Chicago Teachers Union considering tentative agreement to end strike

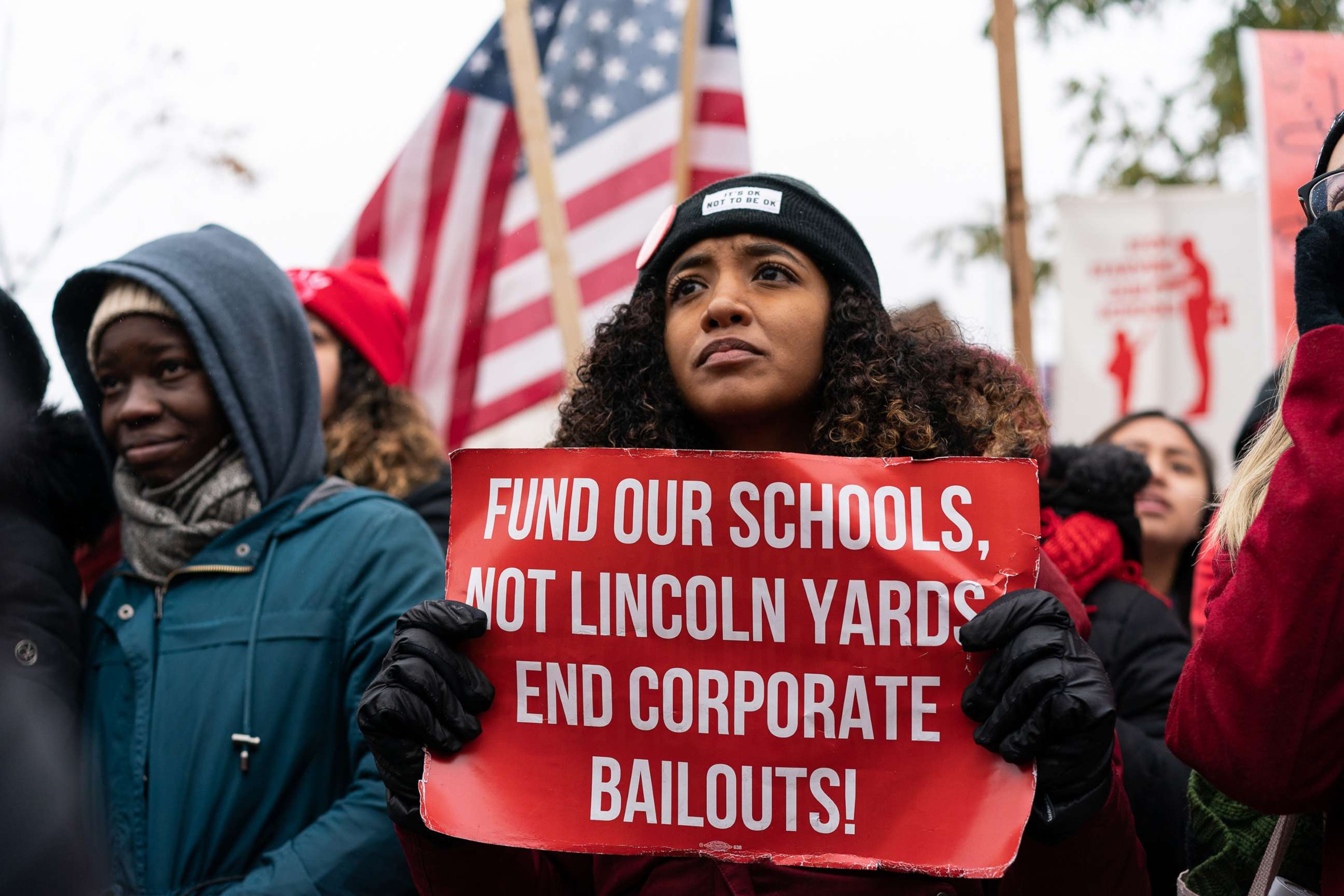

Teachers in Chicago walked out of classrooms on Oct. 17.

As more than 30,000 striking Chicago public school teachers and staff walked picket lines again on Wednesday, parents like Natasha Dunn said they're frustrated and stressed out over what the mounting missed school days will mean for their children.

But the Chicago Teachers Union released a statement late Wednesday saying they "may have reached a monumental agreement." The union is expected to present the tentative deal to its House of Delegates for consideration later that night.

