Through a Photographer's Lens: Martin Luther King and the Civil Rights Movement

Photographer Steve Schapiro reflects on his past work.

— -- In 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. said in a sermon: “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands at times of challenge and controversy.”

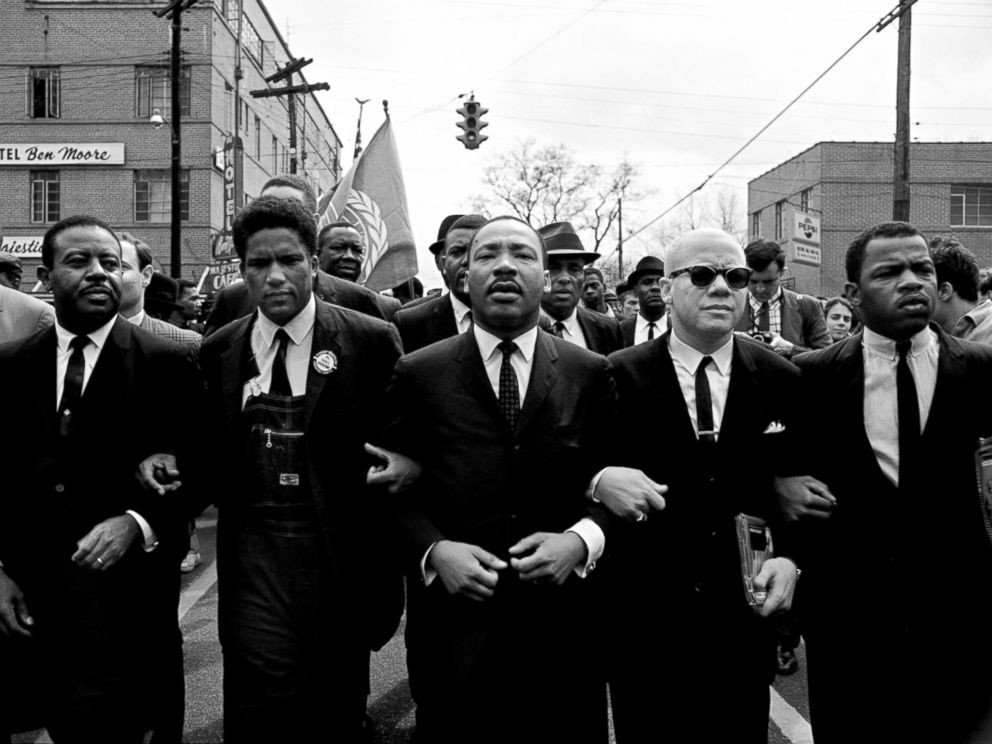

The civil rights movement came to a crossroads during the Selma-to-Montgomery march of 1965. Photographer Steve Schapiro captured the moment in an image of King linking arms with fellow civil rights activists John Lewis, the Rev. Jesse Douglas, James Forman and Ralph Abernathy. The image captures the leadership, the unity, and the strength of the civil rights leaders, who faced violence from law enforcement as well as death threats during their fight for voting rights for African Americans.

Schapiro covered two of the Selma-to-Montgomery marches for Life magazine, and while he said he knew the events were important, he had no idea the impact the images would eventually have.

“Only 300 people were allowed to participate in the third march, and there was a sense that violence might occur,” he told ABC News recently ahead of MLK Day.

King and the Southern Christian Leadership Council organized the march to bring attention to discrimination against black voters. There were three attempts to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama. This first took place on March 7, a day that would later be called “Bloody Sunday.” Alabama State Troopers charged into the crowd with batons, injuring scores of protesters.

During the second march, protesters crossed the bridge, but when they reached the end of it, the troopers were stationed there. King knelt and prayed and decided to turn back.

The third march, documented in Schapiro’s photo, took place on March 21. Although the image was not published in 1965, it has come to represent the march that marked a turning point in the movement. Following “Bloody Sunday,” President Lyndon B. Johnson called for legislation protecting the voting rights of African Americans. The Voting Rights Act was signed into law that August.

Schapiro recalled shooting 12 to 14 rolls of film that day, and would send it through baggage on American Airlines back to the Life magazine office each night, hoping that his pictures would run in the following week’s issue.

In the picture of King linking arms with other civil rights leaders, "the first thing you think of is you’ve got to walk backwards very quickly to be able to keep making these photographs,” Schapiro said. “And you’re looking for that moment when everyone has a particular look that has a sense of meaning. You’re looking for something where the design of the photo has that quality."

Schapiro said he believes that his image of the five men marching together symbolizes the positive aspects of the civil rights movement while Charles Moore’s photos of African-American protesters being sprayed with fire hoses and attacked by dogs symbolize the negative.

Growing up, Schapiro aspired to be a Life magazine photographer, so he said he gave himself assignments. Starting his career as a freelance photographer in 1961, he covered everything from an Arkansas migrant worker camp to a story on narcotics in East Harlem.

Life first hired him in 1962, and in addition to covering the Selma-to-Montgomery march and other events for the publication, he worked on a project based on James Baldwin’s 1963 book, “The Fire Next Time,” which discusses the challenges facing African Americans in the 1960s. His photographs documenting the civil rights movement along with an essay by James Baldwin will be published in March.

Though he has photographed celebrities from David Bowie to Barbara Streisand to Jackie Kennedy, he said, “My heart has always been in documentary photography."

The first time Schapiro photographed King was after the bombing of the church in Birmingham that killed four young girls in 1963.

“I always saw Martin Luther King Jr. as this incredible spiritual leader, who spoke in a way that inspired people in emotional tones,” Schapiro said. “What you don't realize is that people are human at the same time. You can be a leader and still have your own particular worries.”

King had received many death threats, and Schapiro said that Andrew Young, the executive director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was well aware of the possibility of violence at the march.

“On the last day of the Selma march, Andrew Young only let people wearing black suits in the front line because he thought someone might shoot King and they wouldn’t know which one was King,” Schapiro said. “I think King was aware of all of this. What I had not seen before was that looking at a great number of my pictures, there was something in his eyes. I don’t know what the right word is -- forbearance, perhaps. Looking at the crowd and searching for who is there, not to smile at them or wave at them, but with a degree of concern and knowing that the prospects of danger were there at all times. And he had experienced this for years.”

Some of King’s stoicism and vigilance comes across in another iconic image that Schapiro took.

In the image, which was also taken at the Selma-to-Montgomery march, King gazes at the camera with a flag behind him. As Schapiro was taking it, he said he knew that the photo had a symbolic structure and that it captured the spirit of the civil rights leader.

However, the fact that 50 years later, Schapiro would see his image on the t-shirts of participants in the 50th anniversary Selma-to-Montgomery march still amazes him, he said.

“You would constantly be moving and seeing so many things that you never could pin down something as being historical or anything like that,” he said. “You took a lot of pictures and you really were trying to get a sense of the people, a sense of the event, a sense of the subject and if you did that, you felt successful.”

ABC News' Emilie Richardson contributed to this report.