'The Longest Shadow': A radical post-9/11 government overhaul pits security against liberty

ABC News airs a five-part documentary series on the 9/11 attacks, Sept. 6-10.

The sky was clear and blue. The gray towers stood, both guarding and welcoming, at the gateway to the nation. Out of nowhere came the impact, the blaze, the smoke -- and then the towers were gone. When the dust and flames finally cleared, a new world had emerged.

The death and destruction defined that late summer day and remain seared in the minds of those who lived through Sept. 11, 2001. From the ashes and wreckage rose a new America: a society redefined by its scars and marked by a new wartime reality -- a shadow darkened even more in recent days by the resurgence of fundamentalist Islamist rule in the far-off land that hatched the attacks.

Twenty years later -- with more than 70 million Americans born since the crucible of the attacks -- the legacy of 9/11 remains. From airport security to civilian policing to the most casual parts of daily life, it would be nearly impossible to identify something that remains untouched and unaffected by those terrifying hours in 2001.

This week, ABC News revisits the 9/11 attacks and unwinds their aftermath, taking a deep look at the America born in the wake of destruction. "9/11 Twenty Years Later: The Longest Shadow" is a five-part documentary series narrated by George Stephanopoulos. Episodes will air on ABC News Live each night leading up to the 20th anniversary of the attacks, from Sept. 6-10. The series will be rebroadcast in full following the commemoration ceremonies on Saturday, Sept. 11.

Part 2: Is peace of mind worth the price?

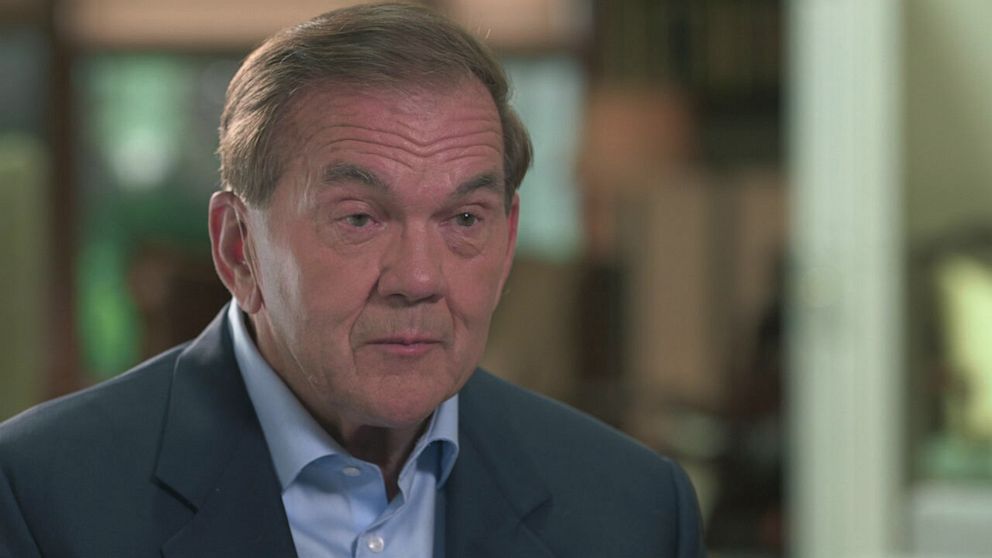

Tom Ridge set down his gardening tools and followed the state troopers inside his home on a cul-de-sac in Erie, Pa.

"It was a beautiful day -- hardly a cloud in the sky," recalled Ridge, who was then a popular two-term governor of Pennsylvania. "Things were going normally until four commercial aircraft struck."

"It was an attack."

Within hours, Ridge was in Shanksville, Pa., observing the wreckage of Flight 93 and comforting members of the small Western Pennsylvania community who were thrust into the first minutes of the Global War on Terror as the Twin Towers crumbled and the Pentagon burned. Two weeks later, Ridge was in the West Wing of the White House, serving as a security adviser to President George W. Bush. In 2003, he was sworn in as the first secretary of homeland security.

