Coal lobby fights black lung tax as disease rates surge

The Black Lung Disability Trust Fund risks insolvency due to soaring debt.

As a young man, Barry Shrewsbury dug coal in the West Virginia mines and spent his time off hunting and fishing in the rolling hills.

Now, at 62, he struggles to breathe and accomplish basic tasks such as shopping and showering, and relies on a federal fund for ex-miners with black lung disease to pay for an oxygen tank and hospital visits.

"The benefits are a lifeline," Shrewsbury said between labored breaths after a treatment at the Bluestone Health Center in Princeton, West Virginia, an industrial-style building set against the leafy landscape.

That lifeline is threatened. The Black Lung Disability Trust Fund risks insolvency due to soaring debt and a slashing of coal company contributions through a tax cut scheduled for the end of the year, according to a report the U.S. Government Accountability Office plans to publish soon, two sources briefed on it told Reuters.

That shortfall -- which comes as black lung rates hit highs not seen in decades -- could force the fund to restrict benefits or shift some of the financial burden to taxpayers, the sources said on condition of anonymity. The fund currently provides medical coverage and monthly payments for living expenses to more than 15,000 people, according to a Congressional report published this year.

The coal industry, meanwhile, is lobbying Congress to ensure the scheduled tax reduction goes forward, arguing the payments have already been too high at a difficult time for mining companies and that the fund has been abused by undeserving applicants.

“More often than not, we are being called upon to provide compensation for previous or current smokers,” said Bruce Watzman, head of regulatory affairs for the National Mining Association.

He said this position was based on "discussions with those administering this program for companies" but conceded he had no research on black lung benefits paying for smoking-related diseases.

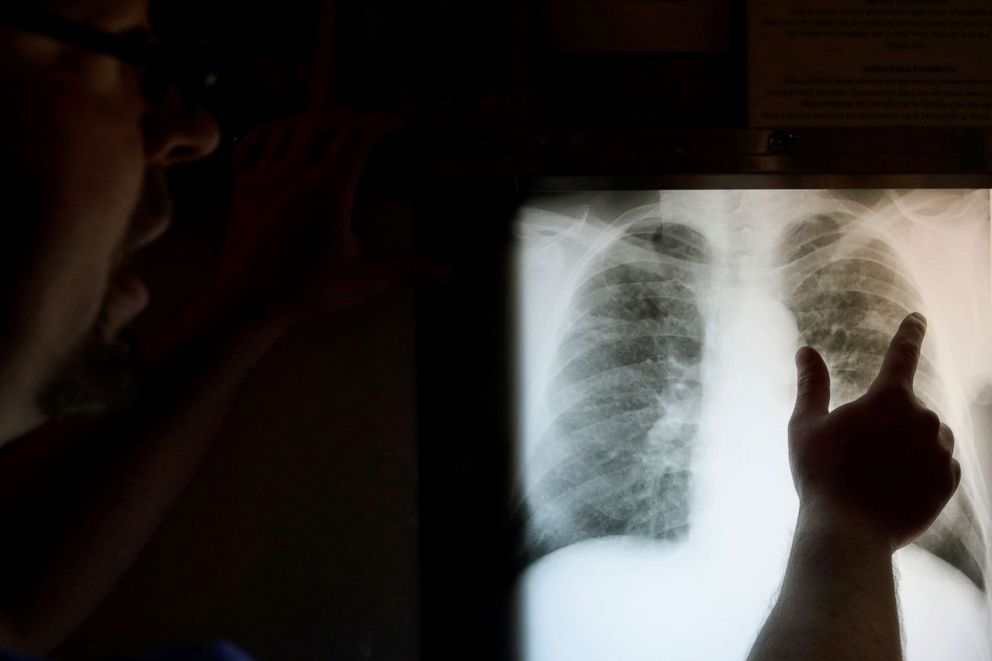

Medical experts dispute that argument, saying the disease -- an incurable illness caused by inhaling coal dust -- is easy to distinguish with x-rays.

"It is not caused by smoking,” said Dr. David Blackley, head of Respiratory Disease Studies at the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

The Labor Department, which manages the fund, considers all potential causes of an applicant’s lung problems before awarding benefits, said Amy Louviere, a spokeswoman for the department's Mine Safety and Health Administration. The approval rate for applications was about 20 percent last year, according to department data.

Coal companies are currently required to pay a $1.10 per ton excise tax on underground coal production to finance the fund. That amount will revert to the 1977 level of 50 cents at the end of the year if Congress does not extend the current rate.

