What to know about Biden's other student loan repayment plan, to lower monthly payments based on income

The policy will have to make it through the regulatory process first.

Millions of federal student loan borrowers could soon pay less money back on their debt for a shorter amount of time, should a proposed Biden administration rule take effect later this year.

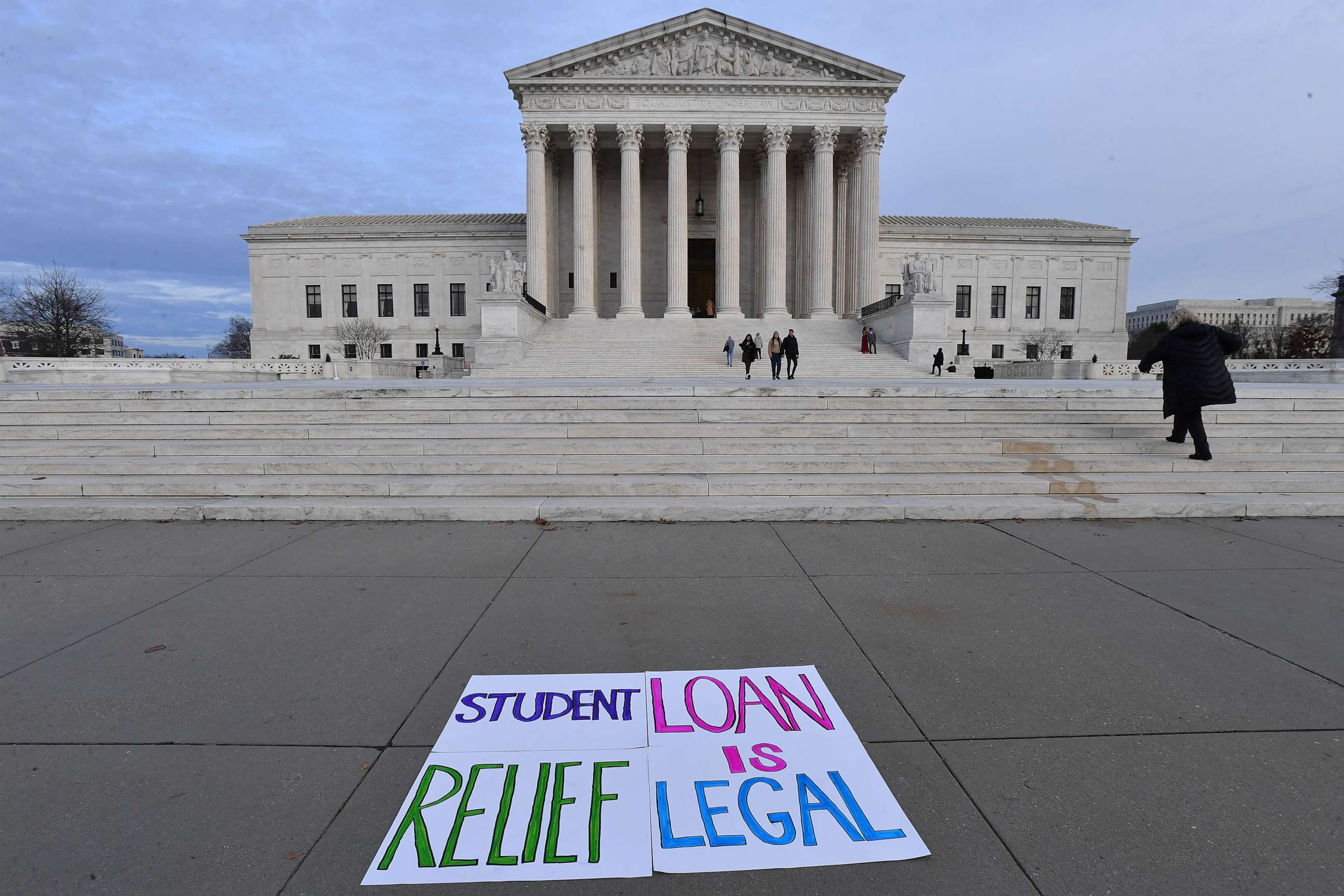

The new rule, which aims to revise the government's loan payment system in favor of borrowers, comes as the White House's broader, more well-known push to cancel millions of loans was struck down by the Supreme Court.

With that plan rejected, President Joe Biden's revisions to the repayment system, detailed in dense handouts and data-heavy bullet points from the administration, could become one of his most significant remaining avenues to reduce student borrower debt over criticisms from conservatives of a "giveaway."

The Department of Education began the regulatory process to bring the new loan repayment rule into effect more than a month ago, on Jan. 10 -- but the exact timing for when student borrowers could take advantage of the new payment plan remains unclear.

And while the plan was first announced last year alongside Biden's student debt cancellation policy back in August, the repayment changes are separate from that lawsuit and haven't seen any legal challenges so far.

