The Reasons 'Serial' Subject Adnan Syed May Receive a New Trial

“We already knew the cell evidence was weak, this just confirmed it.”

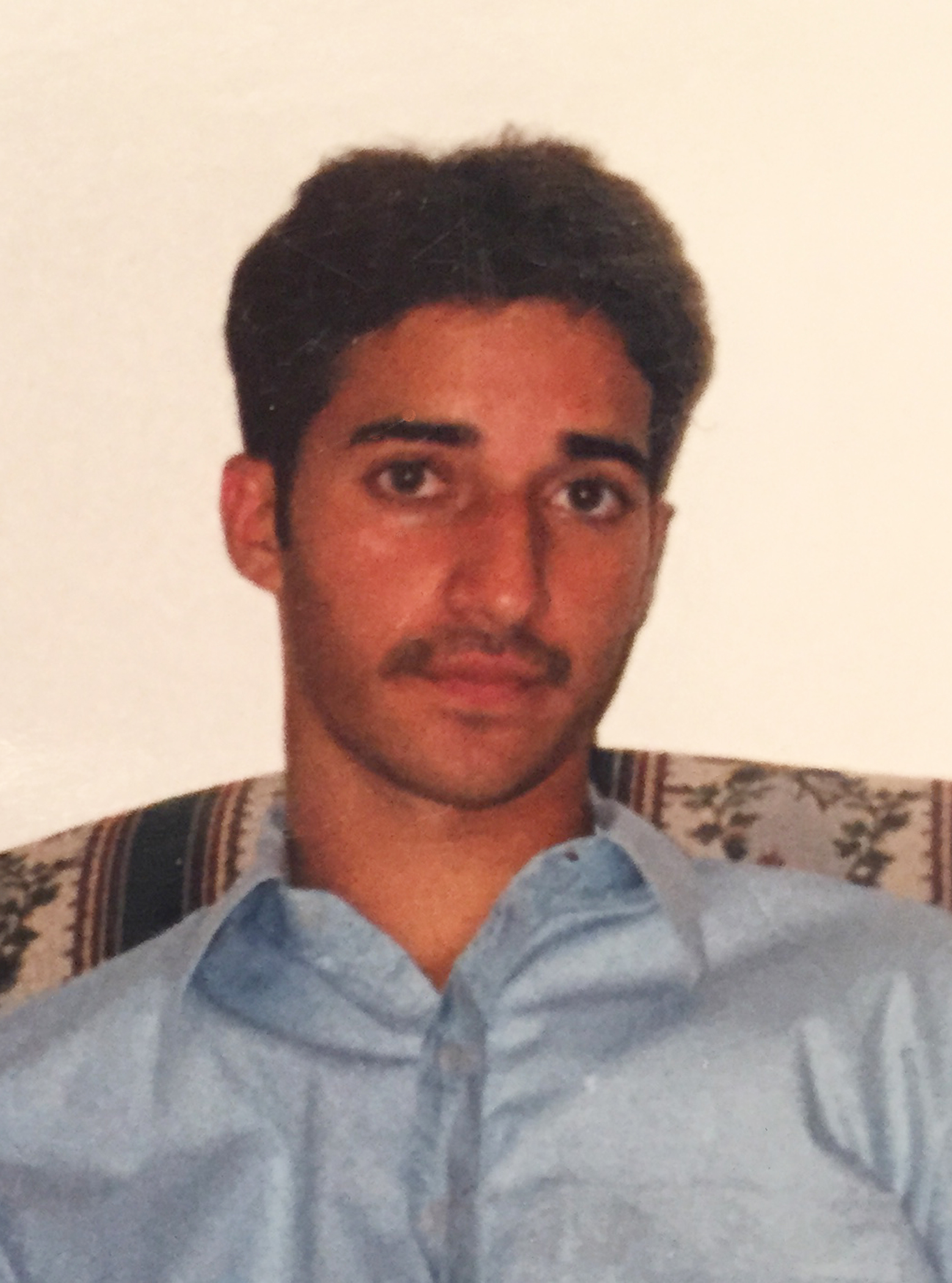

— -- One week ago, 2014 “Serial” podcast case study Adnan Syed received the best news he’s likely heard in 17 years: his murder conviction was vacated, he is now presumed innocent and a new trial has been granted.

