After George Floyd's death, police confront lack of diversity in leadership

Nearly 1 in 3 U.S. officers are non-white, but fewer are department leaders.

Many minority police officers have found themselves in a unique position during the current debate over police reform.

Members of black and Latino police associations say their members have experienced both what it feels like to be targeted by prejudice because of the color of their skin and because of the color of their uniforms.

RaShall Brackney, chief of police in Charlottesville, Virginia, and a member of the National Organization of Black Law Enforcement Executives, told ABC News it's been tough for many black officers to patrol the streets.

At the same time, Brackney said, minority officers may now have a better environment in which to express their concerns and potentially improve policing for everyone.

"If you don't have those black leaders at the table ... the ability for genuine reform is going fail," she told ABC News.

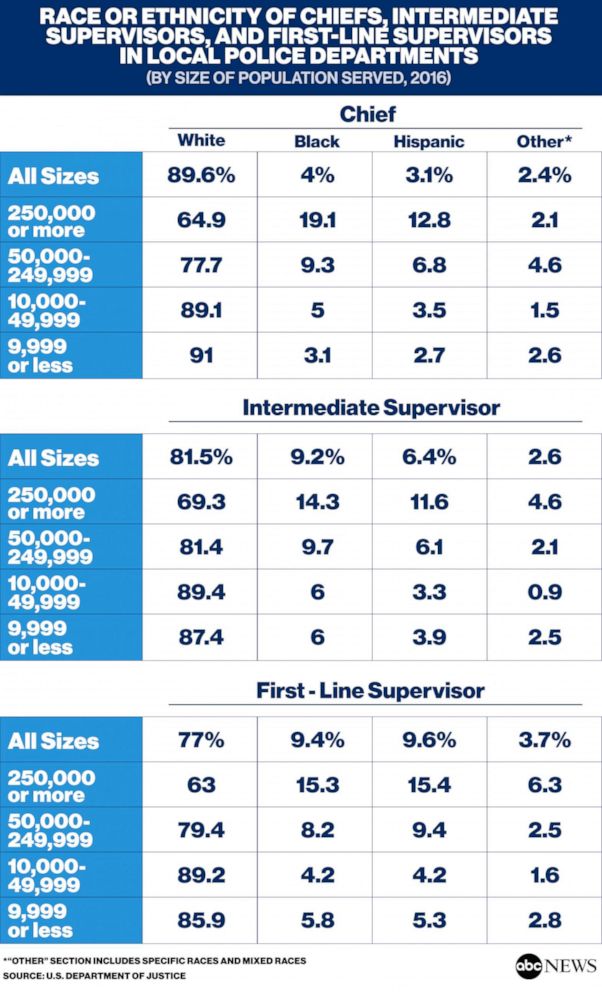

The key roadblock for many of these officers has been ascending to leadership roles. Although police departments nationwide are increasingly diverse, very nearly mirroring racial breakdowns throughout the U.S., too few non-white officers find themselves in top positions.

