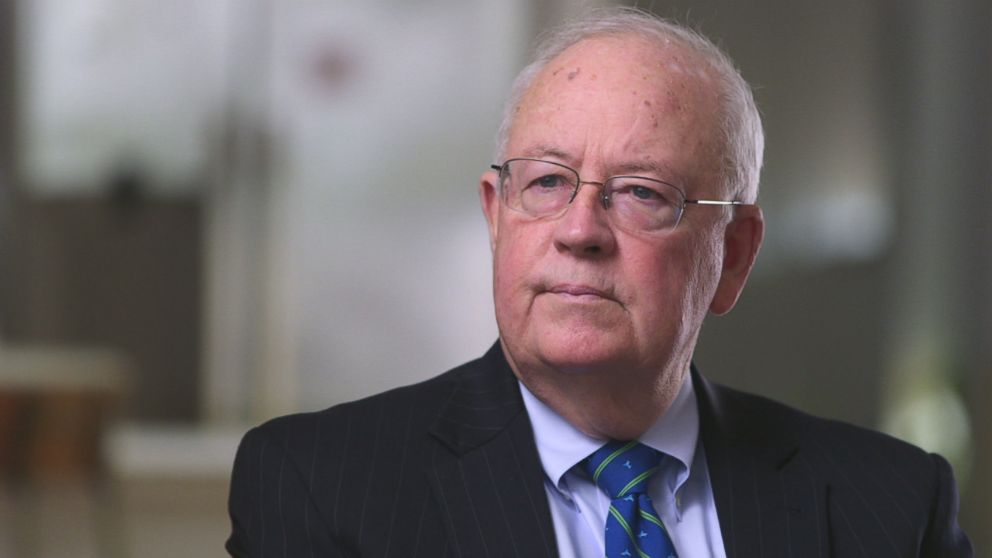

Kenneth Starr: Treatment of women involved in Lewinsky scandal 'American tragedy' of the 1990s

Starr said in the #MeToo era, accusers would have been less vilified.

Looking back on the impeachment of President Bill Clinton, Kenneth Starr, who served as the special independent counsel, said he doesn't think today, in the #MeToo era, Americans would have allowed the women who came forward back then to be vilified as they were in 1998.

"We live in a very different era, especially in terms of the way we treat human beings," Starr said. "The treatment that was afforded by the Clinton White House -- and by the president himself -- to women who had come into his orbit, into some kind of relationship with him ... to demean and to challenge and to attack them in these very mean-spirited ways was a part of, I think, the American tragedy that we experienced in the 1990s."

In December 1998, the House impeached Clinton for obstruction of justice and perjury after Starr and his team brought forth documents showing, among other allegations, that the commander in chief had lied under oath about a relationship with former White House intern Monica Lewinsky.

Clinton was later acquitted in the Senate.

Lewinsky's name, however, was dragged through the mud. She was referred to as a "slut" and "vixen" in the media, as Clinton and his camp tried to discredit her story.

Starr said Sydney Blumenthal, Clinton's aide and friend, had even testified to a grand jury investigating the relationship between Lewinsky and the president that Lewinsky was a stalker and that the president was trying to "respond to a stalker-type situation."

"These were all total fabrication. Total lies," Starr said.

But in today's shifting culture and national conversation around sexual harassment, consent and power, that treatment of Lewinsky and others likely would have been viewed differently by the public, according to Starr.

"I don't think that could happen again without there being a call to account," he told ABC News. "This kind of pattern of conduct, of the abuse of women, both verbally and otherwise, I think would be viewed now as unconscionable."

Starr gets Whitewater job

Starr had previously been named to the federal Court of Appeals by President Reagan and was a well-renowned conservative judge in Washington D.C. He'd also served as solicitor general under President George H.W. Bush. According to some, he was on the short list to become a Supreme Court justice.

In the early 1990s, however, he was given the independent counsel job in what became known as the Whitewater controversy. He was tasked with looking into allegations of fraud surrounding the Clintons and their associates' real-estate investments in Arkansas.

There were 14 criminal convictions related to the Whitewater case. The Clintons, who denied any wrongdoing, were not charged.

"I think the American people fail to appreciate the fact that there was significant criminality in Arkansas. ... It was simply too easy to accept the proposition -- that was demonstrably false -- that the investigation, in quote, 'found nothing in Arkansas' and then began investigating a personal relationship," Starr said.

