BTK serial killer's daughter: 'We were living our normal life. ... Then everything upended on us'

In a new book, Kerri Rawson describes her relationship with her dad today.

Kerri Rawson will never forget getting the knock on her door on Feb. 25, 2005, that changed her life forever.

"It was a normal day. I had slept in," she told "20/20" her first television interview. "I was substitute teaching and I took the day off. I'm already ... uptight, thinking, 'Who is this person in my apartment building?' And then ... he said he was the FBI."

"He asked, 'Do you know who BTK is?' I was like, 'You mean the person that's wanted for murders back in Kansas?'" Rawson continued. "And then he says, 'Your dad has been arrested as BTK.'"

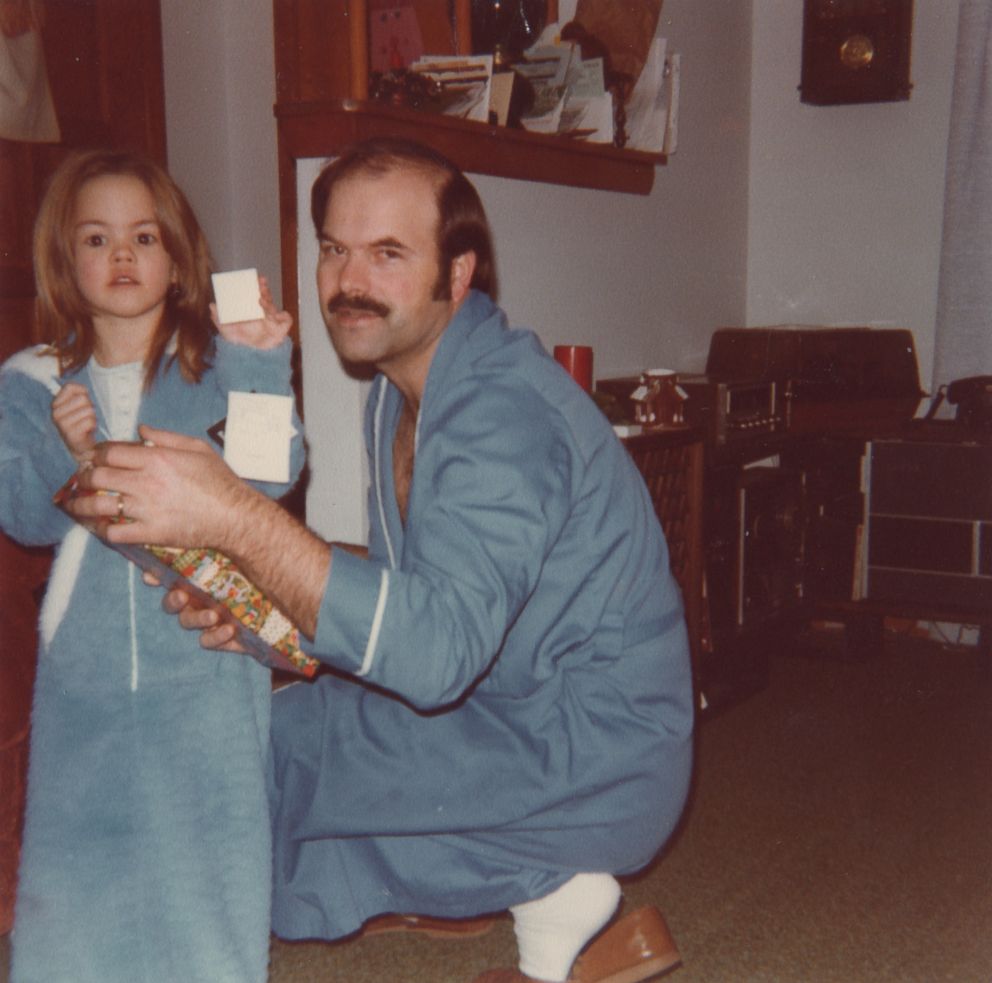

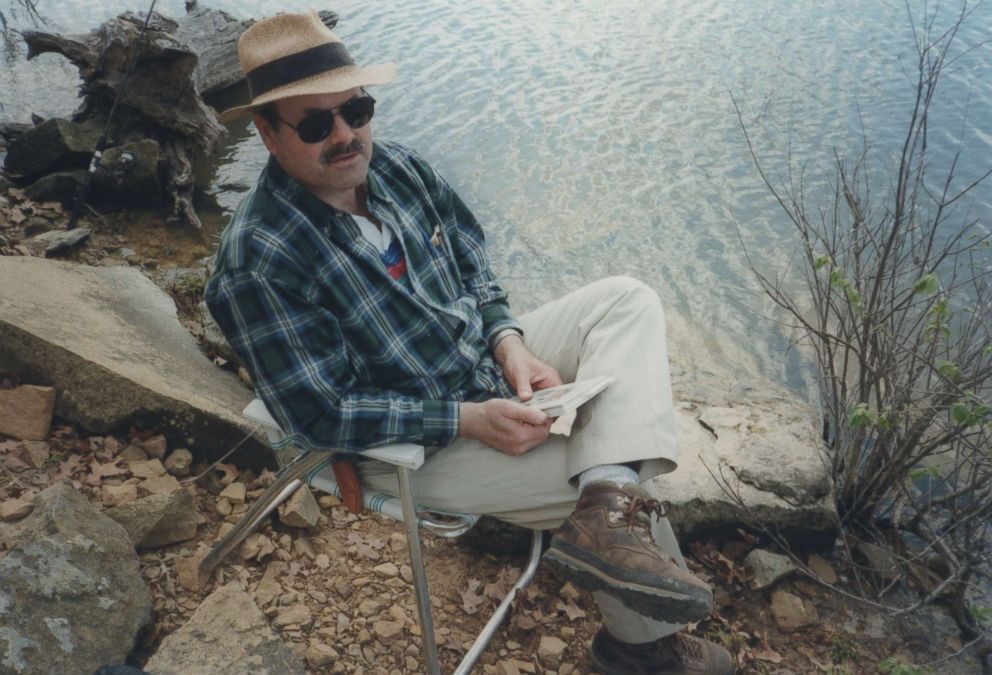

