Rape kit backlog initiative in Missouri sends 1st batch to labs

The state AG's office plans to test 1,250 kits over coming months.

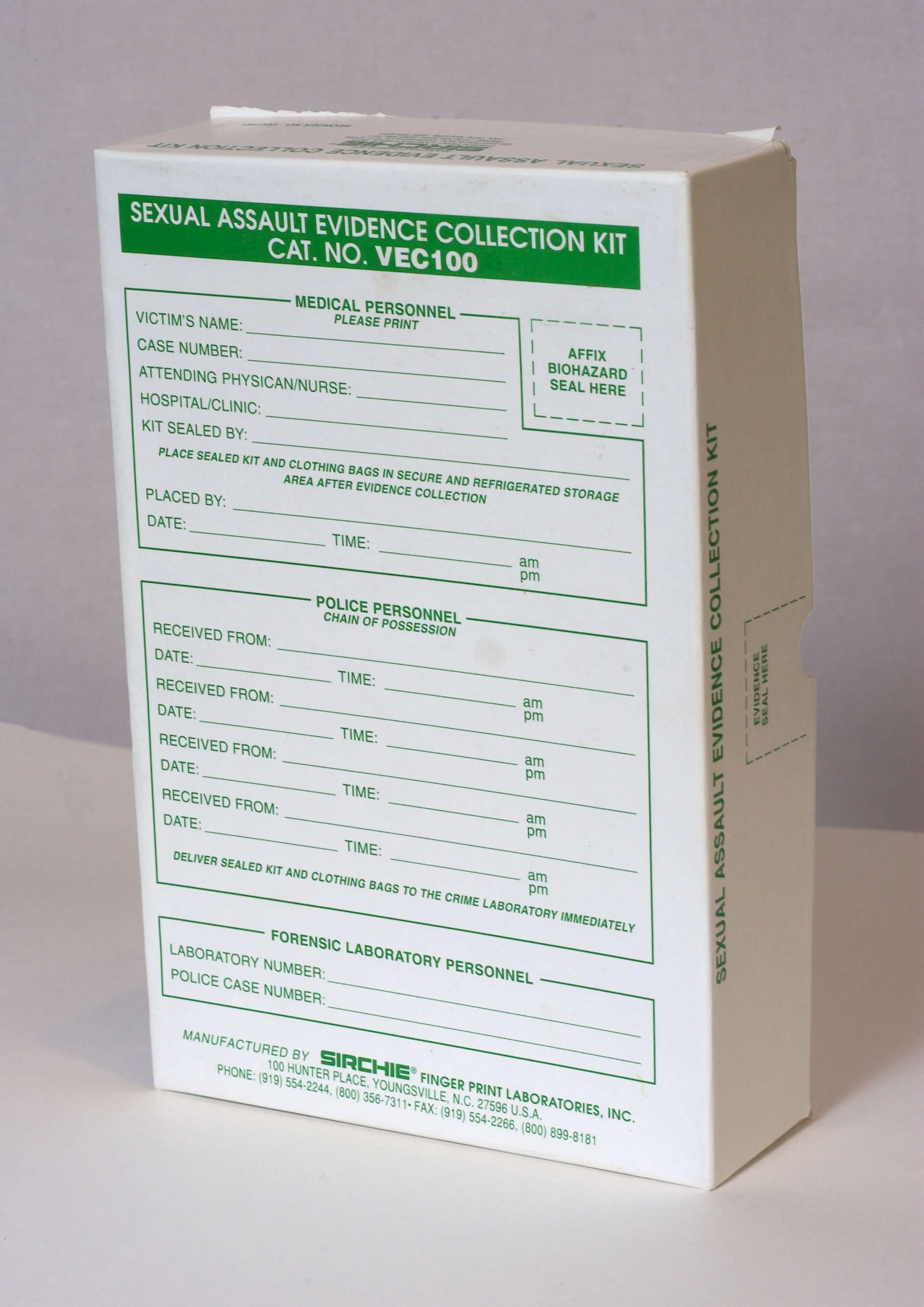

A batch of rape kits that have been sitting on a shelf in Missouri has been sent to a lab for testing as part of the state's new initiative to clear out its backlog.

"We will move as quickly as we can to get as many kits tested," Missouri Attorney General Eric Schmitt told ABC News.

Missouri has thousands of rape kits that have not been tested, according to the AG's office, and advocacy groups say they hope this initial effort will help strengthen the efforts -- and, importantly, funding -- to get the remaining kits tested.

The attorney general said his office aims to get 1,250 kits tested over the next few months using a $2.8 million grant from the Department of Justice, which will also help in the prosecution of rape cases throughout the state.

The first batch included over 100 kits that will be tested by a third-party lab, Schmitt announced on Jan. 23. Their results should be ready within 60 to 90 days.

On average, it costs between $1,000 and $1,500 to test one kit, according to the Joyful Heart Foundation, a nonprofit that runs the End the Backlog campaign.

Some police offices, particularly the smaller ones, lack the resources and protocols to properly test the kits and hold on to them while waiting for a lab window to open up, according to the nonprofit, leading to backlogs.

These kits represent someone who has been through a terrible ordeal.

Other states are working to catalog and decrease their immense backlog including North Carolina, which has over 15,000, and Texas, which has over 2,000, according to the Joyful Heart Foundation. Ilse Knecht, Joyful Heart's policy and advocacy director, said the backlog has stalled thousands of rape investigations and prosecutions around the country and left victims who took a rape kit test frustrated and afraid that they'd never get justice.

"These kits represent someone who has been through a terrible ordeal," Knecht told ABC News. "They've done everything society has expected them to do. So when they sit on shelves and don't get tested, we're sending them a terrible message."

This lab testing is the start of the final phase of a three-part plan put in place by the Missouri AG's office last year to clear the state's backlog. Last year, the office kicked off the initiative by teaming up with victims groups, hospitals and police precincts from across the state to count and locate every kit that hadn't been processed. They found 6,800 kits were in storage.

In November, phase two began when Schmitt's office put out a report detailing the backlog by county and created a chain of command protocol for the transfer of kits from smaller hospitals and precincts to "host agencies," such as the larger Springfield Police Department.

Those agencies will hold onto the kits send them to the third-party lab that was selected by the state. The kits are also tracked by a database, according to Schmitt.

"We made sure this was a very collaborative effort," he said.

Knecht said Missouri's system is comprehensive and noted the tracking system and third-party lab were key components in getting the kits tested properly and efficiently. She added the tracking system would be able to flag if a kit has been idling in the process for too long.

"When I see a state outsourcing the kit, I see it as a sign that they want to get this done quickly," she said. "It can be the most efficient way to get rid of the backlog."

Knecht added that there is still more work to be done. She recommended the state consider opening up the backlog database and tracking system to victims so they can see the status of their kits in real-time.

Most importantly, Knecht said the state should get more funding to pay for the additional backlogs. Last month, President Donald Trump signed a law that would provide federal funding to test 100,000 kits around the country.

Schmitt said he will make requests to the federal government for more funding to get to the remaining 5,550 kits into the system and tested.

"We want to help them," the attorney general said of the victims. "We will do everything we can. There are dollars out there."