'A Killing on the Cape': The Murder of Christa Worthington -- Episode 3

The gruesome 2002 murder of Christa Worthington rocked a small Cape Cod town.

— -- An encore presentation of this "20/20" report will air on Friday, Dec. 28, 2018, at 9 p.m. ET on ABC.

This is Episode 3 of "A Killing on the Cape," a six-episode ABC Radio podcast and an ABC News "20/20" documentary. Watch the two-hour "20/20" documentary HERE

For Episodes 1 and 2, please visit http://abcnews.com/akillingonthecape.

Subscribe and listen to the podcast on our partners and platforms: Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Play Music, TuneIn, Stitcher and under the "Listen" tab on the ABC News app.

The "20/20" special presentation of "A Killing on the Cape" will air on Friday, Nov. 24, starting at 9 p.m. ET.

Episode 3: More Leads, More Dead Ends –

In the weeks following the gruesome murder of Christa Worthington, police had a laundry list of people they suspected of being involved.

Investigators had questioned Tony Jackett, the father of Worthington’s baby, and his wife, Susan Jackett, but were forced to turn their attention elsewhere.

Worthington, a 46-year-old fashion writer and single mother, was found stabbed to death in her home in Truro, Massachusetts, on Jan. 6, 2002, with her 2-and-a-half-year-old daughter by her side, unharmed. Her garbage man, Christopher McCowen, 45, was eventually convicted of raping and murdering her, but his defense attorney claims he is innocent and is currently working on getting McCowen a new trial.

Prosecutors believe they have the right man behind bars, but at the time, Worthington’s gruesome and mysterious murder was the highest profile case the Truro Police Department had seen in decades. The investigation put the entire Cape Cod town in the cross-hairs as public pressure on District Attorney Michael O’Keefe to solve the case grew.

Police didn’t officially rule out Tony Jackett as a suspect in Worthington’s murder for roughly three years after her death. Jackett had previously had an affair with Worthington that resulted in their daughter, Ava, who was born in May 1999, but Jackett had come clean to his wife, Susan Jackett, about the affair and the baby well before Worthington’s death. In fact, Susan Jackett said eventually she welcomed Worthington and Ava into their family – the Jacketts had six children -- and they would all have dinner together regularly.

But Tony Jackett wasn’t the only one who came under suspicion. Tim Arnold, another one of Worthington’s former lovers and the person who first found Worthington dead in her home at 50 Depot Road, became a suspect.

Arnold told police that he gone over to Worthington’s home with his father, Robert, around 4:30 p.m. on Jan. 6, 2002, to return a flashlight he had borrowed from her. That’s when he said he found Worthington dead on the floor. He ran back through the woods to call 911 from his father’s house next door because he said he couldn’t find a phone in Worthington’s house.

Tim Arnold has not done any interviews for years and declined ABC News’ requests for interviews for this story.

Maria Flook, the author of “Invisible Eden: A Story of Love and Murder on Cape Cod,” a book published in 2004 about Worthington’s life and career before her murder, and who had taught Worthington in a writing class, says she got to know Arnold after Worthington’s death and believes he really did love her.

“He was the first person I spoke to who knew Christa well because he had a relationship with Christa that lasted for a while and ended when they couldn’t work through their problems,” Flook said.

As she was putting together her book, Flook said she met with Arnold and asked him “direct questions about Christa,” including “the depths of his feelings for her.”

“He would say things like, ‘I can’t talk about that,’ ‘nope, not going to discuss that,’ because he was in great pain… over her death,” Flook said. “But I think he was also in pain because she rejected him.”

Flook described Arnold as a “very pleasant person” who was educated and a visual artist who had written a couple of books.“I think one reason Christa connected with Tim Arnold is that he was literary,” she said. “He wrote this book, ‘The Winter Mittens,’ which is a children’s book, but it’s a very strange little children’s book. It’s very dark.”

“The Winter Mittens,” which was published in 1988, is about a girl who finds a pair of old mittens that causes it to snow. At first, the children in the story are delighted, but then the snow grows into a blizzard and the girl is unable to take the mittens off.

Arnold met Worthington through a mutual friend and the two started dating in the fall of 1999 when Ava was a few months old and Worthington’s affair with Tony Jackett was over, according to what Arnold told police on the night he found Worthington’s body.

