Will the state pay you for a wrongful conviction? Depends on the state.

For many, the varying exoneration compensation laws mean a second legal battle.

NEW ORLEANS -- Malcolm Alexander has a complicated relationship with time.

He always wants to be early to his new job, which comes out of a desire to make a good impression, but his wife said that she needs to convince him that he doesn't need to be 35 or 40 minutes early.

The fact that he doesn't want to waste a day makes sense, considering he spent the last 38 years in one of the country's most notorious prisons after being wrongly convicted.

Alexander, 59, now free, makes a few dollars above the state minimum wage as a semi-skilled laborer for the local government, but he stands to win more from the state.

As DNA evidence is leading to more and more exonerations of old cases, and with calls for criminal justice reforms on the state and federal level, the question of what the government owes to the people it wrongly convicts is up for debate.

Louisiana is one of a majority of states that have some form of exoneration compensation, though it's not much: the state allows for a maximum of $250,000, paid out over 10 years.

For Alexander, if he's awarded that much, that's still just $6,580 per year he was imprisoned.

After being exonerated in January 2018, he married Brenda, his middle school sweetheart and the mother of his now-grown child, also named Malcolm.

When he was 19, Alexander was wrongly accused and convicted of sexual assault. He was a high school dropout who'd planned to return to school and either become a mechanic or a long-haul trucker like his father.

"I was satisfied with that path," he said. But the life sentence that he was given, without the possibility of parole, changed everything. Now he works for Jefferson Parrish in Louisiana earning $10.47 an hour -- after a recent pay raise.

"I am, at 59 years old, more of a retirement age, and I'm doing like a 20-year-old man's job," Alexander said.

"Me actually trying to adjust mentally, it actually has been a struggle," he acknowledged. "My finances, it's just, I'm not comfortable. I am -- how you would say? -- I'm living a day-to-day life right now."

He said that while he was incarcerated at the Louisiana State Penitentiary -- more commonly called "Angola," after the plantation previously on that land -- he worked jobs that he said paid 2 or 3 cents an hour. He supplemented that by selling plasma to help buy presents for his then-young son.

Now that he's out, he wants to be able to help, but he can't afford it -- like when his son bought him and his wife lunch the day prior. It was out of kindness, but that's a kindness that Alexander doesn't want to have to accept anymore.

"It's just the thing of standing on my own is what I'm fighting to try to get to," he said. "The institution was easy because I didn't have no overheads. Here I have overheads and it piles up each day."

He's made adjustments to the way that life operates outside of prison -- like following Brenda's advice that he stay in the middle lane to avoid people he thinks are driving too quickly.

But the prospect of compensation from the state is something that he and so many exonerees – but not all – have to grapple with.

From millions to nothing, state compensation laws vary dramatically

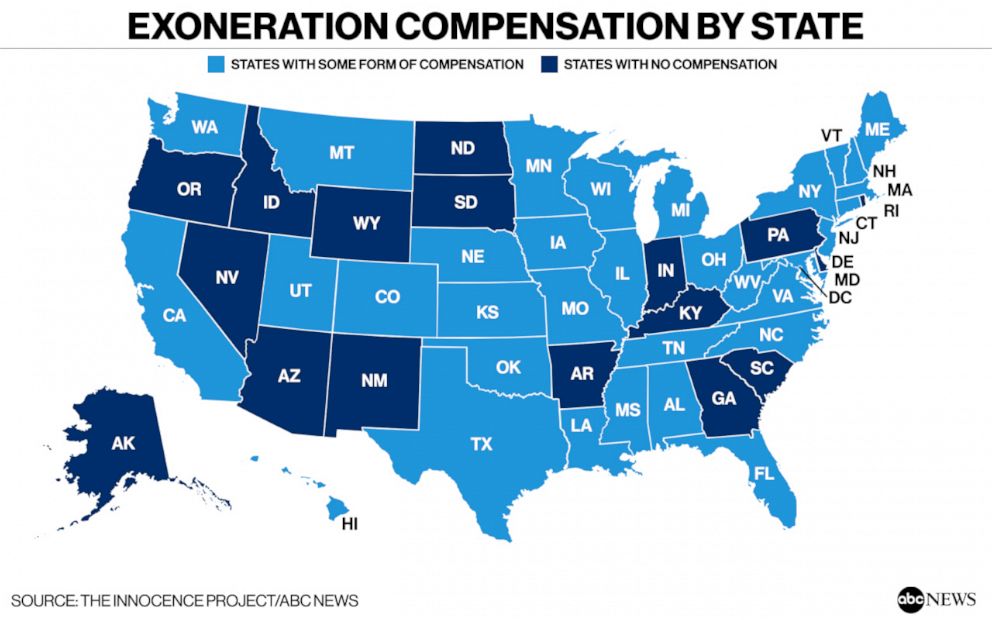

There are 17 states without exoneration laws. That means that exonerees there – like those in states with compensation laws – are left to decide if they have enough of a case to file a federal civil rights case for a wrongful conviction and imprisonment.

Jeff Gutman, a professor of clinical law at the George Washington University Law School who's studied exoneration compensation, said that typically in such cases, the individual "needs to show that some state actor engaged in constitutional misconduct," like, for example, the police failing to hand over exculpatory evidence to the prosecutor.

Essentially, all exonerees can try to go the civil rights violation lawsuit route, but not all cases meet that standard. And only those who are in the 33 states with compensation laws can get any money from the state.

In the states that do have the laws in place, most exonerees do seek to get the state funds, but not all. Gutman explained that in some of those instances, lawyers likely made a "strategic judgment" that a federal civil rights case is stronger, or, "in other cases, the state statute is profoundly ungenerous and therefore just isn't worth it."

I am, at 59 years old, more of a retirement age, and I'm doing like a 20-year-old man's job.