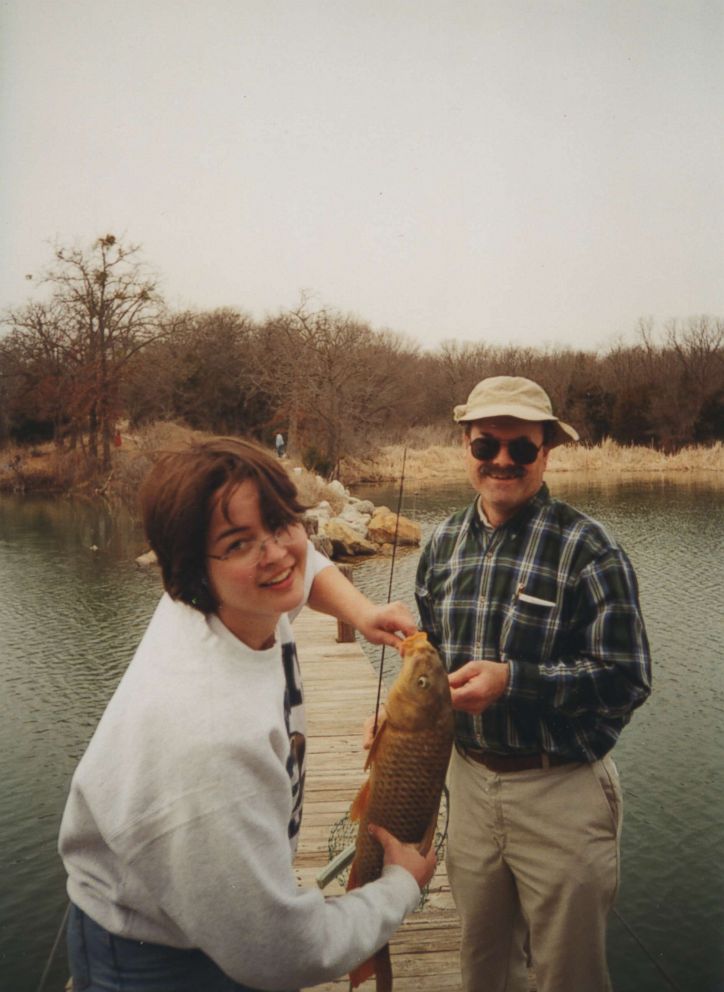

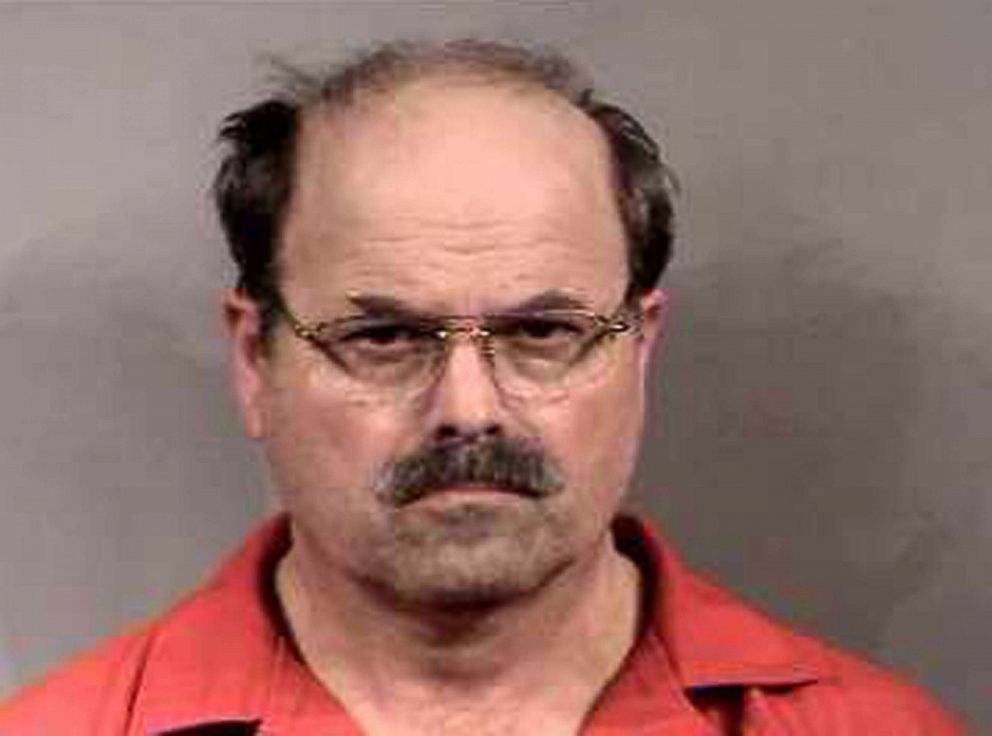

For the first 26 years of her life, Rawson knew her father, Dennis Rader, as a family man who could be a gruff at times, but who loved her. A man who was the president of his church, a Boy Scout troop leader and an Air Force veteran. A man who was nearly 60 by that point, balding and wore glasses.

Then suddenly, in a matter of minutes, he was being named among the most notorious serial killers by the FBI agent standing in Rawson's new Michigan apartment.

"I was gripping the wall next to my stove, [the room] was spinning, [I was] saying, 'I think I'm going to pass out,'" she said. "[The agent] was asking me questions about my dad, about dates and things, and I was ... trying to almost alibi my father. I was like, 'My father is a good guy.'"

"You don't want to believe it’s true," Rawson continued. "And you know ... the father you know is not capable of any of this."

The abbreviation "BTK" stands for “Bind, Torture, Kill,” a moniker Rader had given himself years earlier indicating what he had done to his victims.

I had my family. I had my husband. I had therapy. But you're, sort of, alone. It's a very lonely -- worst club you could ever imagine belonging to, being the daughter of a serial killer.

For more than 30 years, the BTK killer haunted the community in and around Wichita, Kansas, torturing and murdering 10 people, including two children. He was known for taunting the Wichita community, local media and police with letters, sometimes phone calls, seeking recognition and detailing his horrific crimes.

