Black farmers fight to keep their land, cultivate next generation

“It’s about fairness,” John Boyd Jr., a farmer and fierce advocate, said.

John Boyd Jr., a fourth-generation farmer, grew up close to his 1,000-acre farm in southern Virginia where he now grows soybeans, wheat and livestock.

Juneteenth: Together We Triumph

A celebration in observance of Juneteenth, including an interview with former President Obama who talks about race, resilience and healing the racial divide.

Boyd, of Baskerville, Virginia, is also the founder of the non-profit National Black Farmers Association, which educates and advocates for Black farmers’ civil rights, land retention and access to public and private loans, among other initiatives.

Boyd and his father farmed together for 30 years and his grandparents were sharecroppers after the abolition of slavery in 1865.

“I know there were slaves and sharecroppers that helped build these barns here,” Boyd told ABC News. “You can see the logs were hand-carved by wooden axes. … Just looking at that reminds me of history, where I came from and where we have to go in this country.”

As part of his efforts with the NBFA, Boyd has worked to attract more Black people who are interested in farming, as well as to protect their rights and their land, even riding a mule-drawn wagon and driving a tractor to Washington, D.C., to lobby Congress.

“The most powerful tool you can possess, only secondary to Jesus Christ, is land ownership,” he said.

To be a farmer in the U.S. is to be part of an aging but crucial industry. Black farmers, especially, have seen their numbers plummet from nearly 1 million at the turn of the 20th century to only about 50,000 today, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. While the reasons are complex, they ultimately come down to economics, migration -- mainly to northern urban areas -- and discrimination and racism, according to the Duke Sanford World Food Policy Center.

In 2017, Black farmers were older than the overall population of U.S. farmers, according to the 2017 agricultural census, which said that their farms were smaller and the value of their agricultural sales were less than 1% of the U.S. total. Due to more complete data collection, the census found that the number of Black producers was 5% higher than in 2012, but the number of Black-operated farms dropped by 3%. In all, 57% of Black-operated farms had sales and government payments of less than $5,000 per year, according to the census, while 7% percent had sales and payments of $50,000 or more when compared with 25% of all farms.

A rich history of farming

Black people have a rich history in farming predating slavery. Leah Penniman, co-director of Soul Fire Farm in Petersburg, New York, said that the Mende and Wolof people of West Africa were expert rice farmers kidnapped from their homes and taken to the Carolinas.

“Our ancestral grandmothers had the courageous audacity to braid seeds into their hair,” Penniman told ABC News, adding that they were transported in slave ships with okra, cowpea, egusi melon, sorghum, millet and eggplant seeds.

Hundreds of years later, when enslaved people were given freedom, they were also promised no more than 40 acres of Confederate land along the Atlantic coast, a plan from the federal government that came to be known widely by the phrase “40 acres and a mule.”

The government’s promise was broken soon after President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, when his successor, Andrew Johnson, overturned the order and the land was given back to its original owners.

“If ‘40 acres and a mule’ had been a promise kept, that [land] would be worth almost $7 trillion today,” Penniman said.

Many of the former slaves became sharecroppers, often renting land from their former owners.

“It didn’t just stop when we were freed,” said Boyd. “Where were we free to go? We didn’t have any money. We didn’t have any resources. So, many Blacks stayed on these farms like my forefathers. … That’s how Blacks got land in the first place.”

'It's about fairness'

Boyd said the challenge for Black farmers has been holding onto the land and believes the federal government has failed to adequately support farmers of color.

“The last plantation,” as he calls the USDA, is “the very agency that’s supposed to be lending me a hand up, [and it is] the very agency putting Black farmers out of business.”

Boyd said that even up until the 1980s, he would see the word “negro” on USDA applications and that at his area’s USDA office, the only day they would see Black farmers was on Wednesdays.

“We named it Black Wednesday,” he said.

The USDA said in a statement to ABC News that it did include the word "negro" on the application Boyd referenced until at least 1988 and that it used the terms "Black" or "African American" since then. It also said the "scenario" Boyd recalled with regard to Wednesdays "is a reprehensible one, but we have no information to support the claim."

"It is clear that for much of the history of the USDA, Black, Hispanic, Native American, Asian American and other minority farmers have faced discrimination -- sometimes overt and sometimes through deeply embedded rules and policies -- that have prevented them from achieving as much as their counterparts who do not face these documented acts of discrimination," the USDA said in its statement. "We are committed to building a different USDA, one that is committed to equality and justice, celebrates diversity and is inclusive of all customers."

