Boston Bombing Day 1: The Stunning Stop the Killers Made After the Attack

Just minutes after killing 3, Boston bombers went to the market.

— -- [This is the first of five installments of an ABC News digital special report '5 Days', which tells the hour-by-hour, day-by-day story of the investigation into the 2013 Boston Marathon bombing, with behind-the-scenes details based on interviews and evidence gathered by the FBI and Boston law enforcement agents who worked the investigation. Click to see Day 2, Day 3, Day 4 and Day 5. '5 Days' is written by Brian Ross and reported by Brian Ross, Rhonda Schwartz, Michele McPhee, Megan Christie, Randy Kreider and Lee Ferran.]

The challenge was to act normally. As if nothing had happened.

Go inside the store. Buy the milk. Get back in the car. Then head home.

The young man studied the plastic milk cartons in the dairy aisle at the huge Whole Foods store in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

It was 3:12 p.m. on Monday, April 15, 2013. Less than half hour earlier, twin bombs tore through the finish line of the Boston Marathon, creating a deadly scene of chaos and carnage.

But inside the store, all seemed normal. He finally grabbed one of the containers, walked over to the check-out counter and headed back to the parking lot.

He needed the milk for his 2-year-old niece. His brother was there waiting in the car. But when the young man with the milk approached the car, he was waved off and told to go back into the store -- he bought the wrong kind. The young man ran back inside, told the cashier he was going to exchange his carton of milk, and headed back out to the car.

The two brothers pulled out of the parking lot and headed home, with the quart of milk and a dark, ugly secret that made them proud.

Tamerlan and Dzhokhar Tsarnaev were the two terrorists who had detonated a pair of bombs at the Boston Marathon, killing three and injuring more than 260 others.

They were about to become the most wanted men in the world -- hiding in plain sight, preparing for another attack. The FBI would launch the biggest investigation since the 9/11 attacks.

Thousands of federal agents and police across the U.S. and around the world would employ every investigative technique they had to identify who had set off the bombs, to locate the brothers and stop them before they could kill again. Hundreds of videos and thousands of still pictures would be pored over, victims and witnesses interviewed, telephone records analyzed and more than a dozen possible suspects put under 24-hour aerial and ground surveillance. None of them would turn out to be the actual bombers.

Over the next five days, a number of innocent people would be wrongly accused by amateur sleuths, the FBI’s new, $1 billion facial recognition software would fail, the entire Boston metropolitan area would be put on lockdown based on bogus information and there would be more death and injuries -- more terror -- before the two brothers would no longer pose a threat.

But for 102 hours, that outcome was far from certain.

Day 1: The Marathon

The Fourth of July had been the original target date.

But Tamerlan Tsarnaev, 26, and his younger brother Dzhokhar, 19, discovered it was much easier than they had first thought it would be to build the bombs, and in the last few days they had decided the marathon would be their target.

The race was the pride of Boston -- the world’s oldest annual marathon, a symbol of community in a place that had been the birthplace of the American Revolution.

Hundreds of thousands of people, many waving American flags and some wearing tri-cornered Minutemen hats, gathered all along the course. It was a day to honor the country’s values.

It was everything that the Tsarnaev brothers, sons of Muslim refugees from Kyrgyzstan, had come to hate about America. The online videos they increasingly watched featured lectures about the Muslim children killed by U.S. soldiers and drones.

The actual decision to build the bombs had come at least five months earlier, in December 2012, when Tamerlan started to buy the components, according to court documents and officials involved in the investigation. Every few weeks he added another piece, following a recipe published by al Qaeda in its online magazine called Inspire. Tamerlan downloaded the article with its easy-to-follow instructions to “Make a bomb in the kitchen of your mom,” using common pressure cookers.

In February, following the recipe, he bought 48 "mortar shells" at Phantom Fireworks in Seabrook, New Hampshire, according to the documents. The gunpowder from the fireworks would give his bombs their punch.

Over the weeks Tamerlan also acquired several pressure cookers, two of which were used to house the explosives on April 15.

To trigger the bomb, he went to a hobby shop and bought two remote-control devices for toy cars -- one for each bomb -- as had been demonstrated on an online video he downloaded. The wires were attached to a Christmas tree light, shattered so its filament would be exposed and serve as the spark for the explosion.

