Afghanistan veterans, families in crisis after country’s shocking, rapid fall

The Department of Defense announced it will offer mental health resources.

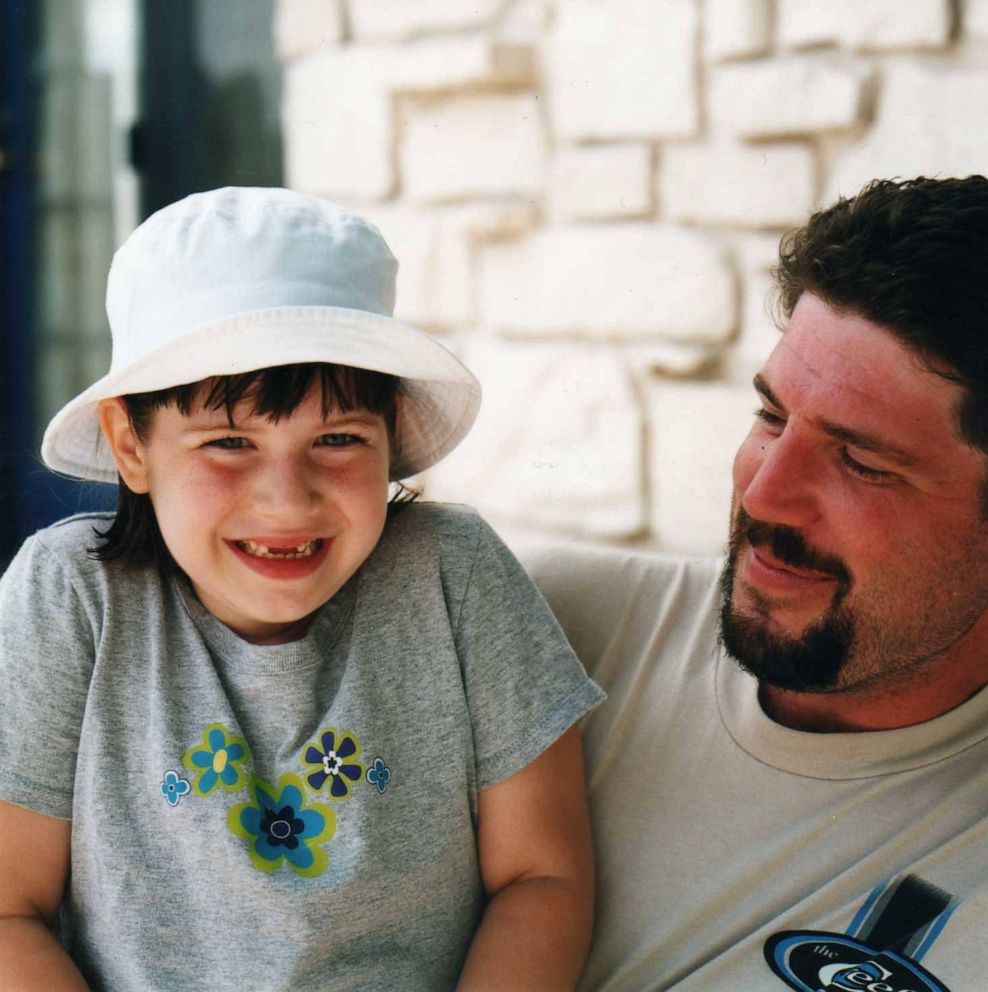

Kylie Willis’ family is one of over 2,000 families in the U.S. who have lost a loved one who served in the war in Afghanistan.

Now reeling from the rapid collapse of the Afghan government 20 years after the U.S. first invaded the country, the re-establishment of the Taliban has caused Willis to ask, “Why?”

“Why did I send my loved one to die for this country if things just went back to the same?” she told ABC News.

That question haunts many of the thousands of Afghanistan gold star families and veterans advocates worry the takeover may be triggering a mental health crisis among U.S. veterans.

Willis was 15 years old when she lost her father, who was killed in Afghanistan, Staff Sgt. Kirk Owens. He was driving on a notoriously dangerous road in 2011 when he was struck and killed by an improvised explosive device along with two other members of his unit in the Paktia province, an area that had seen increasing violence and fighting.

“He didn't ask anybody to do anything that he wouldn't do himself,” Willis said. “He took the front seat and the front car, because he knew it was the most dangerous. They're going down a dangerous path, and he took that spot so somebody else didn't have to.”

Jane Horton’s husband, Army Spc. Chris Horton was 26 years old when he was killed in Paktia just a month after Willis’ father.

“When I sent my husband to war, he was not my own. He was our country's,” Jane Horton said. “He was America's son, and so I think that ... he would not be happy. He would be very broken and very horrified.”

Horton has dedicated over 12,000 hours helping service members and their families since her husband’s death. Since the Taliban took the country, she says the “number one” thing she hears from other families is, “What did my loved one die for? It wasn’t for this.”

“My tears were not for this, and hopefully our country will show us that our loved ones’ sacrifice was not in vain,” she said.

Bryan Moore is a 23-year veteran of the Army who has completed seven tours in Afghanistan. He said he recently overheard a radio show host asking that same question: was his service in vain?

“That stung me. I mean, why would you even bring that up? Why would you start saying that?” he told ABC News. “That question has nothing to do with the soldiers [and] has everything to do with the leadership of our government and the choices that they're making. Not anything to do with the soldiers and their service.”

Moore, like many others, worries about the friends they made overseas.

“I met some Afghans that worked with the government. And one in particular, he was the nicest guy,” Moore said, adding they were reunited a year after not seeing him. “He remembered my name. It was it was great. He gave me a flag and. I still have it.”

Army Gen. Jack Hammond worries about the girls he helped build a school for in Kabul, while he was a commanding general there.

“We adopted an orphanage. We built an all-girls school or regular schools while we were working with Afghan security to transition security,” Hammond told ABC News. “You know, you go on your phone and you look at the old pictures and you see the beautiful little kids. Now, Lord knows what's going to happen to them.”

The Department of Defense announced that it will offer mental health resources to American service members and their families this week after the collapse in Afghanistan.

“Service is never for naught,” the statement read. “Remember that what is happening now does not minimize or negate the experiences of all who served overseas.”

U.S. Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin acknowledged these are “difficult days” for American veterans at a press briefing yesterday.

“Let me say to their families and loved ones, our hearts are with you. And the U.S. military stands as one to honor those we've lost,” he said.

Hammond is retired and now working at Home Base, a Boston-based organization that helps vets with what they call the “invisible wounds of war.”

“Those that were doing OK, they're not doing OK. And for those that were not doing OK, [they’re] doing a lot worse,” Hammond told ABC News.

“I'm talking to a lot of guys that weren't having any mental health issues that were doing really well, and for the first time ever, they now really are feeling it because they're all ripped up,” he added.”

Moore has had his own struggles with post-traumatic stress disorder, brought on by the residual trauama from his time deployed.

“This is going on and I am trained to do something about it, but there's nothing I can do right now,” Moore said.

He said he wants veterans and their families to know that they are not alone in their struggles.

“There's a whole group of people around the veteran that need help, too. So I think about those people, and it's just, everything now is intensified by the last few days,” he said. “Without the support of my family and my wife … I wouldn't be here today without them.”

Hammond urged veterans and their loved ones not to “suffer in silence.”

“If someone sees this,” Moore said, “and they're inspired by what I say and they go and they just talk to somebody about what they're feeling ... it makes a huge difference.”