"And frankly, the criticism at the time was spot on," Ridge said. "'What does Tom Ridge know about terrorism?' Probably, like 99.999% of the rest of America -- maybe the rest of the world -- not too much."

In the wake of 9/11, as Americans grappled with the consequences of an unparalleled terror attack, the federal government scrambled to preempt a second wave of assaults that was feared to be imminent. The scale of the federal government's response to 9/11 matched the scale of tragedy it caused. And when al-Qaeda discarded the old rules of war, the Bush administration decided a new rulebook had to be written.

America's national security apparatus recalibrated the balance between individual liberty and collective safety. New agencies -- notably the Department of Homeland Security and its Transportation Security Administration -- were built from the ground up.

The challenges were monumental; the outcomes controversial. But for many who were there at the beginning, the ends justified the means.

"The American public, I can 100% assure you, are far, far safer today crawling onto an airplane than you were any time before 9/11," said Frank Hatfield, who oversaw the East Coast air space when al-Qaeda carried out its plan. He would go on to build the Federal Aviation Administration security operations system and lead it for most of the 20 years following Sept. 11.

When 19 hijackers boarded four California-bound airplanes on that calm late summer morning, their route through the airport terminals looked far different than it would today. No discarding liquids, no removing shoes, and certainly no high-tech X-rays and body scanners.

"You could have people meet you at the gate, you could have people go in with you, and you could have all kinds of things that you can't do now," recalled Margot Bester, a senior attorney at the TSA for most of the 20 years the agency has been in existence.

"Before 9/11 ... all the security screeners were contracted by the airlines," said Bester, who recently retired as the TSA's principal deputy chief counsel, the agency's number-two lawyer. "There were no really strong standards. So all of those hijackers got through, even with box cutters. They just got through, and I think that was a real shock to the country."

Those tasked with securing air travel describe the chaos of setting up a brand-new safety infrastructure while preventing another attack from taking place. For the TSA, a team of seasoned government officials set to work "standing up this agency from scratch," Bester said -- "no paper, no pens, no pads. We were bringing everything in from home."

"It was the Wild West," she said. "We're doing all of this, setting up an agency, at the same time that we're receiving all kinds of intelligence that aviation is still being threatened ... all of this is happening simultaneously."

The new security mechanisms were a success in some critical ways. John Farmer, senior counsel to the 9/11 Commission, notes that "there has not been another major terrorist attack in the U.S with casualties on the scale of 9/11."

But no security overhaul of that magnitude could be executed without growing pains.

With a laser focus on preventing future attacks, the TSA faced scrutiny in its early life over allegations of racial profiling. Critics accused the agency of improperly infringing on the rights of law-abiding Americans who may have appeared to resemble the perpetrators of 9/11. The agency was criticized for using travel patterns to gauge whether someone was likely to commit an attack.

"We were always trying to figure out -- who's a terrorist? How are we going to spot a likely terrorist?" Bester said.

Bester described challenges with the Sikh community, whose members were hesitant to remove their religious headwear. But she insisted that racial profiling was never an official policy of TSA, and said that the outcome -- no major attacks -- justified those challenges.

"It would be a far less safe environment for the American public if the TSA officer was not there and that whole operation was not there," Bester said. "I don't think we'll ever go back to the way it was before."

But for some communities, the targeting went too far.

"There were people who were getting stopped and interrogated at airports for wearing T-shirts that had Arabic on them," recalls Sahar Aziz, a law professor at Rutgers University. "And sometimes the language, the Arabic, when translated, was something like 'Party' or 'Hello.' But just the sign, the image of Arabic script ... it was associated with terrorism, caused people to be suspicious."

Elsewhere in government, particularly in the law enforcement and intelligence communities, the pendulum -- always suspended delicately between personal freedom and the collective national security -- swayed ever further toward security.

Alberto Gonzales, the U.S. attorney general during the Bush administration, defended the government's response to the attacks as part of a natural "ebb and flow" that was "totally appropriate" under the circumstances.

"Under extreme circumstances, liberty does have to be curtailed," Farmer said. "But they have to be extreme, and the threats have to be real."

"It's a constantly shifting balance," Farmer added, "and it's going to shift over time."