Authorities would later say the brothers made at least seven bombs, some of those smaller pipe bombs. But the two biggest devices were made out of the six-quart pressure cookers, packed with gun powder and ball bearings.

All they needed then was something in which to hide the makeshift bombs. The day before the race, on April 14, Tamerlan went to a nearby Target store and bought two large, black backpacks.

The two brothers left the family apartment on Norfolk Street in Cambridge and drove across the Charles River to Boston, parking a few blocks away from Boylston Street.

'It Was a Beautiful Day'

The Richards family had made it a family tradition to join the crowds and watch the Boston Marathon every year. This year they went to their usual vantage point, just off Boylston Street.

But after a short while they left that location to take the children to Ben and Jerry’s on Newbury Street for ice cream. Bill Richard and his wife took bites from the children’s cones, and he can still remember precisely which flavors each of his children chose.

“It was a beautiful day,” he later recalled.

Afterwards, Bill and Denise decided to fight the crowds and find a spot near the finish line on Boylston Street, something they had never done when the children were younger.

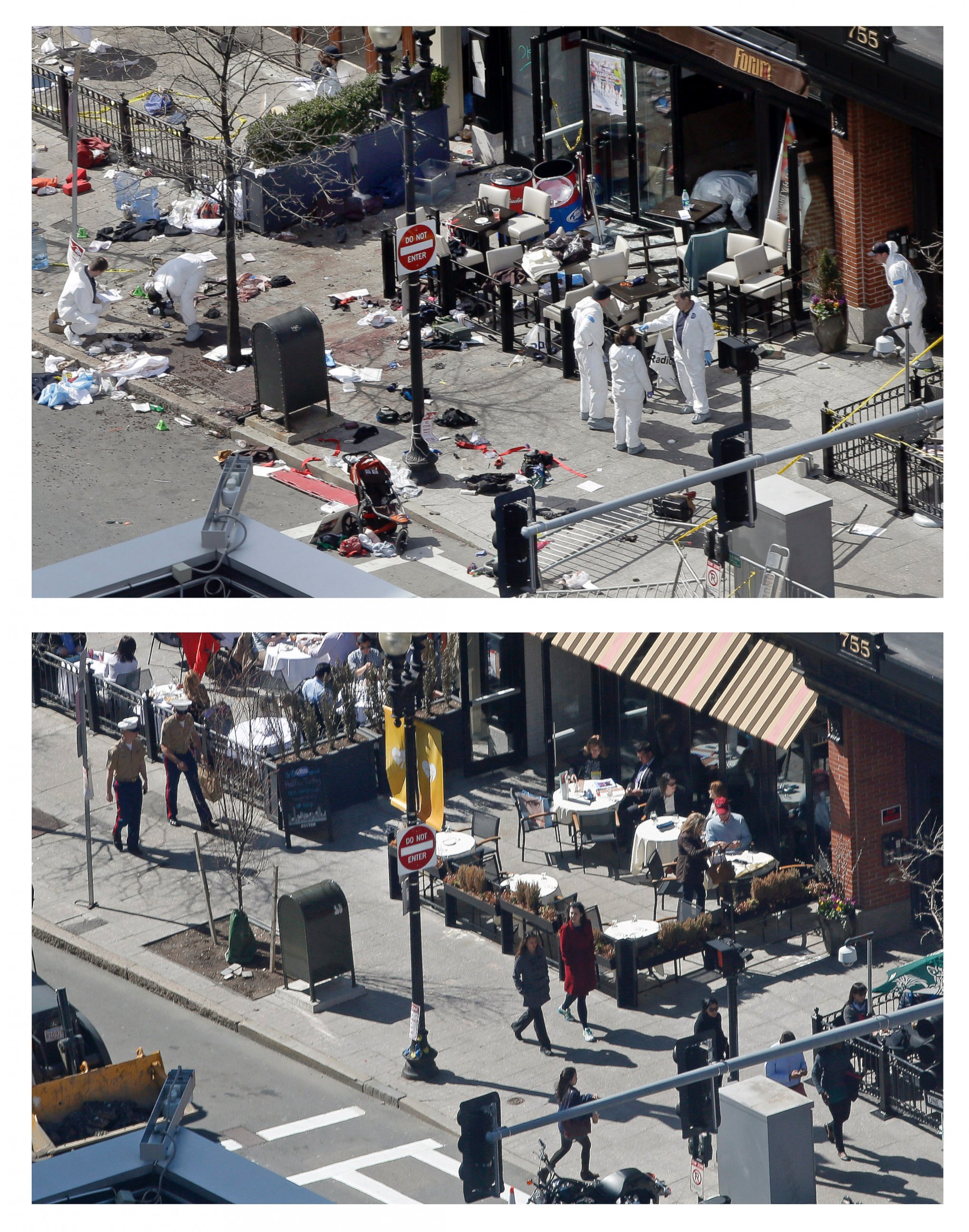

They stopped in front of the Forum restaurant, and found a place right in front, next to the metal crowd barriers, hoping to catch sight of the children’s coaches who were running the race.

“There was just an opening, so we took it,” Richard would later recall with deep regret. “It was very random.”

The Richards family had no idea that just minutes earlier two young men carrying bombs had come off a side street onto Boylston, rounding the corner at a bar called Whiskey’s, and began to head toward the finish line.

Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, wearing jeans and a white baseball cap he put on backward, stopped in front of the Forum restaurant right behind the Richards. Dzhokhar slightly dipped his shoulder to let his backpack carefully slide off his shoulder and slowly drop to the ground.

Bill Richard never noticed the young man with the white baseball cap or the backpack he put on the ground just behind them.

No one seemed to notice.

Meanwhile, Tamerlan Tsarnaev, 27, wearing a black baseball cap, kept moving -- about 600 feet down Boylston Street closer to the finish line.

He stopped in front of the Marathon Sports store, where he put his backpack on the ground as near to the street as he could get. As he did so, he bumped into Jeff Bauman, 27, who was at the finish line to cheer on his fiancée, Erin Hurley, as she completed her first marathon ever.

