'Godsend': The vets and volunteers who cared for 9/11 rescue dogs

Veterinarians and volunteers sprung into action to care for the rescue dogs.

They suffered burns, cuts and dehydration as they sorted through rubble of the World Trade Center for hours on 9/11, looking for survivors and human remains. They were the search and rescue dogs at ground zero.

One dog, Apollo, survived after being engulfed in flames. Another dog was saved after falling almost 50 feet.

About 350 dogs relentlessly searched "the pile" for months, often becoming depressed when their search yielded no results, according to veterinarians, humane society members, and others who were at the scene who spoke with ABC News.

Keeping the dogs healthy enough to continue their dangerous work was a major challenge and veterinarians, many of whom voluntarily pulled themselves away from their practices; members of the New York Police Department's Emergency Services Unit, canine division; and volunteers and officials from the Suffolk County, New York, Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, all helped care for them.

With caregivers’ help, search and rescue dogs worked around-the-clock in shifts. The dogs' ability to detect even the most miniscule fragments of human DNA among the rubble, allowed forensic investigators to identify many of the 2,977 people killed at the site.

In addition to caring for search dogs, vets and volunteers also aided in rescuing pets who had been left stranded in apartments all around ground zero after authorities locked the area down. They provided first aid to human first responders caring for eyes encased in ash and providing pain medication.

The animal caregivers at ground zero worked 24/7 for months at the site. Prior to 9/11, there were no official standards in place for dealing with animals at disaster scenes, veterinarians and officials who spoke with ABC News said.

Below are personal accounts from several animal caregivers who spent weeks, sometimes months, at ground zero. The transcripts have been edited for clarity and length.

Roy Gross, Suffolk County SPCA Chief

Gross helped lead the effort to create a mobile animal spay clinic, the first of its kind in New York state, and one of only three such units in the country at the time of 9/11. That mobile clinic became an emergency mobile animal hospital at ground zero.

Dehydration was the biggest issue that we had. These dogs had to be washed, obviously, because they were covered in contaminants. They couldn't smell anything, they were so covered. While they were washing them they actually had them plugged in with IVs to rehydrate. Their eyes had to be irrigated with saline solution.

There was another dog that I remember. And he was coming in towards the mobile hospital. I can see the dog is collapsing. And [his handler] gets the dog over. [We gave the dog] food, water, whatever he needed. And then the dog starts pulling his handler back to the pile like he knew he had a job to finish. I don't remember which dog that was. I just remember witnessing that.

There was probably 350 dogs in total, from all over the country as well as other countries. And we provided somewhere between 700 and 1,000 treatments during that period of time that we were there. There were probably about 200 veterinarians that were down there for almost two months. This was 24/7, constantly treating these dogs. I mean, they couldn't do this, without that help.

People needed to get to their apartments to get their pets. Our peace officers escorted these people to their apartments to retrieve their pets and get whatever personal belongings. One of our officers … he was going up and down the stairs rescuing these animals from their apartments and he collapsed.

We also had therapy dogs. My dog was not trained for search and rescue. But I brought him. I was just standing there one time with the dog. A fireman comes down. He's walking towards me. And he gets down on his knees and he starts petting my dog. And then he starts to cry. There he is petting the dog and he opens up and he starts talking and he opens up -- what a difference it made.