The fund has already been forced to borrow more than $6 billion from the U.S. Treasury to finance benefits during the life of the program, according to the Treasury Department. About half of the fund's revenue now goes to servicing that debt.

A bipartisan effort by lawmakers to extend the current coal tax failed this year after the mining association lobbied Republican House leadership not to take it up. Watzman said he was "not at liberty" to identify members of Congress who oppose extending the tax.

Matt Sparks, a spokesman for House Majority Leader Kevin McCarthy’s office, did not respond to requests for comment.

Lawmakers expect discussion of the tax to resume after the GAO report is released.

“We need to take care of the miners,” said Virginia Republican Congressman Morgan Griffith, who represents a district that has seen one of the biggest surges in the disease. “We first need to have all facts on the table.”

The mining association and large miners such as Peabody Energy, Arch Coal and Consol Energy are already pressing their case, according to Congressional lobbying records that show the black lung fund among the subjects discussed in their recent meetings with lawmakers.

Peabody CEO Michelle Constantine declined to comment. Arch spokesman Logan Bonacorsi and Consol spokesman Zachary Smith did not respond to requests for comment.

The upcoming GAO report was requested in 2016 by Democratic Congressmen Bobby Scott of Virginia and Sander Levin of Michigan and has undergone review by the administration of President Donald Trump, who has focused on slashing regulation to help the coal industry.

White House spokeswoman Kelly Love did not respond to a request for comment on the administration’s position on the excise tax.

The fund pays benefits to miners severely disabled by black lung in cases where no coal company can be found to directly provide support. That typically occurs when a company has gone belly-up -- an increasingly common scenario as the nation's utilities shift to cheaper natural gas and cleaner solar and wind power.

Some 2,600 medical claims were transferred from companies to the fund in 2017 due to bankruptcies, according to a Congressional report this year.

Government research shows the incidence of black lung rebounding, despite improved safety measures adopted decades ago -- such as dust screens and ventilation -- which had nearly eradicated the disease in the 1990s.

In February, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health confirmed 416 cases of advanced black lung disease in three medical clinics in rural Virginia from 2013 to 2017 -- the highest concentration of cases ever seen. It also confirmed a 2016-2017 investigation by National Public Radio that found many hundreds more cases in southwestern Virginia, southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky.

“This is history moving in the wrong direction,” said Kirsten Almberg, an assistant professor of environmental and occupational health at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

Almberg authored an analysis of Labor Department data showing that nearly half the 4,679 benefits claims from miners with the worst form of black lung disease were made since 2000.

Ex-miners and regional health experts blame the resurgence on longer hours spent in deeper parts of old, played-out mines, along with lax safety measures and the use of heavy machines to blast through layers of rock.

“We didn’t use curtains. We rarely used ventilators. We thought we were invincible,” said Greg Jones, who left mining in March and now coordinates benefits applications at the Tug River Black Lung Clinic in Gary, West Virginia.

Brandon Crum, a radiologist at the United Medical Group in Pikeville, Kentucky, said he has personally diagnosed more than 150 cases of advanced black lung disease since 2016, many in younger miners.

Crum, whose own family worked the mines for a century, said many of these people face a lifetime unable to work, inundated with medical bills.

“Any kind of asset or financial stability you would take away from these miners and their families would be devastating,” he said.

To qualify for benefits, a miner must apply to the Department of Labor, which screens the applications based on medical and employment documentation and then tries to find a responsible coal company to pay the costs.

Jim Werth, the black lung clinic director at Stone Mountain Health Services in St. Charles, Virginia, said his clinic has three people on staff helping patients file for benefits. He rejected the idea that the fund was covering undeserving applicants, saying the process already makes it hard to qualify, with coal companies often hiring doctors to dispute medical test results.

William McCool, 64, said it took him years to win benefits.

"I worked 40 years in the mines, and the benefits don't come automatic," said McCool, who wore a grey baseball cap emblazoned with a crossing pickaxe and shovel during an interview at the Mountain Health Center in Whitesburg, Kentucky, where he receives oxygen and physical therapy.

Kennith Adams -- a 62-year old former miner who survived stage-four colon cancer and is now suffering advanced black lung -- had his first application rejected two years ago, he said.

Consol argued he did not work for the firm when he became ill; Adams had worked at the Bishop Coal Company, which later got taken over by Consol.

Consol did not respond to a request for comment.

Adams and his wife Tammie are now hoping his latest application -- sent last month -- will be approved to help them pay medical bills of more than $12,000 a month.

"If he doesn’t get his medicine," his wife said, "he doesn’t stand a chance."

Reporting by Valerie Volcovici