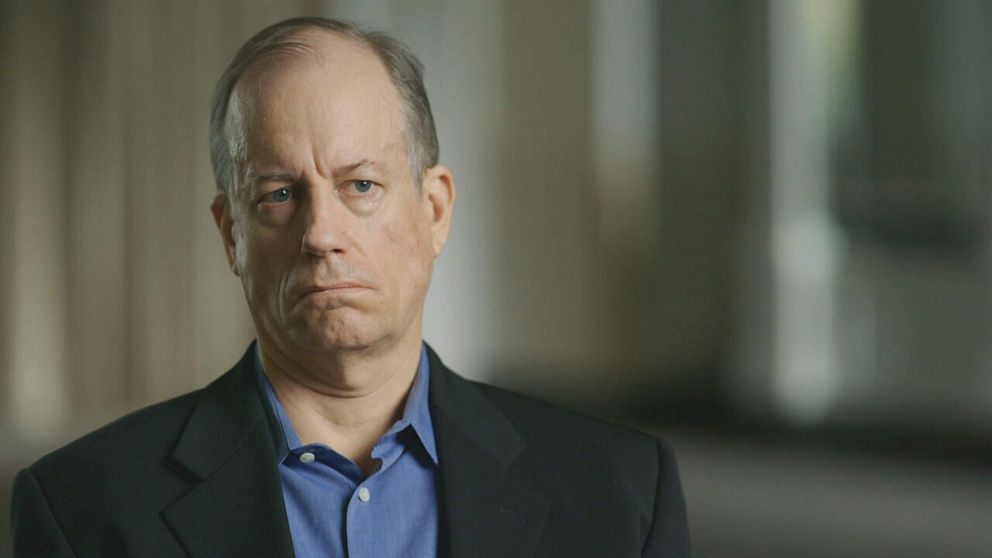

Not everyone agreed. Tom Drake, a former senior official at the National Security Agency, describes the weeks and months that followed 9/11 as an "abyss" where "the dichotomy" of security versus personal liberty "dramatically shifted to the side of security."

"Who cares about liberty? Who cares about constraints? We just need to make Americans feel safe again," Drake said, charactering the position of those who advocated for broader latitude in national security.

Drake recalled that less than a week after 9/11, Vice President Dick Cheney said on television that national security agencies would need to work on what Cheney described as the "dark side" of intelligence -- using "any means at our disposal, basically, to achieve our objective," Drake said.

To Drake, Cheney's overtures suggested that the federal government would be "more than willing to suspend, effectively, the Constitution for the sake of security," Drake said.

But Cheney has defended his statement. "Part of my job is to think about the unthinkable, to focus upon what in fact the terrorists may have in store for us," Cheney said in 2006 when asked about his "dark side" comments.

Drake says he eventually grew so disturbed by some of the activities of the intelligence community in the wake of 9/11 that he penned a memo and took his concerns to the director of NSA. He outlined several massive, expensive surveillance programs and technologies that he said were being misused -- including to monitor some Americans without an appropriate warrant.

"To say that it caused a firestorm against me would be an understatement," Drake said.

Drake became the first of several intelligence community whistleblowers to call attention to perceived government overreach in surveilling Americans in the wake of 9/11 -- a list headlined by Edward Snowden, who in 2013 leaked a cache of classified documents outlining electronic monitoring practices.

In 2007, the FBI put Drake under surveillance and raided his home. The Justice Department later charged him with espionage, but ended up dropping the case. Drake lost his career, and lost his retirement savings paying for legal fees in a protracted legal fight with the government.

"I still wake up in the middle of the night sweating," he said.

But for all that he lost, Drake stands by the virtues of his decision.

"All I did was defend a piece of paper called the Constitution, OK? That's all I did," he said. "I would not break faith or fidelity with the oath that I had solemnly sworn four times in my government career. And for that, I was turned into a criminal."

Ultimately, said Drake, "it's a false dichotomy to say that it's liberty or security. It's a false dichotomy to set them up one against the other."

ABC News' Aaron Katersky contributed to this report.