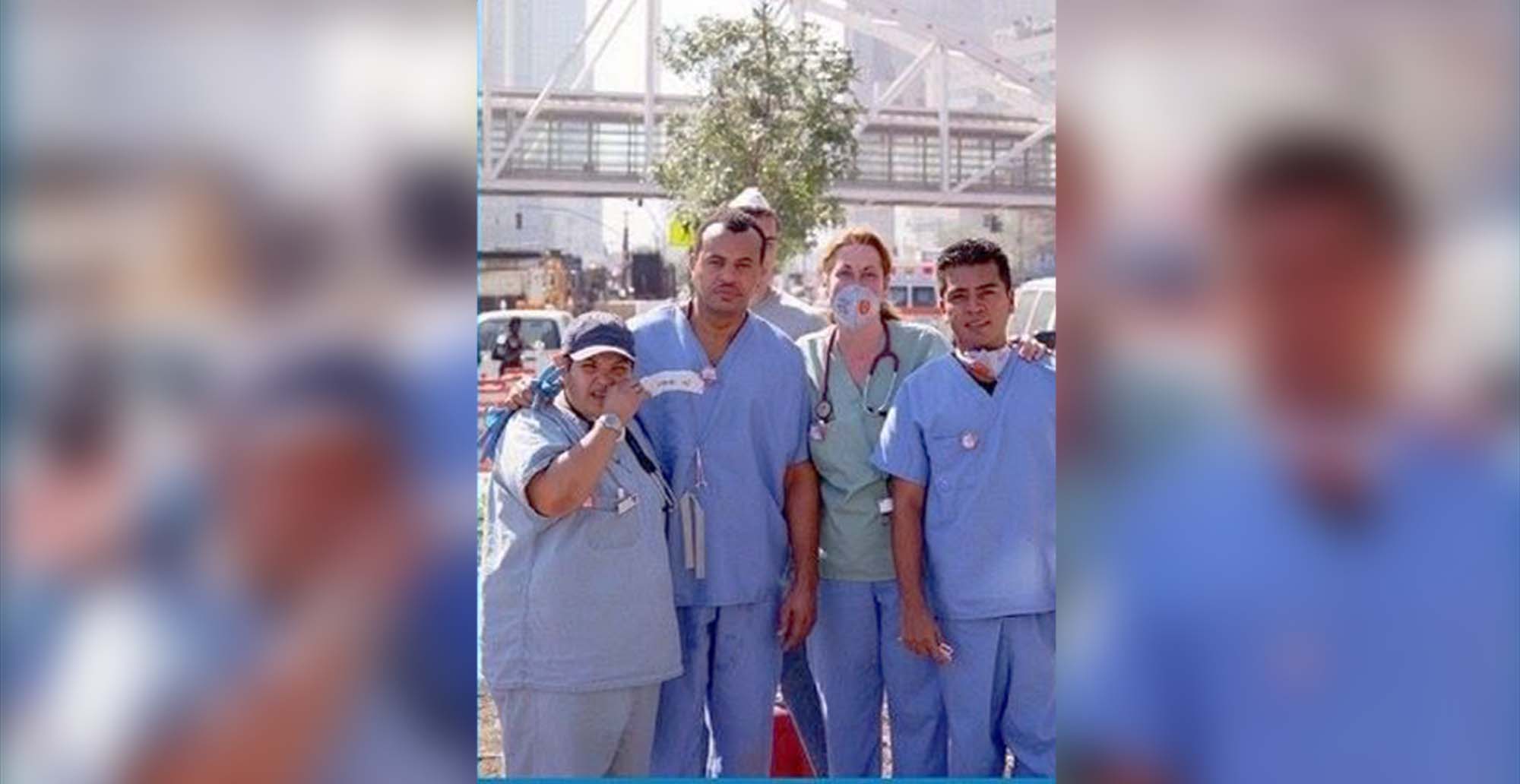

Dr. Michael Shorter, veterinarian:

Shorter, along with his partner, Dr. Barbara Kalvig, were among the first vets to arrive at ground zero after seeing the South Tower fall. They headed downtown from their veterinarian practice on the morning of 9/11, thinking they would offer their expertise as medics for human victims. Instead, they ended up caring for the search and rescue canines. Their work helped set protocols for attending to the needs of search and rescue dogs -- still in use to this day by the Office of Emergency Management of New York City for animal disaster response.

We started realizing that our role would be more or less treating the search and rescue dogs … all these handlers and dogs began to mill around covered with dirt and dust. One individual had a dog, an older dog named Bear that was totally covered in debris and dust. He told us: "we need supplies down here we need some help."

These dogs were just frantic. Cadaver dogs and these recovery dogs are trained to find a body. You're talking this pulverized organic matter; scent is everywhere -- they don't know where to focus.

This grassroots effort of veterinarians … got the attention of Office of Emergency Management … nothing had been in place prior to this. There had been no protocols or anything for addressing a disaster situation where you had animals or pets.

From that, we formed this group called NYC VERT, which is the New York City Veterinary Emergency Response Team.