Boyd said that since 1995, “a half-trillion dollars -- with a ‘T’ -- have been paid out to large-scale farmers in this country in the form of just subsidies” by the USDA.

"That doesn’t include farm ownership loans, farm equipment loans, any of those things, and little to none has went to Black farmers," he said.

In 1999, the USDA settled the class action lawsuit Pigford v. Glickman, and eventually paid more than $1 billion to Black farmers, who claimed they were unfairly denied loans and other government assistance.

“It’s about fairness,” Boyd said. “It’s about dignity and respect.”

Signs of turning tide

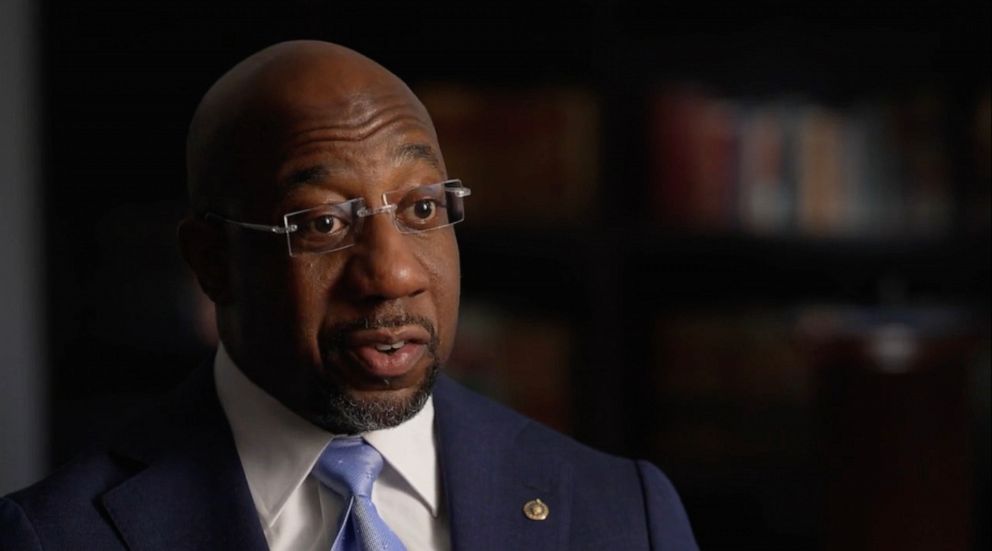

For Black farmers, the tide is showing signs of turning. In March, President Joe Biden signed the American Rescue Plan Act, a nearly $2 trillion law that directed $5 billion to farmers of color. Georgia Sen. Raphael Warnock, a Democrat, co-sponsored the bill, which is meant to provide additional relief to Americans impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The COVID-19 pandemic both illuminated and exacerbated long-standing health disparities and economic disparities,” Warnock told ABC News.

Lestor Bonner, a Vietnam War veteran and fifth-generation farm owner, said that in 1893, his great-grandfather bought the farm that he now works on. He said there’s only 136 acres left and that he needs $20,000 to save it from foreclosure. The relief money, he said, could help jumpstart his business after a difficult year living through the COVID-19 pandemic.

Bonner said he thought he would have the money by now “so I could get a crop in the ground this year,” he told ABC News.

As part of the American Rescue Plan Act, the USDA had set up a loan forgiveness program that would have helped Bonner pay off his outstanding loans, as well as pay for supplies and equipment to help him continue farming. But this month, a federal judge in Wisconsin ordered the government agency to stop forgiving loans, saying the program unconstitutionally uses race as a factor in determining who is eligible.

Penniman says her organization’s mission is to help Black farmers hold onto their land, as well as to introduce young Black potential farmers to the occupation (the average age of Black farmers is over 60).

“We have between one and 2,000 folks who come through for these courses every single year at the farm to learn everything from taking care of the soil to planting a seed,” she said.

Penniman said that many important agricultural techniques, including many of the practices in organic farming, like raised beds, composting and cover-cropping “come out of an Afro-indigenous tradition.”

Boyd, for his part, said he’s “proud and excited to see young people” taking an interest in land ownership and farming.

“There’s a new generation of Black farmers. I love that win,” he said. “So, I welcome them to the fight and welcome them as farmers and stewards of the land and contributors to agriculture and the fruit base in this country. That’s what my fight is all about.”