In addition to the Whitewater-Arkansas probe, Starr's team eventually took on investigations into Bill Clinton.

The sexual harassment lawsuit brought against Clinton by Paula Corbin Jones eventually lead to what became known as "the Lewinsky scandal."

Bill Clinton is deposed

In 1991, Jones, an employee with the state of Arkansas, alleged that Clinton, then the state's governor, had sexually assaulted her in a hotel room. She filed a civil lawsuit accusing him of sexual harassment and civil rights violations.

In January 1998, Clinton was deposed in the Jones case and was asked whether he'd ever made any sexual advances toward her. Clinton said he had not.

He was also asked about other women who'd either alleged something involving him or had been alleged to have had some sort of encounter with him, including Lewinsky.

When he was asked whether he'd had a sexual relationship with Lewinsky, he denied it.

"His destiny was in his own hands," Starr said. "Bill Clinton should've settled the case. ... This entire attitude was one, I believe, of contempt for the rule of law."

Clinton later settled the Jones case but by then, Starr had taken up the Lewinsky investigation, thanks in part to information he'd received from her confidante, Linda Tripp.

Starr had reviewed Clinton's deposition in the Jones case and Tripp had provided him with secretly-taped phone calls between her and Lewinsky. Tripp claimed the former White House intern had asked her to lie under oath about what she knew about the president.

"We did some initial background investigating, listening to the tapes of the conversations between Monica and Linda. In those conversations, Monica was engaged in a criminal course of conduct. She made it clear she had filed a perjurious affidavit and she wanted Linda to do the same thing. And so Linda was being asked to participate in a crime, or to commit a crime," Starr said.

"She [Monica] is one of the most intriguing characters, as a human being, in the entire story and that's another part of the tragedy -- that it all could've been avoided if Bill Clinton had accepted his responsibilities to tell the truth," he said. "These kinds of cases embarrass everyone."

Later, Lewinsky would provide Starr with her infamous blue dress that bore Clinton's DNA, further corroborating what Starr and his team already knew: that Clinton had lied under oath about an affair with Lewinsky.

The Starr Report is released

Starr released the findings of his multiple investigations, including the one on Lewinsky, in September 1998. It was called the Starr Report. It was taken in 36 boxes to the House of Representatives but lawmakers posted the salacious report online.

The condensed version of the report became a New York Times bestseller.

Yet, the Starr Report was criticized for going into specific and lurid detail about sex acts between Clinton and Lewinsky that many argued weren't necessary or appropriate to prove the obstruction of justice case.

"It was supposed to be about obstruction of justice and perjury in a sexual-harassment lawsuit. But, what it seemed to be about instead was a piling up salacious details about sexual encounters," said Michael Isikoff, an investigative journalist.

Starr was the only witness brought before the House Judiciary Committee to testify in November 1998.

"I viewed the offenses as very, very serious," he told ABC News. "But, I understood the other side. ... I also understood because of my love of the Constitution and our system of government that we don't want to overturn elections in this country. ... Some jurisdictions of other countries have elections overturned and presidents sent off to prison. ... That's not our system."

The graphic nature of the report led to what many believed to be Starr's downfall. Instead of heading for the Supreme Court, Starr went on to pursue other opportunities. He did later became the president of Baylor University.

In his book titled "Contempt: A Memoir of the Clinton Investigation," Starr said that after the 1998 midterm elections, which gave the Democrats big wins and indicated to many that Americans still supported Clinton, there was a shared desire among some House lawmakers to find another way to punish the president with a fine or sanction.

"Maybe we could have found another way. ... I think all of those things were swirling around in the conversation that was had," he said.

Yet, Starr said, Americans chose to forgive Clinton and move forward, something that Starr thinks may provide insight for which direction the country may go in the future.

"That's one of the great things about the American people," he said. "I hope it will continue in this time of great rancor now in the age of Donald Trump, when people are really yelling and screaming at one another. ... We've been through some pretty tough patches as a people in trying to work our way through all of this. ... I'm such an optimist."

"The American people are very forgiving. I hope that we will recover our more Lincoln-esque side of 'with malice toward none and charity toward all,'" Starr said.