'My life as a hater': The dire warning from a white power leader's son

With hate on the rise, the self-admitted ex-racist says it's time to speak out.

Driving through a recent morning rain in the mountains of West Virginia, 60-year-old Kelvin Pierce grew nervous as he approached a gate in the middle of a mud-caked dirt road.

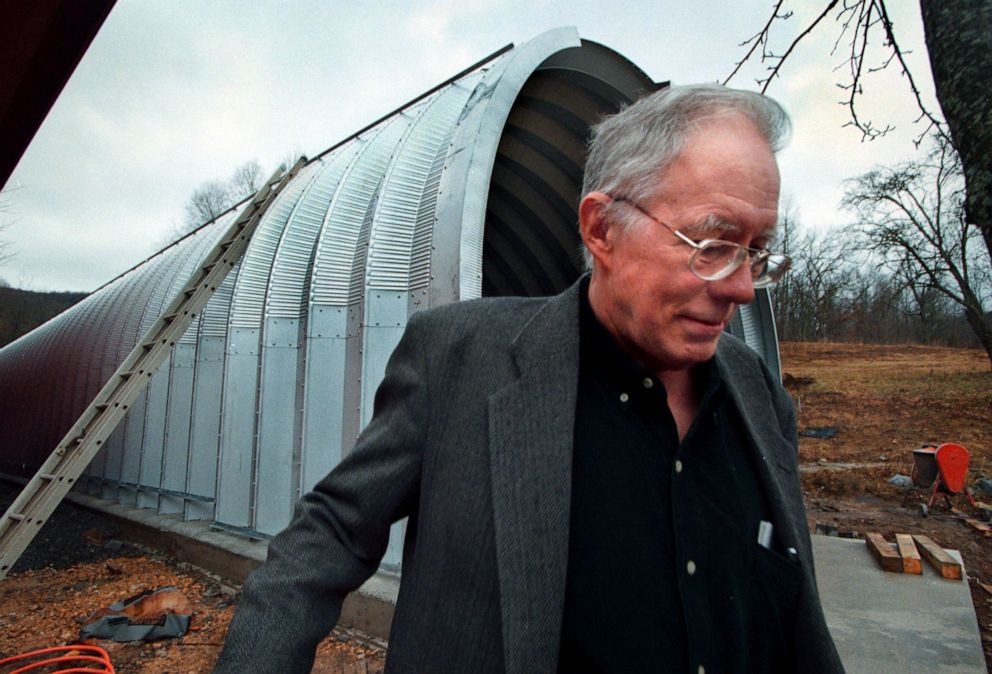

He had been there before, but that was nearly 20 years ago, when the compound beyond the gate headquartered what the FBI considered one of the most prolific and powerful white supremacist groups in America, the National Alliance – an organization led by his own father, Dr. William Luther Pierce.

“To be honest, I have an awful lot of stuff going through my mind as I think about going up to this property,” Pierce confessed to an ABC News team, which accompanied him on the trip.

His father had purchased the sprawling 350-acre property in 1985, hoping that many Americans would “flock” to his “whites-only enclave,” and that the property would help kickstart the “cleansing of America, as he saw it,” according to Pierce. From Pierce's perspective, William Luther Pierce and his followers had two goals: to turn all of America into a "white-only homeland," and to violently overthrow the U.S. government in the name of white nationalism.

Though Pierce’s father died in 2002 and the National Alliance’s position in the white power movement has since faded, the hatred and bigotry behind it all have not. In fact, counterterrorism officials warn that, after years of decline, hate groups are once again proliferating inside the United States – an unnerving reality mirrored by what Pierce saw that rainy morning on the West Virginia compound.

“It sat derelict for years, but now they have people working on the property, and they're kind of trying to bring it back to life,” Pierce said.

When Pierce first negotiated for permission to tour the property, the new head of the National Alliance, Will Williams, even told Pierce: “Everybody thought we were down and out. But we're back. … We are definitely back,” Pierce recalled Williams saying.

