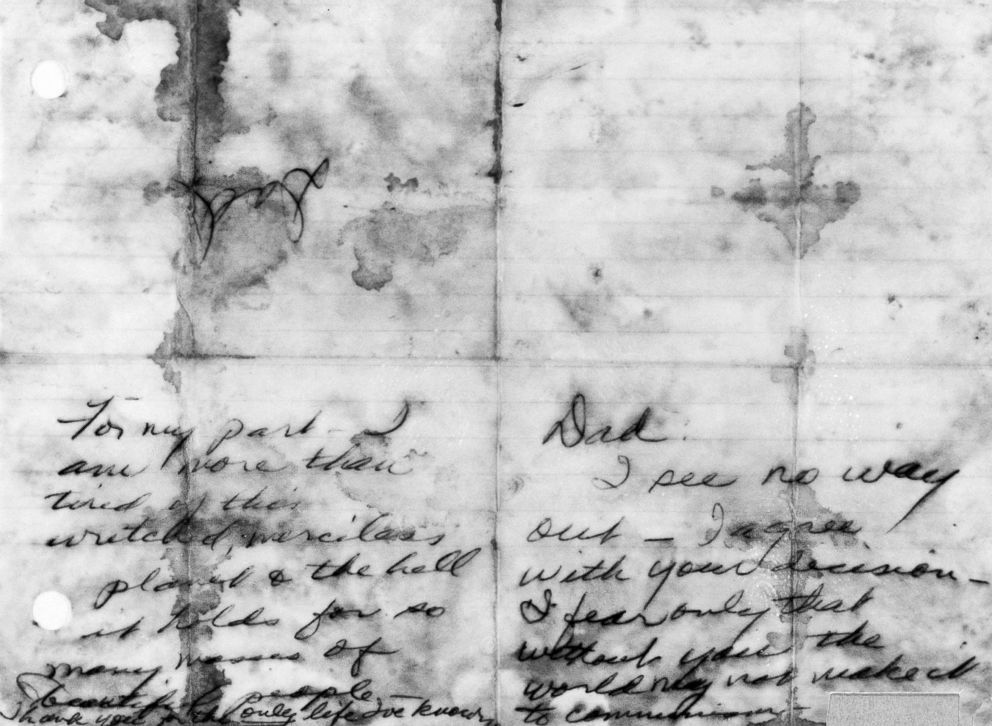

Most of the members of the team were spending the day off watching a movie, when Jim Jr., got a message from his father.

“November 18, when I received the call from my father and actually spoke to him, and he said we were going to visit Mr. Fraser. Now I was the director of communications on our security team, so I knew what that code meant, okay? That code meant revolutionary suicide,” Jim Jr. said. “My first reaction was, ‘There's got to be a different way. No, Dad, we've got to do something different.’ And he goes, ‘No, you need to be strong. You need to be our avenging angels.’”

Looking back at the Jonestown tragedy

In the time after, the team members frantically pleaded with authorities to get to Jonestown immediately. Jim Jr.’s wife and unborn child were among those who died at Jonestown.

“I've spent many years coming to terms with leaving that town at the time that we left it, and now having the wherewithal that we should have stayed. Hell, we were ordered back, and we refused to come back. That was partly because we were enjoying our freedom. We were enjoying the basketball. We were enjoying the camaraderie,” Stephan said.

“We were commiserating against my father. Every guy on the team now, we were all cracking jokes about him and temple life, something unheard of. That was intoxicating. But, we also really had convinced ourselves that this coward would never, ever take himself out,” Stephan added.

Stephan said there were times well before that final day that he and others could have put a stop to what was going on.

“There were many times that we probably could have steered things in a different direction. We could have put a stop to what happened long before that final night, and we didn't get it done,” Stephan said. “For me it was because I was too focused on myself and not enough on my community and what was best for them. In much more simpler terms, it's just that I wasn't there when they died. I don't know what I would have done or could have done.”

For Jim Jr., basketball was never the same.

“When people say basketball saved their life, I can literally say basketball did save my life,” Jim Jr., said.

Jim Jr., said he has wanted nothing to do with the game since that day.

“It wasn't until my oldest son wanted … me to teach him basketball,” Jim Jr., said, who has since remarried. “He had heard that I played basketball. That was hard because I had looked at basketball being the vehicle to where I survived and lost all my family. So I wanted nothing to do with that but when I saw him at 5 years old wanting to learn basketball ...”

Jim Jr.’s eldest son Rob was named San Francisco's "Player of the Year" when he was in high school and went on to play basketball in college.

“I was coaching at the place he played. It turned my life around,” Jim Jr. said. “It was for so long I was known as Jim Jones' son. And it wasn't until Rob started playing that I started being known as Rob's dad.”

Jim Jr. said that his sons are aware of who their grandfather was, and that he and his family are not ashamed of having the last name Jones.

“Depending on the day. Depending on my self-worth, depending on the blessings that I see in my life. Do I feel blessed that I was Jim Jones's son or do I feel cursed?” Jones said. “I'm proud to be Jim Jones Jr... I think that's my 40 year celebration of life, that it's not how you got to some place. It's how you move on."

For Stephan, he says he found his healing in trying to tell the stories of those who lived at Jonestown.

“I went into the California Historical Society, and I had been given a lot of photographs of the Temple from across many years and I spent hours and hours identifying every photo,” he said. “If there was even one person whose name I could not recall, I set that photo aside and I continued on and I'd do whatever I had to, to remember that one person. May seem like a small thing, you know given the devastation of Jonestown, but that's where I found my healing.”

Stephan says he’s forgiven his father. He has since written several essays about his father and the legacy of Jonestown.

“That was the only way I was going to make anything positive out of what happened there was for me to come to some kind of forgiveness,” Stephan said. “In that gratitude, I am free to now look forward.”

ABC News' Monica DelaRosa and Muriel Pearson contributed to this report