From the moment the FBI agent broke the news to her, Rawson said it felt like her "whole life was a lie."

In her new book, "A Serial Killer’s Daughter: My Story of Faith, Love, and Overcoming," Rawson describes struggling to reconcile the loving father she knew with psychopathic murderer known as BTK.

"It's taken me a long time to even be able to say that out loud," she said, referring to her book title. "But it is the truth.”

Rader, now 73, pleaded guilty on June 27, 2005, to 10 counts of first-degree murder. He is currently serving 10 consecutive life sentences without the possibility of parole.

Rader's killing spree began in January 1974, when he targeted four members of the Otero family, killing Joseph and Julie Otero and two of their five children. He killed 21-year-old Kathryn Bright later that year and his next two victims, Shirley Vian and Nancy Fox, in 1977.

"I was born in '78," Rawson said. "My dad murdered a young woman when my mom was three months pregnant with me."

He asked, 'Do you know who BTK is?' I was like, 'You mean the person that's wanted for murders back in Kansas?' And then he says, 'Your dad has been arrested as BTK.

To Rawson, her childhood seemed normal. She said the family lived in a three-bedroom ranch house with a dog, and a treehouse her father built for her and her older brother in the backyard.

“Most of the time, [my father] was even-keeled and kind and warm,” Rawson continued. “At times, he could be very firm or have flashes of anger or outbursts that you weren't expecting.”

“He has said himself that he just got busy raising kids and having a family,” Rawson said.

It was in April 1985 that Rader murdered his eighth victim and neighbor, Marine Hedge, who lived just six doors down.

Looking back, Rawson said she was 6 years old at the time of Hedge’s death. She believed her father was away on a Cub Scout camping trip with her older brother. Rader later told authorities he snuck away from the event that night to commit the murder and returned to the campsite in the morning.

“Somehow I knew -- at 6 -- that her body had been found and that she had been murdered and she had been strangled,” Rawson said of her neighbor. “It scared me. I started having night terrors around that time."

“I would wake up screaming, sitting up in bed, and my mom was always the one that would come comfort [me],” she continued. “She would sit there and I would say, ‘There's a bad man in my house,’ and she's like, ‘No, there's no bad man in your house.’”

Less than two years later, in September 1986, Vicki Wegerle became Rader’s ninth victim. Five years passed, and in January 1991, Rader murdered his 10th victim, Dolores Davis.

But after that, Rader, the BTK killer, went silent. For years, there were no killings, no phone calls to police, no letters left around town or sent to journalists. Most in Wichita believed he just disappeared.

If we had had an inkling that my father had harmed anyone, let anyone murdered anyone, let alone 10, we would've gone screaming out that door to the police station.

By 1991, when Rawson was 12 years old, her father got a job as a compliance officer in the Wichita suburb of Park City, Kansas. His office was down the hall from the Park City Police Department.