Arnold and Worthington dated for about a year. Arnold eventually moved into Worthington’s house at 50 Depot Road and became very close with Ava.

“He became somebody who helped Christa, he was a babysitter, but also helped her around the house,” Flook said. “Ava started to call him ‘Tim Mom,’ so he wasn’t just ‘Tim,’ he was ‘Tim Mom,’ because he was like another mother.”

But by then, fault lines in the relationship became to emerge. A growing issue was Arnold’s health problems, which included neurological and eyesight issues.

“They had an intense relationship that I think, at first, she depended on him because she was a single mother and he was very helpful to her, but I think that she saw that he had demands that frightened her,” Flook said. “His eye condition bothered her because she told him, ‘I worry you’re going to fall on my daughter,’ because he had trouble walking sometimes… he often had to cover one eye to be able to see clearly, otherwise he would see double.”

Flook said Worthington was “sort of difficult” with Arnold, and that he told her Worthington would criticize him for humming.

“She would say she didn’t want Ava to become ‘a hummer’ so he couldn’t even hum, which is something you do when you’re happy,” Flook said. “So in a way, it was like saying to him, ‘Don’t be happy around me, that’s not a way I want to teach my daughter.”

As Arnold and Worthington’s relationship began to deteriorate, the two ended up having arguments about a number of things, from their sex life to money. But according to an interview Massachusetts State Trooper Christopher Mason had with Arnold, their arguments never escalated to physical violence.

Arnold told police that Worthington would often be critical of him, but when their arguments would boil over or reach a stalemate, he would end up walking away.

He also told police that there wasn’t a specific incident that drove him to finally move out of Worthington’s house, but that he had thought about it a number of times and after finally growing tired of constant arguing, he packed his things and moved back in with his father in the fall of 2000. Arnold’s father’s house, which was about 100 yards from Worthington’s, is the same place Arnold called 911 from the night he found Worthington’s body.

But even though they broke up, Arnold told police he stuck around so he could stay involved in Ava’s life. Though police said he also acknowledged that he still harbored feelings for Worthington and had, in part, hoped that he would be able to rekindle their relationship.

“He felt rejected and he felt stymied,” said author Peter Manso, who wrote a book about Worthington’s murder called, “Reasonable Doubt: The Fashion Writer, Cape Cod and the Trial of Chris McCowen,” and was a consultant for ABC News on this story. “After she threw him out of her bed, he continued to volunteer to babysit for her, while she went to the movies with this one or went to a dinner over here.”

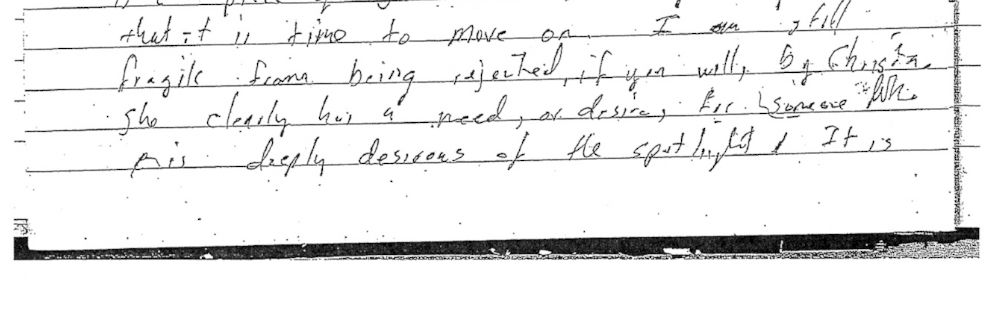

In Arnold’s diary, he wrote about Worthington, about making plans with her and expecting that she would call and cancel on him. At another time, he wrote that he was fragile from being rejected by her and questioned why he allowed himself to get into this situation when, as he wrote, “I should have seen her [lack of] intentions from the start.”

Despite the uneasiness, Arnold tried to remain part of Worthington and Ava’s lives for more than a year after they broke up. But their troubled relationship history didn’t make him look good to police.