Pierce is now racing to stop what he called the “illness” of hatred from spreading even more. That’s why he brought ABC News with him to West Virginia, opening up about his own racist past, the personal demons that fueled his hate, and the struggle he endured to defeat them.

“There's hope that is engendered by a story like [mine],” he said. “If I could overcome that hatred, and that depression, and that feeling of unworthiness, then maybe somebody else could too.”

Born into bigotry

Pierce was raised to be a bigot.

Like so many other American children, when he was young he often dreamed of visiting the nation’s capital – but his dreams were far different than those of most kids.

“I remember fantasizing about going into Washington, D.C., standing on a street corner holding a machine gun, and mowing down Black people with that machine gun,” Pierce told ABC News in his first TV interview. “I used to actually fantasize about doing that.”

When Pierce was nine, his father implemented a new rule for playtime at the community swimming pool: “If a Black person came and got into the pool, we had to leave,” Pierce said.

In high school, his father barred him from playing team sports because, Pierce remembers his father telling him, “You have to shower with Blacks” – “And he didn’t use the word ‘Blacks.’"

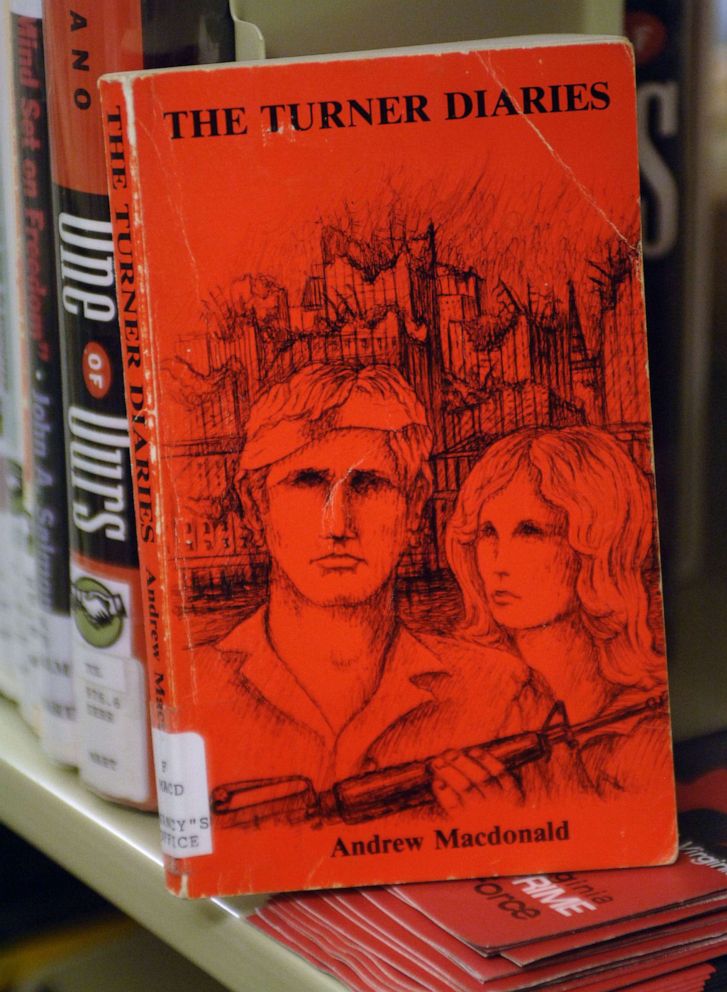

When Pierce was in college, his father published the novel “The Turner Diaries,” which experts describe as the white power movement’s “bible” with its depictions of a violent campaign against the U.S. government and a global race war that leads to the eradication of Jews, Black people and other non-whites.

“They were direct reflections of fantasies that he had, about actions that he wished he could carry out himself,” Pierce said of the stories in the book.

Then, when Pierce was in his 20s, his father purchased the West Virginia property, which helped cement the elder Pierce as one of the most influential white supremacists in modern history.

Even Timothy McVeigh, the nation’s most ruthless domestic terrorist, was a follower.