Dunn's son, Jordan, a high school senior, and more than 300,000 Chicago students now have missed 10 days of school, leaving them and their parents hopeful that the union and city have reach a breakthrough agreement.

As the strike continued, Dunn said she and her son have fretted over how missing those days could affect his academic goals. Dunn said she's also worried about how her son has been biding his time away from the classroom.

"He's bored. I mean, he's sitting at home all day and so he's just like, 'I want to get out. I want to do something,'" Dunn said Wednesday on ABC News' "Start Here" podcast.

Adding to Dunn's anxiety is the ongoing gun violence in Chicago. Over the weekend, 24 people were shot in the city, three fatally, according to police.

"We stay on the South Side of Chicago. Not to say that it's bad all over, but as a black parent raising a teenager, I don't necessarily want him out and about because anything could happen," Dunn said.

Cooped up inside as his teachers and guidance counselors bargain to break the impasse, Dunn's son is trying to study for the Advanced Placement test for college.

"He's been working with teachers to pass it," Dunn said. "And now his concern has been, because he's been out of school for so long, that he's not going to meet those benchmarks that they are supposed to meet at certain times to get them ready for the AP exam."

She said she's been following the negotiations closely since the strike began at 12:01 a.m. on Oct. 17 and has been "confused" by the unions' demands.

The city's latest offer includes a 16% pay raise over five years and $35 million to reduce class sizes, $10 million more than earlier offered. The city also is offering 209 additional social worker positions by 2023 and 250 more nurses.

"I believe that to be fair. The CTU did not find that to be a fair offer," Dunn said. "By Oct. 17, CTU threw in affordable housing. As a parent, I was confused because it's my understanding that the only things that teachers are to strike over are wages and work conditions. But it became a bigger social issue."

She added: "It is the responsibility of both to come to an agreement, to think about the kids and put them first."

On Tuesday, Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot and CTU representatives blamed each other for the prolonged strike, now the city's longest teachers' strike in 30 years.

"We moved our position even further to where CTU said it was most critical to getting this deal done. What we heard is, it's still not good enough," Lightfoot said at a news conference. "What's prolonging this strike is union insistence on a shorter school day or school year, and insistence that I support their political agenda."

CTU Vice President Stacey Davis Gates accused the mayor of setting up an "unfair expectation" for the most recent negotiation session on Tuesday that failed to produce an agreement.

"We had a meeting where grownups got to ask questions. That's what this meeting was about," Gates told reporters, refuting rumors that union representatives walked out on the negotiations after raising hopes that a settlement was imminent.

"Let's get it right," Gates said. "You don't go on strike for this many days to come back and say 'I wish I would have ...'"

Lightfoot said Wednesday she's hopeful the union will soon vote to accept the city's latest proposal.

"I'm not surprised by the length of the strike. There's a lot of work that we could have done sooner, but we didn't start to do until the strike," said Lightfoot, who was elected in April.

"This has been a long journey," she said. "Unfortunately, I think there's a lot of harm that's been done to our young people. But my hope is that when the [union's] House of Delegates reconvenes today that there will be a robust presentation of the tentative agreement that's on the table and that they will vote on it up or down."

Under Illinois state law, school districts are required to plan a minimum 180-day calendar with at least 176 days of student instruction and five days designated for emergencies. School days canceled after Tuesday, the ninth day of missed classes since the strike began, will, under the law, have to be made up to meet the minimum class-calendar schedule, officials said.

Chicago public school officials could tack the days onto the end of the school year or subtract days from winter break or cancel other holidays to meet the state statute, officials said.

Union leaders said Lightfoot has agreed to allow students and teachers to make up lost days at the end of the year.

After hearing late Tuesday that classes would be canceled again, parents like Brenda Delgado, a mother of three children enrolled in Chicago public schools, scrambled to adjust their work schedules to take yet another day off to care for their children.

"We might be taking care of some other kids and some other friends might be taking care of kids, if this goes into next week," Delgado told ABC Chicago station WLS-TV. "I can't take too many days off of work, but I'm taking off (on Wednesday) for sure."

Like many parents, Delgado said she wants to turn her children's time away from the classroom into a teachable moment.

"They are going to learn civics. They're going to walk the picket line," Delgado said. "They're going to have their art class and make picket signs, and they're going to be creative to get their message across."