After Arnold found Worthington’s body, Flook said the police took him to the station for questioning, but it seemed even his own father, Robert Arnold, who had driven him over to Worthington’s home to return the flashlight, had wondered if it was possible that his son had killed her.

When Tim walked into the house after talking with police, Robert Arnold was sitting in front of the TV, waiting for him.

“I was very shocked when Tim told me that his father said to him, ‘Tim, did you do it?’ His own father asked him that,” Flook said. “From that moment on, the whole town was asking questions like that.”

Police interviewed Arnold a number of times in the first year or so after Worthington’s death. In his first interview, he told police on the day he found Worthington’s body, Jan. 6, 2002, he had been house-sitting in Wellfleet, another Cape Cod town not far from Truro.

He told police the house he was staying at didn’t have a clothes dryer and he had been doing laundry, so he asked his father to come pick him up so he could dry his clothes at his father’s house. Tim Arnold had undergone brain surgery in the spring of 2001, about eight months before Worthington’s death, and coupled with his double-vision problem, he couldn’t drive, which is why he said he asked his father to come pick him up.

Once he got to his father’s house, Arnold told police he was finishing laundry and the two of them were both watching the Patriots game. At some point, he called Worthington because – as he later told police -- he had made tentative plans to have dinner with her that night. So he called Worthington to check on their plans, but got no answer and left a message.

When the Patriots’ game ended, Arnold’s father was about to drive him back to the house in Wellfleet and on the way, Robert Arnold suggested they return Worthington’s flashlight that Tim had borrowed a few days earlier. That’s when Tim Arnold said he found Worthington.

Police had interviewed Arnold on the night he found Worthington, and then again three days later on Jan. 9, 2002, but then five months went by before they interviewed him a third time in June 2002.

In that time span, investigators were still taking a hard look at Arnold. They had subpoenaed his phone records, they had checked with cab companies to see if he had possibly used one to get to Worthington’s house over the weekend when he said he was in Wellfleet. They also began zeroing in on the arguments he said he and Worthington had during their relationship, something they asked him about when they met with Arnold on June 13, 2002.

During that interview, Trooper Mason also pressed Arnold on some voice messages they had found on Worthington’s answering machine.

A sampling of voicemails Tim Arnold left for Christa Worthington

One of Arnold’s voicemails to Worthington said: “Hi, I think I’m going to head back over to Wellfleet. I don’t feel particularly comfortable here with this non-stop stream of stuff, not that it matters much, but hope you had a nice day. Bye.”

Another voicemail from Arnold: “Hi, Sunday morning around 8. Would you like to have coffee? Are you around? I thought you would be up. I’m sorry if you’re not.”

This voicemail: “Hi Christa, what’s up with the movie, is that a problem? Did I call too early? I get the feeling that this is one of those things where you say you’ll call back and you’re not going to and I’m wondering what this is all about, if anything. So, give me a call, if you can, would you? Thanks.”

And this one: “Well, I think you’ve made it clear where you stand on the issue of friendship so, I—at this point, don’t expect me to be around.”

And this one: “Hi Christa, just to clarify, if you wanted to call to try to arrange for a time for me to try and see Ava, that would be fine. I’ll see what I can do. But, I don’t think that we should really see each other, even briefly. Bye.”

In the third report, Trooper Mason wrote, “At first Arnold stated that he was satisfied with being friends. Arnold later admitted that part of his interest in visiting Ava was that it provided him with an opportunity to see Christa.” Mason’s report concluded with noting that investigators asked Arnold for his diaries and his computer, which he turned over to state police Sgt. William Burke.

Mason’s report also said that Arnold later called Sgt. Burke to tell him about an incident in which he stopped by Worthington’s house unannounced – something he said he had been asked by Worthington not to do – and that she saw him “peering in through the window.” Arnold told Burke that he had looked in the window because he had knocked on the door and there wasn’t an answer. He told Burke that Worthington was upset with him over that and added that if police were to find his fingerprints outside Worthington’s bedroom, “that would be the reason.”

Three days after his third interview with police, Arnold decided to hire a lawyer – Russell Redgate, who has been on Cape Cod for 30 years.