Before authorities caught up with McVeigh in 1995 for bombing the federal building in Oklahoma City, McVeigh called the National Alliance three times “to see if they had any safe havens,” McVeigh said in rarely-heard audiotapes obtained by ABC News.

And when authorities arrested him, they found highlighted excerpts of “The Turner Diaries” in his car. He had bought the book “in bulk,” he said.

Pierce said he’s sure his father “absolutely” approved of the Oklahoma City bombing, which killed 168 people – including 19 children in a daycare center – and injured nearly 700 others.

“He would say that, you know, ‘These are unfortunate results of what needs to happen for us to accomplish our goals,’” according to Pierce.

Who 'planted that seed' of extremism

Even today, Pierce said he isn’t quite sure who first “planted that seed” of extremist ideology in his father.

“But once that seed was planted, he made a decision to germinate that seed, to nourish that seed and to grow that hatred,” Pierce said.

What Pierce does know is that his father was a “very intelligent man” with a PhD in physics, who became somewhat lost professionally – that’s when his father began voraciously consuming racist literature and books such as Adolf Hitler’s “Mein Kampf,” Pierce said during hours of interviews.

That’s also when his father stopped paying attention to his children – unless he was angrily beating them for some perceived infraction, Pierce said.

“The only thing that was important to him was furthering his cause, and to bring about the revolution that he desperately hoped was going to happen,” Pierce said.

‘My life as a hater’

Despite how his father treated him – or precisely because of it – Pierce couldn’t help but feel drawn to his father’s racist ideologies.

“I believed a lot of the stuff that [my dad] taught me,” Pierce recalled. “I wanted him to acknowledge me. I wanted him to be proud of me. I wanted him to love me.”

Pierce recounted how in one high school history class, he wrote a paper “on the virtues of Adolf Hitler.”

“It was my futile effort to try to impress him,” according to Pierce, noting that he subsequently “spent a good portion of my life as a hater.”

Looking back on his life, Pierce now believes that he began questioning his own racist beliefs even as far back as college.

For the first time, as a student at Virginia Tech in Blacksburg, Va., he was “starting to experience people from all over the world … people from every kind of race and religion that you can think of,” he said.

But it would take him another two decades to really dig into what had driven him to so much hate.

He said he had been feeling depressed – even worthless – for “a long, long time,” so around 2004 he sought help: “Therapy. Counseling. Spiritual studies. A lot of reading.”

“And that's when I started this journey of challenging my thoughts and adopting a more spiritual worldview, and look at human beings,” he said. "I learned that I did not need to attach myself and my self worth to all of the fearful and hateful thoughts … That I could choose different thoughts. That I could reach out for better feeling thoughts.”

Those who spread hate “ultimately, deep down, whether they consciously recognize it or not, don't feel good about themselves,” he added.

According to Pierce, hate is like a drug: “You take a drug to feel better, but you end up feeling worse in the long run.”

Now what helps Pierce feel better is his work as a contractor and time with his wife and two children.

‘A pivotal moment’

In the years after Barack Obama was elected the nation’s first Black president, Pierce “got lulled into the belief” that racism in America “was getting better," he said.

But, according to Pierce, that belief "changed dramatically during the 2016 election cycle,” when he heard the inflammatory rhetoric that was being used by at least one major-party nominee for president.

And then, in August 2017, there was what Pierce described as “a pivotal moment for me,” when white supremacists from across the country gathered in Charlottesville, Va., in a violent rally that showcased how widespread ethnic and racial hatred had become in modern America.

“Watching those people march, and carrying those torches, and singing … that, ‘You will not replace us,’ that immediately transported me back to my childhood, and to my father, and to everything that he believed in and everything that he was trying to accomplish,” Pierce said.

One woman was killed during clashes at the rally, and President Donald Trump’s subsequent claim days later that there were “very fine people on both sides” of the rally alarmed Pierce.