There is a wide range in what different states offer, according to data compiled by The Innocence Project.

New York has no limit to how much an exonerees may be awarded. California allows for a maximum award of $140 per day wrongly imprisoned, so had Alexander being wrongfully convicted and imprisoned there, he could have been owed upwards of $2 million.

Mississippi allows for $50,000 per imprisoned year with a $500,000 cap and some attorney's fees, while Nebraska also has $500,000 a cap, but no annual stipulations.

On the other end of the spectrum, New Hampshire has a $20,000 cap. Wisconsin allows for $5,000 per year wrongly imprisoned but has a cap at $25,000, but a review board can petition for extra funds.

Montana allows for tuition, room and board at a state community college, but no monetary amount.

Loopholes and logistics

Some states have stipulations that mean that even if an individual was wrongly convicted and later exonerated, the person isn't necessarily eligible for the state's compensation. In Washington D.C., and in states including Iowa and Oklahoma, the claimant must not have pleaded guilty. Or in Florida, those seeking compensation for being wrongfully convicted can't receive any compensation if their record includes prior felonies.

Robert Norris, assistant professor of criminology law and society at George Mason University and the author of "Exonerated," said there's a moral and practical struggle in determining compensation laws.

"The biggest argument I've ever heard [against compensation laws] is the financial cost, but if you have any faith in your system, then that really shouldn't be an issue," Norris said. "Ultimately we're trying to put a value on years people lost, and so there's a question of 'is any amount of money ultimately adequate or enough? And where is that line ultimately?'"

Norris said that in addition to financial assistance, there's a big benefit to states offering some kind of social services for the recently exonerated. He pointed to Texas, which offers $80,000 per wrongly imprisoned year plus an annuity and some reintegration and financial assistance as well as legal fees and missed child support payments, as an example of a state taking a more comprehensive approach.

"Exonerees are basically cut loose. It's like 'Well, you're innocent, you don't' belong here. Just go,'" Norris said.

For his part, Gutman thinks that there are going to be more and more states adopting some form of compensation.

"Indiana is close to passing one," he said. "I know Nevada and Rhode Island are considering them. I don't know that we'll get to a place where every state has one, but there's definitely been progress."

While Louisiana's cap of $250,000 isn't the lowest, Emily Maw, senior counsel at Innocence Project New Orleans, said, "It's one of the worst."

She said that, in part, that stems from the difficulty that comes with ascertaining that compensation, even after an exoneration.

"I don't believe it was intended to be as cumbersome, but the fact that it has proven to be demands that we change it," Maw said.

The long road to a payout

That's been the case for Jerome Morgan, who was exonerated after spending 20 years in Angola for a murder he didn't commit.

Morgan walked out of prison in January 2014 and was formally exonerated in May 2016. It was ruled that he would be awarded compensation in March 2017, but it wasn't until August 2018 that he received his first payment of $25,000.

Morgan, 43, told ABC News that when he got that payment -- more than 4 1/2 years after leaving prison -- it wasn't even enough to cover the debt he had accrued during that time.

"It's not enough money as it is. And then you break it down when you don't have access to it until you're in a lot of debt. You know and so all that ends up happening is you paying off part of the debt, not even the entire debt," Morgan said.

Morgan works as a barber, using techniques he learned in Angola: Rather than using the latest tools, he takes a razor blade and presses it up against a plastic comb, manually adjusting how far out the blade needs to be to complete the cut.

He currently rents a chair in a friend's barber shop, but he and another friend – and fellow exoneree – are hoping to save up and find a space of their own where they can run their own shop.

Morgan said that it's a "travesty" that 17 states have no state compensation laws, but added they could improve in other ways.

Beyond getting more money than the $250,000 over 10 years offered by Louisiana, he said, receiving a single windfall would be more helpful.

"It could have helped me not go into debt, maybe build up some credit to advance myself either further," he told ABC News. "It's just as simple as that. Once you go into debt, then the credit's messed up and you can't get help."

While a kindhearted explanation of why the money may be spread out is to avoid having the newly released exoneree be swindled out of it, Morgan said that the parsing out of the money is an example of the state intervening.

"Whatever they do with it, that's their business," he said, referring to recipients of compensation. "Even if they spend it in one day, that's their business."

Right now, Morgan said, he's "struggling to pay rent, struggling to keep my business open" -- a stark contrast to where he thought he would be in life by now if he hadn't been wrongly convicted.

"I feel I would at least have a home by now, at least two vehicles," Morgan said. "I'd be able to help my child, my son, my nieces and nephews, you know, have stuff saved up for when they get caught in a jam or help them out. I have none of that."

Though 16 years older, Alexander is in a similar situation, grasping for a safety net that isn't there.

Maw, who has represented both Alexander and Morgan, is involved in the effort to secure Alexander his state compensation, though it's not clear how long that will take. Because of the way Alexander's exoneration was reached, Maw explained that there are some evidentiary elements of his case that now need to be put into the legal record in order for the department that determines compensation to evaluate his compensation claim.

Alexander stressed that he's grateful –- to the legal team at the Innocence Project, to his wife and son, to have the chance to spend time with his grandson, to the strangers who donated to help him get a car -- but right now he's focused on "this second chance in life."

"Life is precious, and you only run the race one time. And most people try to make the most out of it ... but when that is taken away from you, when the opportunity to live is taken away from you it hurts. And it's taken away from you for something you didn't do, now that hurts even more," he said.

"I'm trying to put 38 years together in a few years, because eventually I'm going to reach the age where I'm not going to be able to work, if I live that long," he said. "And that's another big fear in my life -- and actually it's the largest fear of my life -- is being unable to provide once I reach that age and not able to work. The compensation would help that. Cause I've done 38 years' labor for two pennies."