“The main job I had when I met Tim was just to protect his rights,” Redgate said. “And I begin with, in June, the month I met him, with a letter to the D.A.’s office, just to say that after talking with my client… we’re going to decline the [police] interview that was set up but he [Arnold] wants to cooperate and further interviews are possible, it’s just that I have to be involved in arraigning the circumstances, setting the ground rules.”

For the next six months after that, there appeared to be no communication between police and Tim Arnold until Jan. 13, 2003 – just over a year after he found Worthington’s body.

Mason wrote a report that day that said Arnold has called him at his office and was upset that they had not cleared him from being involved in Worthington’s murder.

“Tim had heard that he was the chief suspect and despite my advice, he called up Chris Mason and he asked him, he said, ‘I’ve heard that I’m the chief suspect.’ Chris Mason told him, ‘Yes, you are,’” Redgate said. “That was very upsetting.”

Redgate said his client “certainly had a sense” that he was under suspicion, but learning he was the investigators’ chief suspect at the time “alarmed him,” so much so that by the next day, Redgate said Arnold was in the hospital.

“He was very upset about a lot of things at that time, mainly the case, but he was upset and may not be thinking as clearly as he should have,” Redgate said. “I know that his psychologist was concerned that he needed help… she decided that it would be best if he went to Cape Cod Hospital emergency room.”

Redgate said Arnold was admitted to the psychiatric wing of the hospital and he later learned, “the police interviewed him.”

Mason and Burke had gone to visit Arnold at the psychiatric wing of the hospital he had checked himself into the day after Arnold had asked Mason if he was a suspect. There, Redgate said they questioned him again about the last time he spoke to Worthington, and he said the accusations were direct.

“They’re police and there’s two of them, you know, you get a jab from one side and then a right hook from the other, you know, there were rough… verbally,” Redgate said. “You can see from Tim’s testimony when he described that, he said that more than once, he would say something like, ‘I had not killed Christa,’ and he said they would come right back and say, ‘Oh, yes you did.’”

During the hospital encounter, according to police reports, Mason told Arnold that he had heard about a fight in which Arnold tried to break down the kitchen door -- the same door that was apparently kicked in at the crime scene. Arnold told Mason that he and Worthington had been arguing one day and he had left. When he came back, Arnold said Worthington slammed the door and locked the deadbolt, and he said there “may have been” some pushing on the door, but that it wasn’t broken down.

“Tim said that they accused him once of barging into her kitchen, that she complained that he barged into her kitchen,” Flook said. “This is a man that lived in that house and he had an argument brewing with her. He probably, in anger, just barged in.

“It’s that kitchen barging scene that people like to talk about, but I don’t think it was anything,” she added.

Mason and Burke told Arnold that his statements and actions were “consistent with someone that was involved in the murder” and told him that if he was involved, he needed to tell them the truth. Arnold again denied any involvement, then said he wanted his lawyer and the interview ended.

“The two detectives that went the hospital… I know them both,” Redgate said. “As much as I could criticize many things about the way they did things, what troubled me the most was that they had received a copy of my letter saying, ‘we’re not going to give any interviews, they have to arranged through me.’”

Redgate said he heard about the hospital interview a few days after it happened and called District Attorney Michael O’Keefe, who is still the district attorney for the Cape and Islands district today.

“We talked and he was emphatic that the police got nothing, and of course if they had, I think it would have been subject to suppression,” Redgate said. “I was pretty confident of that, but Michael said they didn’t get anything. Tim just said nothing that could hurt him.”

With Arnold not cracking under the pressure and his health problems affecting his mobility and vision, investigators started to doubt his involvement in the crime. But Worthington’s past lovers weren’t the only focus for police early on in the investigation.

As police looked at those closest to Worthington, their investigation came to include Worthington’s father, Christopher “Toppy” Worthington, and his girlfriend, Elizabeth Porter.

Toppy Worthington, then 72, was a Harvard-educated lawyer and former prominent government official. Porter, 29, was a former prostitute and heroin addict.

Christa Worthington had apparently been quite upset about the relationship, and in the days after his daughter’s murder, Toppy Worthington’s relationship with Porter made headlines.

Before speaking with Porter about the case, police first questioned Toppy Worthington. He was notified about the murder on the night his daughter’s body was found and went to Christa’s uncle John Worthington’s house, where the rest of the Worthington family had gathered, at about 9 p.m. on Jan. 6, 2002.