What would the new plan do

The new plan would revise and expand the Revised Pay As You Earn (REPAYE) Plan, essentially aiming to make it the most common repayment plan for borrowers who qualify.

As one of the government's four current income-driven repayment plans, the REPAYE Plan ties the amount borrowers owe each month to the amount they make in income.

Roughly 8 million Americans are already enrolled in income-driven repayment plans and could feel the effects of the new change.

Under the new plan, the lowest-income borrowers would see their payments fall by about $0.83 per each dollar they owe, the Department of Education estimated, because they would be allowed to pay smaller minimum payments each month.

The highest-income borrowers would see their payments per dollar fall by about $0.05.

The changes would also exempt the lowest-income Americans from paying monthly minimums at all, stop unpaid monthly interest from accruing and allow debts to be forgiven sooner -- between 10 and 20 years after the loans were taken out.

The regulatory process could take any number of months, though it will likely not be finalized before springtime at the earliest, a source familiar with the discussions previously told ABC News. The application process would roll out after that.

Department of Education Undersecretary James Kvaal called the repayment changes the first "true student loan safety net in this country," while Education Secretary Miguel Cardona told reporters in January that the proposed rule is the most influential part of the Biden administration's plan to decrease federal student loan debt.

"Today, we're making a new promise to today's borrowers and to generations to come: Your student loan payments will be affordable, you won't be buried under an avalanche of student interest and you won't be saddled with a lifetime of debt," Cardona said on a call with reporters in January.

At their core, the revisions are intended to allow Americans to pay back less in loans over time, he said.

"It means money in the pockets of hard-working Americans," he said.

Exactly who do the income repayment changes impact and how?

The changes under the proposed rule to the REPAYE Plan would prevent single low-income Americans from having to make any monthly payments on their federal student loans if they make less than the annual equivalent of $15 an hour, which is around $30,600 a year.

For a married couple with two kids, that would rise to $62,400 a year.

"Workers getting by on $15 an hour often struggle to pay for their housing, food and other basic needs, let alone student loan payments," Kvaal said in January.

The changes would cut down the amount that borrowers have to make on their monthly payments by half -- from 10% of their discretionary income to 5%.

Those enrolled in the new REPAYE Plan would be shielded from unpaid interest accrual, one of the largest additional fees that borrowers face on their loans, because unpaid interest would be forgiven so long as qualified borrowers make their monthly payments on the loan itself -- even if their required payment is $0.

"As you make your payments, your balance won't grow. In other words, you won't go deeper into debt because interest is more than you can afford," Kvaal said in January.

The timeline for some debt forgiveness will also be shortened under the new plan, especially for community college students.

After 10 years, the new plan would relieve outstanding debts for people who took out less than $12,000 in loans initially -- commonly students who attend less expensive, shorter programs like community college.

The Department of Education has estimated that 85% of community college students would be debt-free within 10 years, if they enrolled in the new plan.

And, as is already the case under the current income-driven repayment programs, all borrowers with outstanding debt after 20 years of payments would have their debt canceled. (For graduate students, the timeline is slightly longer -- 25 years).

How much will the program cost?

The Department of Education estimated that the new REPAYE Plan would cost a net total of $137.9 billion over the next 10 years.

That cost increase comes after Congress has already decided to keep the budget flat for the Office of Federal Student Aid during the upcoming year -- potentially putting programs on thin ice.

Asked if the Department of Education could still afford the reforms to the plan, a senior administration official said last month that they were still working through the "full impact" but that it was their goal.

"It's true that we were very disappointed with the level of funding we received from Congress for Federal Student Aid, and that's going to make it a challenge for us to carry out a number of our policy initiatives," the senior administration official said.

"We're currently working through the full impact of the funding level that we received from Congress. And again, our goal is to implement this IDR plan in 2023," the official said.

Critics of the new plan argue that it could cost even more if it incentivizes more people to take out student loans by changing the rules in borrowers' favor.

"The changes mean that most undergraduate borrowers will expect to only repay a fraction of the amount they borrow, turning student loans partially into grants," Adam Looney, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, wrote in September, when the plan was first announced.

"It's a plan to reduce the cost of college, not by reducing tuition paid, but by offering students loans and then allowing them not to pay them back," he said then.

But a senior administration official pushed back on that criticism.

"Almost every time there is a change in student loans to make the terms more generous for students, people talk about moral hazards and potential abuse of the program and there's just, you know, there's just no evidence that those predictions have ever come to pass," the official said in January.

The Education Department is attempting to change the repayment system because Americans are taking on higher debts than ever before, the official said.

"And the result has been that student debt makes it difficult, even for college graduates, to climb into the middle class, buy a home, start a family, and that many students are left worse off because of their student debt than if they had never gone to college at all," the official said.

"So our goals are to address those challenges, which are very real."