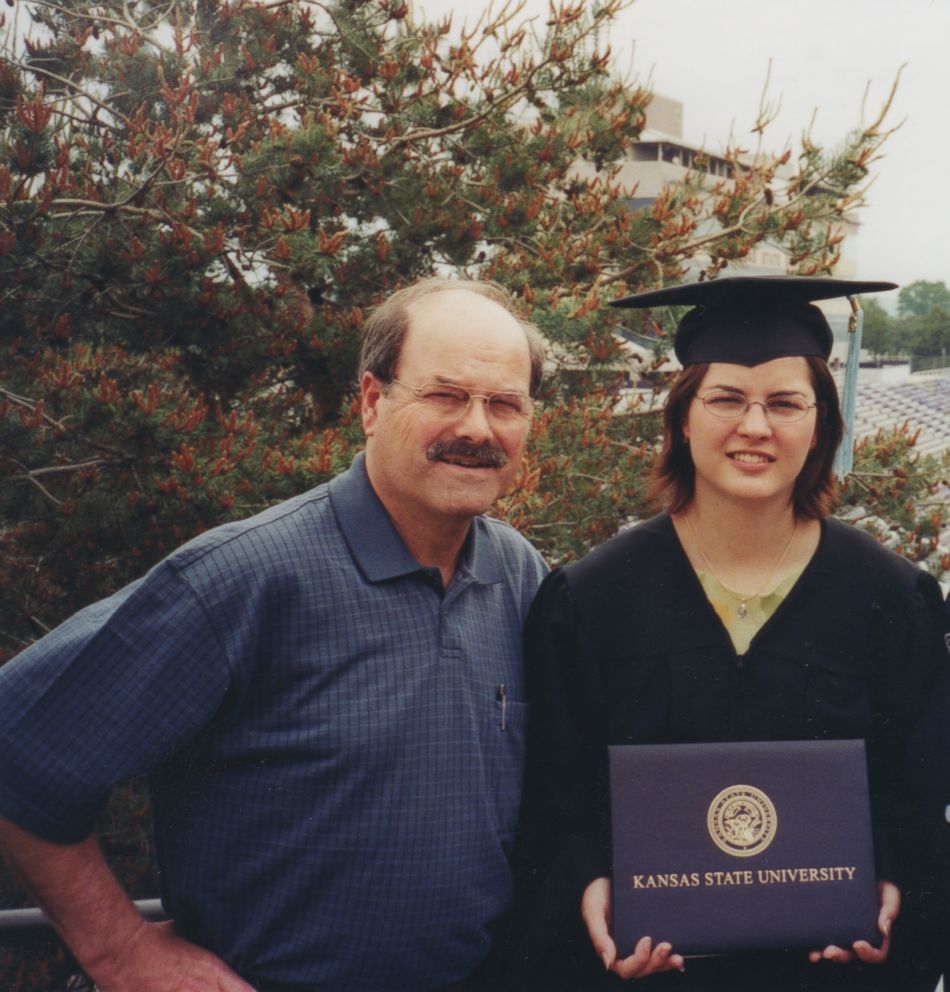

In the years after his last killing, the Rader family continued to live their everyday lives.Rawson went to Kansas State University, where she met her husband, Darian. In 2003, Rader walked his daughter down the aisle at her wedding.

Then, the Wichita Eagle newspaper ran a story in 2004 about the 30th anniversary of the unsolved Otero family murders.

“And we included in [the piece] that nobody remembered him, which invoked his ire,” said Michael Roehrman, executive editor of the Wichita Eagle.

So Rader decided to send a letter to the Wichita Eagle under the name “Bill Thomas Killman,” or “BTK” as the return address.

“I'll never forget that day,” said former Wichita Police Det. Kelly Otis. “We opened it up and it was pictures of Vicki Wegerle, who was killed in 1986 in her home.”

The reports of BTK’s return were explosive.

Rawson said she first read about the serial killer in Wichita in an article on ABCNews.com. As she started to learn more, Rawson said she assumed the killer “was a loner,” some guy who had been in trouble with the law in the past.

She never suspected the man she was reading about online would turn out to be her father.

Between 2004 and 2005, Rader sent a series of various communications to the Wichita Eagle and to ABC’s Wichita affiliate KAKE-TV -- a postcard, a letter -- and in one instance, describing the location of a cereal box left on a county road.

“Cereal boxes because serial killer,” said Dr. Katherine Ramsland, a forensic psychologist and author of "Confession of a Serial Killer, the Untold Story of Dennis Rader, the BTK Killer."

Ramsland corresponded and met with Rader over the course of five years after he was incarcerated.

“He thought this is a great joke. ... He got these dolls dressed them to look like his victims, put them into the boxes with ... some of the victims' items,” she added.

In a separate instance, Rader went to a Home Depot and dropped another cereal box containing a communication in the bed of an employee’s pickup truck, asking authorities if he could send them a floppy disk without its being traced, telling law enforcement to “be honest.”

“He says, ‘Let me know ... in the classified ads of the Wichita Eagle, that it's OK. I'll look for that ad and if I see it, give me a couple weeks to send you something,’” Otis said.

“So law enforcement put an ad in the paper that said ‘Rex, it’ll be OK,’” said Tim Relph, a Wichita Police detective. “Eventually the disk arrives, and it is taken directly to a forensics software detective.”

When investigators got into the disk’s metadata, Relph said it showed that the disk had been in a computer registered to Christ Lutheran Church and a user named Dennis.