As Sgt. Burke was telling Toppy about what had happened to Christa, Toppy asked questions that seemed to grab their attention.At one point, Toppy interrupted Burke to ask “if his daughter was on her back and if there was a lot of blood with injury to the right side of her head,” according to the police report.

Police wanted to know how Toppy was aware Christa was on her back and that there were cuts and bruises on her face, including swelling on her right eye. But when Burke asked Toppy if anyone had told him about what happened to Christa, Toppy said no and that he was just trying to figure out if the person who did it was “right or left handed.”

However, what caught investigators’ attention the most was Toppy’s relationship with Elizabeth Porter. The day after Christa’s body was found, they asked Toppy whether he was seeing anyone. Toppy said he was, but refused to give them Porter’s name.

In Burke’s report of their conversation, Toppy said his girlfriend had “trouble in the past” and that’s why he didn’t want to give them her name, but told them that if they wanted it, “I’m sure you’ll find it.”

Porter had been linked to another murder case just a few years earlier. She testified before a grand jury that she met a man named Dirk Greineder while working for an escort service in 1998.

Greineder was a Massachusetts doctor who was sentenced to life in prison for killing his wife in 1999. The prosecution said Greineder had killed his wife after she became aware of his extramarital activities – which had included Porter.

Even though Toppy Worthington didn’t give Porter’s name, it didn’t take police long to find her. By Jan. 9, 2002, three days after Christa’s body was found, investigators had their first interview with Porter.

According to police reports, she told them that Toppy was her boyfriend and that she had met him while she worked for an escort service in 1998.

Police asked her if Toppy had been giving her money, and even though she was reluctant at first, Porter eventually told them that Toppy had been giving her a few hundred dollars a week in spending money, as well as paying for her apartment and utilities.

As news reports would later show, Porter’s landlord was under a completely different impression of the relationship between Toppy and her. The landlord told ABC’s Boston affiliate WCVB-TV at the time that they thought Porter was Toppy’s stepdaughter.

Police eventually learned from Christa Worthington’s friends and acquaintances in the days after her death that her father’s relationship with Porter and the money he was spending on her had become a major concern for Christa.

In interviews with police, Toppy said he was at his home asleep at the time when police believe Christa Worthington was killed, which was sometime in the overnight hours of Friday, Jan. 4, 2002, into the early morning hours of Saturday, Jan. 5, 2002.

Porter told police that she was at her apartment alone then, but police learned within a few days of speaking with her that she was with a former boyfriend of hers -- a fellow heroin addict-- who happened to call in sick to work overnight that Friday into Saturday.

When she first spoke to police, Porter said she hadn’t seen the former boyfriend, Eddie Hall, in a few months. But police came to find out that Hall had actually been living with Porter for the last year or so at the apartment Toppy was paying for.

According to police reports, Hall told investigators that on the night police believe Christa Worthington was killed, he had gotten too high to go to work and called in sick for his 10 p.m. to 6 a.m. shift. He said he then spent the night in the apartment with Porter.

Police asked Hall and Porter in separate interviews about what they would do if the money from Toppy ran out. Hall answered that they would have to get clean and find jobs, while Porter told police she wasn’t concerned about it.

But police were trying to find out if Christa Worthington’s own attempts to prevent Porter from getting any more money from Toppy had driven Hall and Porter to kill.

“She went crazy over this thing. She screamed at her father. She wrote letters to the lawyers. She got her own lawyer. She wanted this stopped,” author Peter Manso said.

Eli Gottlieb, a writer and novelist who was Worthington’s former coworker at ELLE magazine, told ABC News that the “girlfriend was basically spending down Christa’s inheritance. She was watching her future share of the estate go away. It’s not impossible to think that the father’s girlfriend had something to do with Christa’s murder at least at the very beginning… because Christa was getting in the way.”

In one police report, Hall told them that Porter had once said that she wished Worthington was dead after Toppy had told her that Christa was upset with how much money he was spending on Porter, so he’d have to cut back. Hall added that after Worthington’s death, Porter said she felt bad for saying that.

Police asked Hall if he had anything to do with Christa’s death, and he replied, “Hell no.” Hall said Porter couldn’t have done it either since she had been with him that weekend.

