A man who spent 56 years behind bars for a juvenile conviction was just freed, highlighting old laws

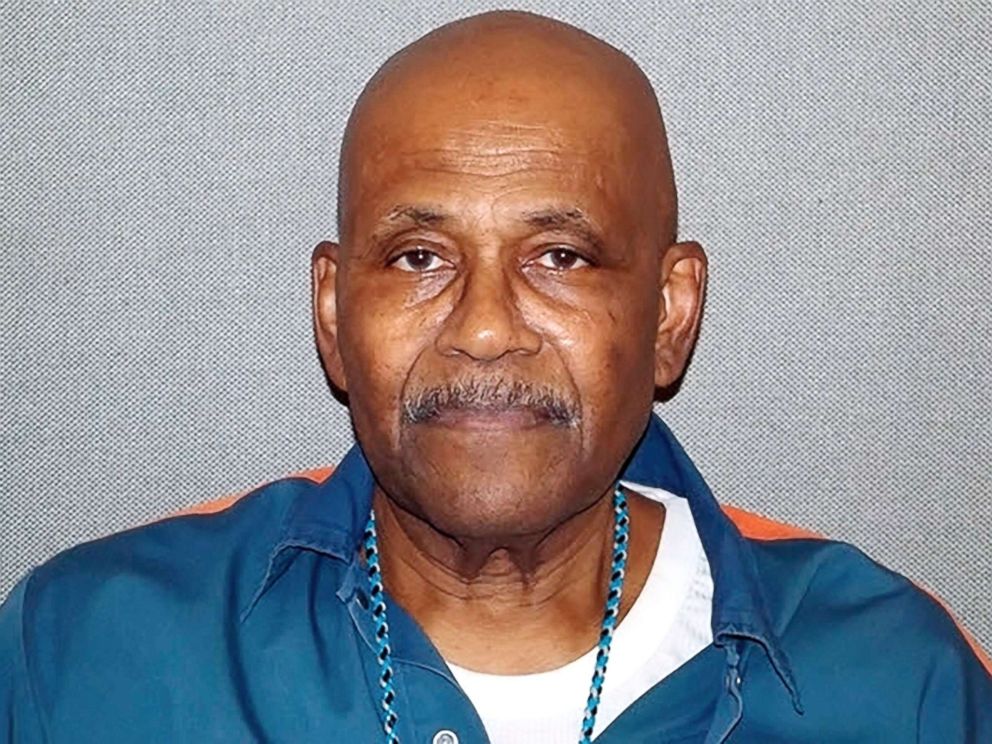

Sheldry Topp was 17 years old when he was sentenced to life in prison.

A man who went to jail when John F. Kennedy was president was finally released from prison today.

Sheldry Topp was released from a Michigan prison Thursday after serving 56 years behind bars. Topp, who is now 74 years old and is in a wheelchair, was convicted of murder when he was 17 years old.

“He had an undisputedly, an incredibly abusive home life and he was trying to run away and he decided to rob a house to get money to run away,” his attorney Deborah LaBelle told ABC News shortly before Topp was released.

At the time, juveniles, who were tried as adults, could be convicted and sentenced to life in prison without the possibility of parole.

“I don’t think anybody believed that Sheldry ever intended anything bad to happen, but things do,” Labelle said.

Topp stabbed Charles Davis in his Oakland County home in 1962.

LaBelle said that while it’s against the law for a convict to reach out to a victim’s family, she said that he has written letters for relatives of Davis if they wanted to receive them. She is not sure anyone from Davis' family has ever reached out to do so.

There have been significant changes to the criminal justice system in the past six decades: for context, the landmark case the made it required for suspects to be told of their Miranda rights didn't happen until four years after Topp was sentenced.

Another important change, especially to Topp's case, was that the United State's Supreme Court ruled in a 2012 case, Miller v. Alabama, that juveniles convicted of murder could not be sentenced to spend life behind bars without the possibility of parole.

And then in 2016, a subsequent decision ruled by the same court that the Miller decision had to be enacted retroactively.

In Michigan, each individual county court that determined the original cases for juveniles with life sentences had to resentence each prisoner in order to determine a sentence with a numeric minimum term as opposed to the previous life sentences without a number.

Mishi Faruqee, the national field director for the Youth First Initiative, a group working toward ending youth incarceration, said that the attitudes towards juvenile sentencing have changed over time.

"Young people are still developing up until their mid-twenties, particularly the parts of the brain that determine decision making and impulse control," Faruqee told ABC News. "Young people are amenable to change."

She said that while the 1970s and 1980s were marked by pushes for politicians and sentences to be "tough on crime," "the pendulum is starting to shift towards more rehabilitation and treatment rather than punishment and retribution."

"There's been a recognition within the legal community that the policies of the past are archaic and they need to be changed. And so most states now not only have a revisiting of these extreme sentences but also changing their policies around sentencing youth as adults as well as their sentences for adults," Faruqee said.

For Topp, resentencing happened this week, according to Chris Gautz, the spokesman for the Michigan Department of Corrections. A judge imposed a sentence — based off the original crime — for Topp to serve between 40 and 60 years in prison, which means that he would have became eligible for parole at the 40th year.

Topp was the oldest-serving Michigan inmate sentenced as a juvenile to life without parole.

Gautz said that Topp had accrued a number of "good time credits," which actually no longer exist in the state, but are still applicable for those who served when they were in place — they "shave down" the maximum sentence.

LaBelle said that Topp served "an exemplary sentence — he hasn’t even had a misconduct [violation while in prison] in decades."

"He was a mentor. He worked the whole time [in prison] … he took every opportunity to better himself and to work and get skills. He did everything possible," LaBelle said.

"He's much diminished. He’s now in a wheelchair. He has a brother and a sister who have been waiting for him to come home all this time. He's a kind, gentle man who has long ago been entirely remorseful for his childhood act and he would like for the first time see the night sky" as an adult, she said.

In Topp’s case, the "good time credits" meant that he was able to be released Thursday and leave prison without having to be on parole.

When the 2016 United State's Supreme Court ruling was handed down, there were approximately 370 individuals in Michigan who were sentenced as juveniles to life without parole.

Gautz said that about 150 of those have since been resentenced, either being discharged fully, released on parole or given a numeric sentence to serve.

There are still over 200 people who need to be resentenced from the county courts.

"I was surprised myself that there were still a large number that still needed to be done and it could be from a myriad of reasons," Gautz told ABC News.

According to a review of Michigan Department of Corrections data, now that Topp has left prison, there are still seven men in their 60s who still haven’t been resentenced.

All of those men have spent more than 44 years in prison.

For Topp, he will be focusing on a few "very simple things" now that he’s been released, according to LaBelle.

"He wants to go and see his brother and sister, and just have dinner with them," she said.