Judge, DA apologize to man who was exonerated after 28 years in prison: 'We failed'

Witnesses recanted testimony and police withheld evidence, investigators found.

Chester Hollman spent 28 years behind bars, knowing every single day that he served that he is innocent.

Now the court knows that too. Hollman had his conviction overturned, his charges dropped and he is now fully exonerated.

Hollman's exoneration had been in the works for years, through various efforts to have him freed, but it wasn't until the case was reviewed by Philadelphia' District Arttorney's Office's Conviction Integrity Unit in January 2018 that the wheels of justice began to turn.

"He's a full spectrum of emotions," Hollman's longtime lawyer Alan Tauber told ABC News.

Two witnesses who originally testified at the 1993 trial recanted their earlier testimony, saying that they did not actually see Hollman at the scene of the murder of a college exchange student in Philadelphia in the early morning hours of Aug. 1, 1991.

The Philadelphia Inquirer reports that those witnesses have since recanted their testimony -- with one of the witnesses recanting hers in 2012 before the judge that exonerated Hollman on Tuesday.

As part of the Conviction Integrity Unit's probe, investigators determined that when that witness recanted in 2012, a detective who denied her claims had accusations of wrongdoing made against him in another case, which would have raised doubts about his integrity to the judge when presented with the witness's new testimony in 2012.

If you want to see what grace looks like, look into the face of Chester Hollman.

Tauber said that Hollman, now 49, holds no grudges against the witnesses.

Tauber told ABC News that he asked Hollman "how are you not angry at the peple who gave false testimony against you?'"

"He says 'How could I be angry at them? they're victims too,'" Hollman said, suggesting that the police pressured their testimony.

"I said to the judge, 'if you want to see what grace looks like, look into the face of Chester Hollman," Tauber said.

The Conviction Integrity Unit also discovered that police withheld information that could have led to other suspects, The Inquirer reported.

"We believe it was near-impossible Chester Hollman was the perpetrator of the crime," Assistant District Attorney Patricia Cummings, head of the Conviction Integrity Unit, said in court on Tuesday, according to the newspaper.

"I apologize to Chester Hollman," Cumming said. "I apologize because he was failed, and in failing him, we failed the victim, and we failed the community of the city of Philadelphia."

She wasn't the only one to apologize on behalf of a major institution, as the judge who oversaw Tuesday's motion hearing to dismiss the charges against Hollman also apologized on behalf of the court.

"This is one of those bittersweet moments where [there is] joy in the fact that justice has been served, but sadness in the fact that it has taken so long,” said Common Pleas Court Judge Gwendolyn N. Bright, according to The Inquirer.

Tauber said that he's "never" seen that extent of a formal apology in the two or three exoneration cases he has handled previously, and found it "very remarkable" and "extraordinarily gratifying."

"I personally was not expecting that. I believe it was the right thing to do," Tauber said of the apology.

Tauber said that Hollman "was extraordinarily moved, he was brought to tears several times throughout the proceeding."

The Inquirer reported that Hollman made a few comments in court Tuesday, saying that he grew up wanting to be a police officer and he struggled to hold on to hope as years passed, but throughout had enjoyed the continued support of his family, including his mother, who passed away while he was in prison.

Tauber told ABC News that Hollman is now staying with his father in Wilmington, Delaware, as he adjusts to his newfound freedom.

"He's been slowly but surely acclimating with the fact that he's free," Tauber said, as Hollman was released from prison two weeks ago but the hearing this week was to formally dismiss his charges with prejudice, meaning that they cannot be refiled in the future.

Tauber said that Hollman is adjusting to some of "the simple interactions of daily life" that don't exist in prison.

"He's slowly but surely get a grip on the fact that he doesn't have to get permission to go up to the second floor of his house," Tauber said.

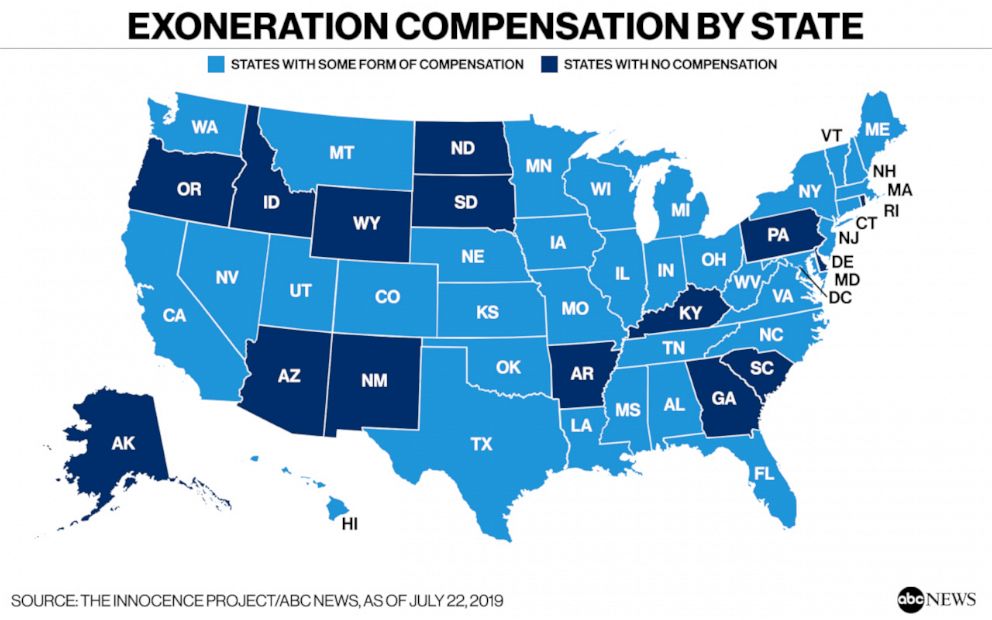

Pennsylvania is one of 15 states that have no state exoneration compensation in place, meaning that exonerated men and women, like Hollman, have no avenue to collect compensation from the state after time wrongly served.

Like every exoneree, Hollman could file a federal lawsuit if he and his lawyers feel that his federal civil rights were violated. That route is widely-viewed as having a much higher threshold than state compensation cases.

Tauber said that he would not necessarily be part of the legal team that would help Hollman make a decision about a civil suit, when and if he decides.

For now, Hollman is adjusting to life outside.

"He's going about becoming a regular citizen: getting a license, getting health insurance, starting to get some counseling and think about his future," Tauber said.