By “using division as a tool to gain and to hold onto power,” the Trump administration is “now making outward expressions of hatred in our country unassailable,” according to Pierce. Trump has denied such accusations, insisting his rhetoric only "brings people together."

But for Pierce it's clear "a monster that went into hibernation," as he put it, "has come out of hibernation.”

That is why Pierce is now speaking out.

“I was like, ‘Okay, if there is some thing I can do to counter this, then I have to do it,” he said. “There is no time better than right now to speak up and let other people know that if there's any chance, any part of their fiber, that doesn't like the way they're feeling, doesn't like being in hatred, [they can] chart a path in a different direction.”

'Our enemies are rabid'

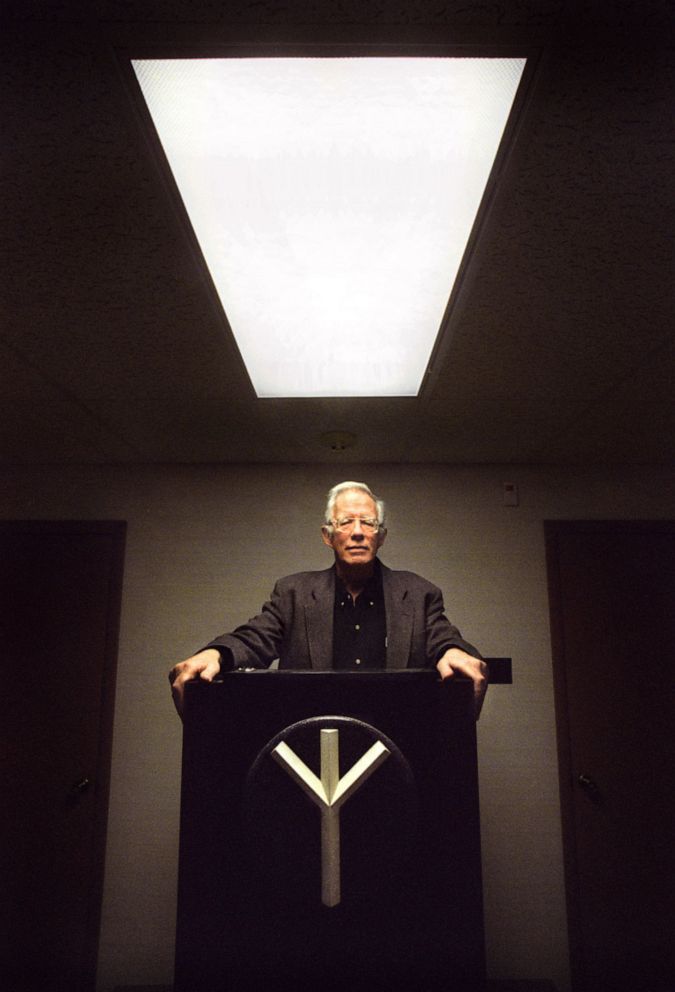

On that rainy morning on a West Virginia hilltop, the different path Pierce charted was evident as he walked around his father's former compound: He caught glimpses of his father's book, symbols of hate in windows, and the large National Alliance logo fastened to the front of the property's religious center decades ago.

According to the Southern Poverty Law Center, the National Alliance is now one of nearly 70 hate groups operating inside the United States.

“We in the National Alliance believe that our race is worth preserving,” Williams, the group’s chairman, told ABC News, even as he claimed the group no longer wants America to become a whites-only country and that it rejects violence.

“[W]e, as racial separatists, simply advocate geographic separation of the races by whatever means it takes. Many whites will choose to continue living in a multi-racial society. That's all right."

Asked whether their efforts could spark violence, Williams said: "Hopefully not. We would like peaceful separation."

"But it's not going to be peaceful," he warned. "Our enemies are rabid."

Pierce said the current state of the white power movement means there has been "a pretty massive swing of the pendulum in the wrong direction."

He still strongly believes, however, that "the pendulum is going to swing back in the other direction."

"Have a little hope," he said.

ABC News' Megan Christie, Alexandra Myers and Emily Ruchalski contributed to this report.