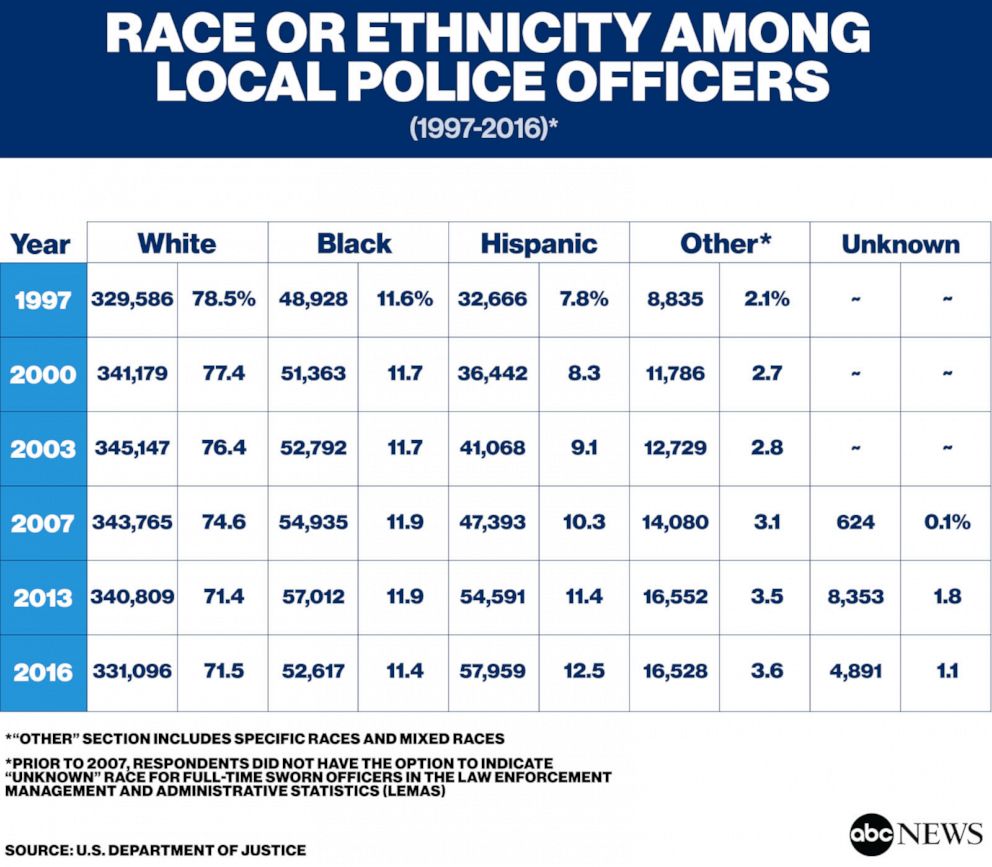

A report released last year by U.S. Department of Justice's Office of Justice Programs said that between 1997 and 2016 the number of black officers increased by 3,689, the number of Latino officers jumped by 25,293 and the number of those belonging to another minority group grew by 7,693 nationally. During the same period, the number of white officers increased by just 1,528.