Investigators started Googling the church and found the website for Christ Lutheran Church in Park City, whose president was named Dennis Rader.

Then began the task of linking Rader to the BTK crime spree. When the murders began in the 1970s, DNA technology had yet to be developed. But biological specimens left behind at his crime scenes had been carefully preserved, allowing authorities by 2005 to confirm the killer’s identity through DNA analysis.

In an effort to avoid tipping Rader off, authorities obtained a search warrant to access Rawson’s medical records from her college’s health center. They took her annual pap smears to get samples of her DNA for testing.

“I had no idea,” Rawson said. “It would've been nice if someone had asked me for my DNA. I would've willingly given it. I understand why nobody approached me. They needed to catch my dad. They needed to be safe about it. They needed to do it quick. ...… At the time, it felt like an invasion of my privacy.”

When law enforcement matched Rawson’s DNA to the DNA found at the crime scenes, “we knew we had our guy,” Otis said.

“Overnight we called 200 policemen,” Relph said. “We had helicopters. We had a tank. ... And we knew he was leaving work. And we were going to catch him right before he got to his house.”

On Feb. 25, 2005, police arrested Rader, who had been on his way home to have lunch with his wife. When Rawson reached her mother on the phone the day she found out, "You could just hear her [my mother] break ... just utter grief and loss," she said.

Rader eventually confessed. After her father’s confession, Rawson tried to find ways to cope with what had happened. She said a pastor at their church encouraged her to write to him as he was in jail, which she did.

“I had to learn how to grieve a man that was not dead, somebody I loved very much that no one else loved anymore,” she said.

“I wasn't corresponding with BTK. I'm never corresponding with BTK," Rawson contined. "I'm talking to my father. I'm talking to the man that I lived with and loved for 26 years. ... I still love my dad today. I love the man that I knew. I don't know a psychopath. ... That's not the man I knew and loved.”

Rawson couldn’t bring herself to attend her father’s court appearances, where he recounted how he tried to make one of his victims comfortable offering him a pillow as he was killing him.

“After my father's plea and sentencing in August of 2005, I shut down,” Rawson said. “I was mad. I was done. I wiped my hands of him for two years.”

Rawson said her mother was granted an emergency divorce in July 2005. Rawson is emphatic that neither she, nor her mother or her brother knew anything about their father’s killings prior to his arrest.

“If we had had an inkling that my father had harmed anyone, let anyone murdered anyone, let alone 10, we would've gone screaming out that door to the police station,” she said. “We were living our normal life. We looked like a normal American family because we were a normal family. And then everything upended on us.”

As time has passed, Rawson said she tried for nearly 10 years to avoid telling people she was Rader’s daughter.

“I live with depression and anxiety. I'm suffering from PTSD,” she said. “I had my family. I had my husband. I had therapy. But you're, sort of, alone. It's a very lonely -- worst club you could ever imagine belonging to, being the daughter of a serial killer.”

“The problem is if you live such a quiet, private life, it sits inside you and eats at you because it's like something you have to hide or something you have to be ashamed of,” Rawson added.

She said she wrote her dad in 2007 to let him know she was pregnant with her first child -- a daughter -- but then said she cut off communication with him again for five years afterward. She now also has a son in addition to her daughter.

“When my daughter was around 5, she started noticing, she only had one grandfather. And, you know, she was, kind of, like, "Well, where's the other grandfather?” Rawson said. “So I said, ‘You know, I have a father, but he's in jail.’ And she's just this little thing. So she's like, ‘Well, what is jail?’ And I was like, ‘Well, it's like a really long timeout.’”

Rawson said she began writing her father again in 2012, and still does to this day, because she has forgiven him.

“It was a very long journey,” Rawson said. “There was a lot of hard work in me, with faith. I had gone back to church. I was working on my relationship with God, working on my own heart.”

Rawson decided to come forward to talk about her story now, after all this time, she said, because she wants to start taking control of her story.

“[I’m] trying to say, ‘I've gone through hell. I'm still here. You, too, can overcome things. Don't ever give up. No matter what you're going through, you can get through it,'” she said.