Toppy, Porter and Hall all agreed to take polygraph tests. Toppy and Porter failed their tests, while Hall’s results were inconclusive.The trooper who administered Toppy’s test wrote that Toppy was deceptive and showed “significant responses” to the question: “Did you plan with anyone to harm Christa?”

Porter’s report said she showed deception and significant responses to the questions: “Did you stab Christa in that house?” and “Did you plan with anyone to harm Christa?”

When police came to speak to Porter about her polygraph test and told her that she failed, Trooper Mason wrote in his report that Porter became emotional and claimed she was “dope sick” and so her results were invalid. Mason wrote that Porter told them that she would cooperate in any way to prove her innocence and offered to give hair samples, DNA samples and fingerprints if necessary.

But there was one key piece of evidence that would clear Porter, Hall, Tim Arnold and every potential suspect police had focused on thus far: DNA from an unknown male found inside and on Christa Worthington’s body.

Investigators had found saliva and semen on Worthington that matched one person, but at that point in the case, they hadn’t been able to identify him.

Police had found Tim Arnold’s DNA on a brown blanket that had been thrown over Worthington’s body the night she was found, but since Arnold had previously lived in the house with her, authorities didn’t find it that significant.

Neither Arnold, Hall nor Tony Jackett’s DNA matched the saliva and semen sample found. In fact, police took DNA samples from no less than 25 people in the first year after Worthington’s murder, but of those 25, no one matched the DNA found on her body.

In an effort to find out who last had sex with Worthington, police took their most unorthodox step yet –asking every male in the community to submit DNA samples.

By then, it was early 2005, and investigators stood in front of businesses in the town of Truro and asked men to voluntarily give up their DNA. It was the move that pushed the case into the national spotlight.

“It’s a very controversial thing to do because you’re really asking people – and it has to be voluntary – to give up their DNA, so you’re basically saying, ‘My entire community is a suspect,” said Brad Garrett, a former FBI profilers and ABC News consultant.

When authorities announced the DNA dragnet, Trooper Mason defended the move at a press conference, saying at the time that “from an investigative standpoint, it is efficient and it is effective.”

“It allows us to couple an assertion that, ‘I was not the donor of that DNA, that I do not know Christa Worthington,’ with forensic evidence that supports that assertion,” Mason said.

One of the places investigators stood outside of to collect samples was the Truro post office. There is no mail delivery in Truro so people have to come to the post office to pick it up.

The town’s residents had mixed reactions to the DNA sweep.

“It clearly circumvents my civil right to privacy,” one resident told WCVB-TV at the time. He was so outraged by the idea, he called the American Civil Liberties Union, which then asked District Attorney Michael O’Keefe to stop collecting samples.

In response, O’Keefe told our affiliate WCVB-TV at the time, “We certainly will be compelled to look at that and the reasons why they may not, and there may be good reasons why.”

Author Pete Manso said he felt the move was “a form of coercion.”

“Truro men… were told you don’t have to give us your DNA but if you don’t, your name is being put on a list and you will be scrutinized,” he said.

The DNA sweep resulted in the collection of between 150 and 200 samples, according to Mason, drawing criticism about the possibility of flooding the state crime lab with DNA swabs and causing a back log of untested evidence.

In April 2005, two months after the DNA sweep, investigators met with the state crime lab to discuss how they should prioritize the samples for testing. But instead of tediously sorting through the samples deciding who to test first, investigators got the break they had been looking for.

On April 7, 2005, more than three years after Worthington’s death, the state crime lab told Mason that they had gotten a DNA match for the semen found inside Worthington.

Turned out, it came from a DNA sample given to investigators more than a year prior. Within a week, police made an arrest.

“When an arrest was made, we were stunned,” said former WCVB-TV reporter Amalia Barreda. “Especially since the person who was arrested was not anybody we had ever heard of.”

This article is part of an investigative series by "20/20" and ABC Radio looking into the murder of Christa Worthington and the trial and conviction of Christopher McCowen. Watch the two-hour "20/20" documentary, "A Killing on the Cape," HERE and the six-part podcast can be heard on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Google Play Music, TuneIn, Stitcher and under the "Listen" tab on the ABC News app.