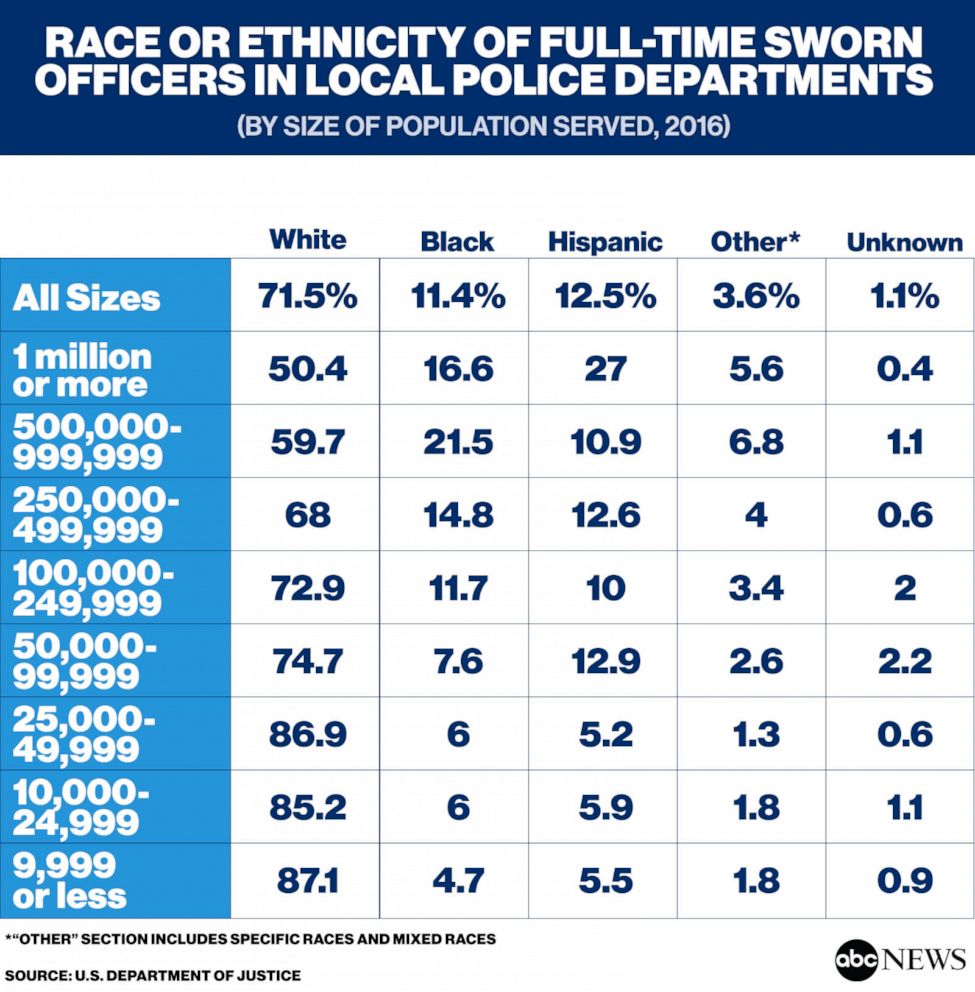

White cops make up 71.5% of police, while black officers represent 11.4%, Latinos 12.5% and other minority groups 3.6%, the report said. By comparison, the latest U.S. Census data shows whites are 72.3% of the population, blacks are 12.7%, Latinos are 18.1% and Asians make up 5.6%.

But the Department of Justice report found that nearly 90% of police chief roles, 81.5% of intermediate supervisor roles and 77% of first-line supervisor roles had been assigned to white officers. And in police forces that serve populations under 50,000, the percentage of white officers on the force is no lower than 85%.

Anthony Chapa, the executive director of the Hispanic American Police Command Officers Association, said the best way for the public to regain trust with law enforcement is to have more minority officers in departments, especially in high-ranking positions.

"The future of law enforcement needs to change and have more diversity," Chapa told ABC News.

The Hispanic American Police Command Officers Association said George Floyd's death damaged years of progress his officers had made building up trust in minority communities.

"We are ACCOUNTABLE to self, our agencies, and the local community at large," HPCOA said in a statement.

Jack McDevitt, director of the Institute on Race and Justice at Northeastern University's School of Criminology and Criminal Justice, said recruiting minorities to law enforcement has always been tricky because of bad relations between police and their communities. On top of that, minority cops who are looking for promotions are sometimes hit with more burdens related to their tougher financial situations, according to McDevitt.

"One of the things that happens, sometimes, is white officers will have more ability to study for promotion and get promoted," he explained. "They usually won't take an overtime shift to help pay for their family and have more leisure time to study for those tests."

Scott Wolfe, an associate professor in the School of Criminal Justice at Michigan State University, said city and police leaders have to go beyond recruiting minorities. While the minority cops increase their visible presence through associations, there is still peer pressure from the more experienced officers to conform to a traditional view on policing that doesn't take into account concerns from communities of color.

"Even if you have more minorities in police departments, policing is a close-knit of individuals," Wolfe told ABC News. "They will be hesitant to call out their own, even if they don't agree with them."

Brackney, a 36-year veteran of the force, acknowledged this struggle. For years, she said her peers deemed her the "affirmative action officer" or "token cop.”

"You name any type of slander, it's been thrown at me," she said.

However, over the last few years as she and other officers have been promoted to top positions and as residents have called for change, Brackney said more officers are beginning to speak up.

"The ability to trust genuine reform is difficult and challenging. You need those leaders like NOBLE to come forth to say we're willing to help, but we won't unless we have the ability to influence that our counterparts have," she said.

During the last few weeks, the chief said the public, elected officials and police brass have been more receptive to hearing what NOBLE and other groups have to say on police matters since they have had their ear to the community for a long time.

In some cases, she said, departments should scale back their presence and that she supports "re-funding" police, spending more to deal directly with mental health emergencies or school truancies in nonviolent ways.

"I'm sure most police professionals would not want to be to be the ones operating in those incidents," Brackney said. "If you dial 911 and you are in a mental health crisis, there should be a mobile mental health team sent to you."

The chief said she was confident departments throughout the country will take the input from their black members very seriously and work to ensure civilians and officers can move forward.

"There is now a need to rely on our experiences and expertise to negotiate how policing in the communities will look like," she said.