Lt. Daniel Donadio, NYPD ESU Canine:

Donadio was the NYPD's ESU canine division's first responder in charge of 9/11. He was a liaison between the NYPD and the caregivers.

A FEMA search and rescue team, they come in for a week, and they rotated out. And after about three weeks … rescue recovery was left to one unit. And that was the NYPD canine unit.

The dog part of the recovery unit was my dogs; only the NYPD dogs. And they [were] on a rotation basis for a full nine months until the last day of May 30.

[The veterinarians] were a godsend. The dogs would work for a while, the team would go off to the mobile vet, first get the dog washed down, and then maybe go someplace and get something to eat.

Officer Joseph Caputo [a member of the New York City Police Department Emergency Service Unit’s canine team], let him rest in peace [Officer Caputo died in 2014]. I sent him to represent us at a function so we're in uptown Manhattan and I don't remember where it was Kennel Club or whatever. But he was approached by a woman who said, I just want to thank you and your unit ... your dogs found my son.

Dr. John Charos, veterinarian:

Charos, after hearing the towers were under attack on the radio, loaded up his car with medical supplies and headed to ground zero from his practice in Long Island, New York.

We did 12-hour shifts for continuity with the handlers because … they don't want to come in with their [dog] partner and see a different vet every time.

We used combinations of a little bit of peroxide with a surgical scrub called chlorhexidine [to clean the dogs]. Some of the [handlers had been using] Tide detergent and the dogs were getting skin issues.

People started bringing their own tents. We needed water obviously … the fire department isolated a hose [for us]. Another doctor came down with camping equipment, a turkey fryer and a Coleman outdoor shower. We used the turkey fryer to heat the water to mix with ice cold water so we could shower the dogs down.

The FEMA team came in after the first week. Prior to that, it was really just the grassroots of local veterinarians, primarily from Long Island, New Jersey and some from [New York City]. Dr. Michael Garvey was a godsend down there, representing the Animal Medical Center. He was triple-board certified. He was a valuable resource already for infectious disease and anti-terrorism prior to 9/11.

[Garvey, a veterinarian who Dr. Charos credits with helping set up the animal first aid at 9/11, died in January 2020, according to the Animal Medical Center's website].

In the beginning, we were treating humans: aching heads; smoke in their eyes.

Someone from the fire department came in with a box and said, "Save him, save him." When we looked in the box, there was a pigeon that they uncovered that was buried in the rubble. It was the only live thing I saw from that pile. [They] treated the pigeon.

There was another fellow that came in with a Dalmatian; was an older gentleman. And we got to talking. I think he was fearful that he didn't belong down there. But his son was in the fire department; he was trying to find his son out there.

Gerry Lauber, chief of detectives, SCSPCA:

Lauber received a call from someone he knew at the NYPD who asked him to bring his team down to 9/11 after the attacks.

We set up a procedure where any of the dogs that were coming to the scene would register with us. So they would know that they have service available to provide support. We were the only humane society at ground zero to provide services because at the time many of our members were also special deputy U.S. Marshals and since it was a federal crime scene it gave us additional authorization to work.