“He nudged me and I looked back at him and he looked back at me,” Bauman recalled, “And he looked suspicious. He was alone. He wasn’t watching the race. He didn’t look like he was having fun like everybody else.”

Then Bauman saw that the man had left his backpack behind.

“I just thought it was weird,” he said. “When you’re at the airport and see any unattended luggage, you tell the authorities. I was playing it off in my head. ‘You’re at the marathon, you don’t think of it. You’re in Boston. Stuff like this doesn’t happen.’”

Bauman thought about moving but his fiancée would soon be coming across the finish line and so he focused now on looking for her.

For three minutes the two brothers were just spectators.

Waiting.

And then Dzhokhar sent a text and made a 19-second call to his brother.

It was 2:49 p.m.

'Our Worst Fears Had Come True'

When the bombs went off, the Superintendent of the Boston Police Department had just finished the marathon himself.

As was his tradition, William B. Evans headed to the Boston Athletic Club to soak his aching muscles along with other cops who also ran the course. He joked that his office at headquarters was covered with framed metals from all of his races – a stark contrast to his predecessors who pinned menus from their favorite restaurants to the walls.

Evans had convened a meeting of the local, state and federal law enforcement officials who would be responsible for security at the marathon five days earlier.

Everyone agreed: the security threat was low. The Boston Marathon was considered an unlikely al Qaeda target. He said the only concern raised that day in the Boston police headquarters conference room was whether any of the activists from Occupy Boston or Anonymous might try to run onto the course near the finish line.

Extra uniformed police offices were assigned to line both sides of Boylston Avenue in front of the metal crowd barriers to make sure there was no such disruption. The extra police would be withdrawn after the first wave of elite runners crossed the line.

Confident that the threat was minimal and security in good hands, then-Superintendent Evans, known as Billy to his officers and friends from Boston’s South End, saw no reason he should not once again run the Boston Marathon course. For Evans, 47, this was his 44th marathon race.

That Monday afternoon, Evans said he was soaking in the hot tub when one of his officers rushed in the room.

“Superintendent,” the officer said, “I think two bombs just went off in Copley Square.”

Evans said at first he couldn’t believe it.