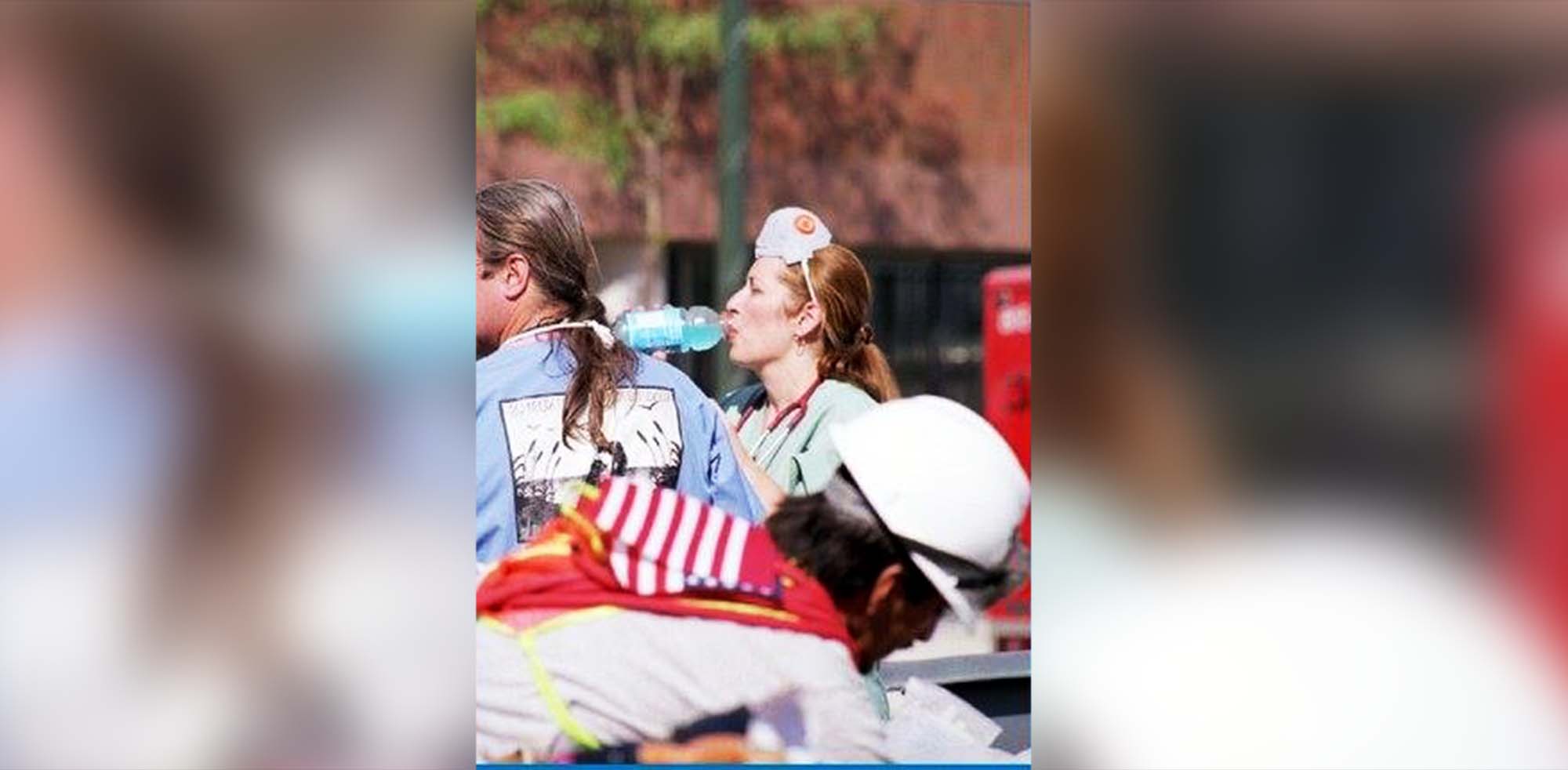

Dr. Barbara Kalvig, veterinarian:

Dr. Kalvig was instrumental in mobilizing 197 veterinarians and about 100 veterinarian technicians in the effort at ground zero. She and her team supported 24-hour veterinary operations at the site. She helped establish protocols for the veterinarian response that could be used in future disaster scenarios.

When we arrived at the first area of triage --- we were filled with adrenaline and anticipation-- we were filled with fear of what we would see and determination to stay strong to help however was required.

After the veterinarian work at ground zero was finished, a request for help from OEM came to us for animal-related disaster response in New York City. The NYC Veterinarian Emergency Response Team was formed and was stationed at events with working dogs such as at the U.S. Open and the Republican National Convention-- regular meetings with the city were held-- [Hurricane] Katrina happened -- suddenly [there was] a different disaster. Forty percent of people won’t leave pets behind in disasters, [studies show]. Many things evolved in New York City just in time for the response to [Hurricanes] Irene and Sandy.

[9/11] was the first event like this -- it was an overwhelming disaster event. Everyone was fighting against time to work as fast as possible for rescue and recovery --- everyone purely did what needed to be done -- no smartphones -- record keeping would be much different today.

Twenty years later we still find ourselves with grave need for national coordination (think COVID) and individuals who are working on that, this includes animal disaster response.