“That can’t happen here... It can’t be bombs. It’s got to be transformers or something, a gas explosion,” he recalled to ABC News.

But by the time he approached the scene, where he saw “fear in people’s faces, people crying,” he said he realized that “our worst fears had come true here, in the city of Boston.”

This was Evans' city. His friends. His race. He was not thrilled that the FBI had taken jurisdiction of the attack. But he pledged his full support to the FBI bosses, even as old rivalries and jealousies between the “locals and the feds” were hardly forgotten.

For most of the day, the FBI worked on the theory that the bomber or bombers might be among those injured and agents were stationed at the area hospitals to keep order, but also to make sure none of the injured could leave.

Managing a crisis requires communication and for hours the FBI cell phones did not work because so many in Boston were trying to call loved ones.

To make matters worse, the FBI makeshift forward command center in a ballroom of the Westin Hotel had only one hard-wire phone, which FBI Special Agent in Charge Rick DesLauriers commandeered so he could talk to Washington.

“This is mine,” he shouted as others tried to steal it away to call their own bosses.

Hundreds of FBI agents from around the country were sent into the city. For the first few hours there was no effective way to reach them or hand out assignments, nor was there any place for them to sleep.

Many simply slept in their cars in the FBI garage. Several agents ended up in the hospital from exhaustion, including the FBI official designated to handle crisis situations in Boston.

Agents worried there were more bombs in the hundreds of backpacks and purses left behind as spectators ran for cover so each and every piece had to first be examined by a bomb squad before being collected. The FBI immediately created a giant evidence processing center at a warehouse on Boston Harbor, called Black Falcon.

The crime scene was divided into hundreds of grids and every tiny piece of evidence was recorded with a GPS device to show precisely where it was recovered, according to agents involved in the investigation.

Twice a day, FBI airplanes flew pieces of evidence to the FBI crime laboratory in Quantico, Virginia.

First Key Clues: Bomb Fragments, Surveillance Images

Within hours, agents had a vital piece of evidence: the bottom of one of the pressure cookers converted into a lethal bomb. It was found on the roof of a hotel on the race route, blasted 100 feet in the air by the power of the bomb. Stamped into the piece was the name of the Fagor Company, the European company that manufactured the pressure cooker.

A squad of FBI agents was assigned to do nothing else but track every single pressure cooker shipped by the European company, which would eventually lead them to purchases made in the Boston area.

As investigators raced to trace clues in the bomb’s history, a large team of agents worked from the other end, searching through several hundred videos and photos that were sent to the FBI from spectators for any indication as to who carried out the attack. The biggest break came when FBI agents retrieved the surveillance cameras of the Forum restaurant which clearly showed the second blast.

But the day ended in disappointment because, even after dozens of agents and technicians had watched the tape over and over after it arrived around 6 p.m., no one could figure out who had placed the bomb in front of the restaurant. The crowd was just too big and lots of people walked through the crowded scene, many of them carrying backpacks with a change of clothes for friends or relatives who ran the race.

“We couldn’t see anything that stuck out,” said Kevin Swindon, Supervisory Special Agent at the FBI's Boston office. Swindon was the head of the division's Computer Analysis Response Team (CART) tasked with analyzing the incoming images.

“It was very frustrating because we watched it. We had numerous amounts of employees watching this video over and over and over again," he told ABC News.

They were up all night looking at the video again and again but no one -- no one in Boston or at the FBI lab in Quantico -- was able to spot the bomber that Monday night.

The Tsarnaev brothers watched the news at home that night, Tamerlan laughing when he saw an elderly runner fall to the ground after the first blast, according to a friend who spoke to investigators.

They had dinner with the friend and told him that America “got what it deserved.” The older brother told the friend, “So what if a kid dies? God will take care of him.”

Later the younger Tsarnaev posted on Twitter, “Ain’t no love in the heart of the city, stay safe people.”

'Five Days': Research by Alex Hosenball, Cho Park, Zoe Lake and Michael Birnkrant. Video editing by Shilpi Gupta, Abhinav Bhat, and Karl Dawson.

Get real-time updates as this story unfolds. To start, just "star" this story in ABC News' phone app. Download ABC News for iPhone here or ABC News for Android here.