In a 59-page ruling delivered by a retired Baltimore Circuit Court judge, the judge issued a firm rebuke of the process that landed the young American-Pakistani boy behind bars for the rest of his life.

Syed was only 17 years old when he was arrested for the murder of Woodlawn High School student Hae Min Lee in 1999. Police immediately honed in on Syed because he was Lee’s ex-boyfriend. He was charged, tried as an adult, and convicted during a trial in 2000. He received a life sentence plus 30 years – without physical evidence that tied him to the crime.

Instead, the prosecution used the testimony of an alleged accomplice that claimed he helped Syed bury Lee’s body, and cell tower location data, still developing technology at the time, in their argument against Syed. A jury convicted him in less than two hours.

This new ruling by Judge Martin Welch comes following the added attention Syed’s case received as a result of being featured on the ‘Serial’ podcast, which grew into a large national audience invested in learning about his fate. Subsequently, the many questions that remained unanswered during his case have come to light -- including whether his lawyer at the time represented him properly and whether the non-physical evidence presented by the prosecution was reliable.

Welch said he based his new June 30th ruling on those questions. He cited a series of blunders made by Syed’s trial attorney, deeming her “ineffective” for failing to vet and question a key cell phone expert that helped prosecutors pin Syed near the location of a makeshift, 6-inch grave where Lee’s strangled body was found. He also concluded the state presented a “relatively weak theory” for the events leading up to Lee’s murder, saying prosecutors relied upon “inconsistent facts” to support its timeline.

He added that he was “perplexed” by the testimony of an experienced FBI Special Agent the state called as its cell tower expert during Syed’s second post-conviction relief hearing earlier this year. Welch also considered it an error that Syed’s lawyer failed to contact potential alibi witness Asia Chapman McClain, saying her “performance fell below the standard of reasonable professional judgment.”

Chapman was finally called to court during a five-day hearing in February this year, where she stood by her account of the day she sat and chatted with Syed in a public library about relationships and life, the same day and time the state maintained that Syed murdered his ex-girlfriend, Lee.

The new ruling stunned the audience that has been following Syed’s case and spurred a media storm of coverage over the past several days, presenting the wildly popular “Serial” as Syed's torch of justice, along with the handful of lawyers and advocates who intensely investigated his case behind the scenes.

“I love ‘Serial,’ it’s a great podcast, but it’s pretty skimpy on legal details.”

Another story that is less-often discussed is the hawk eye and fascination of one “Serial” podcast listener who uncovered the smoking gun that helped Syed’s lawyers successfully argue for a new trial.

Susan Simpson is a trained attorney who took up keen interest in Syed’s case because of “Serial,” blogging and posting on Reddit “just for fun” after each episode, sharing her thoughts about the case.

A full-time employee of the Volkov Law Group based in Washington, D.C., Simpson's primary focus is on white collar crime, so she said the side project kept her busy.

“[Serial] was not written for lawyers, not made for lawyers, which is not a criticism. But, as an attorney, I wanted to fill out the legal details for myself,” Simpson told ABC News. “So, I started going through the available resources and trying to piece together the picture.”

It wasn’t long before her blog caught the attention of Rabia Chaudry, a Syed family friend, lawyer, and author of the soon-to-be published book “Adnan’s Story: The Search for Truth and Justice After Serial.” Chaudry first brought the case to “Serial” producers and was featured on the podcast.

Chaudry offered Syed’s entire case file to Simpson to see if she could dig up anything on her own. Simpson said she initially hesitated, admitting she didn’t think it was a great idea, but ultimately agreed to take a look at the unorganized and massive collection of files.

She began organizing the files to better understand them, eventually coming across a Maryland public records request, which included fax headers concerning how to read AT&T cell phone records.

“I’m like great, the records I’m looking at are subscriber activity reports, lets figure out how to read this,” Simpson said.

“The first line is like, it’s bold and it’s caps and it says ‘incoming calls are not reliable for location status’ and I think I read it like three times, and then I made my husband read it cause he’d gotten home, and I was like ‘tell me that I’m actually reading this and I’m not just making it up in my head cause this is way too simple to actually be what I’m reading',” Simpson recalled.

Chaudry described her initial reaction when Simpson came across the disclaimer.

“I was a bit shocked because it was something so obvious and elementary and I immediately realized this was a big, big deal in undermining the state's case,” Chaudry said to ABC News. “We already knew the cell evidence was weak, this just confirmed it.”

Exhibit 31

In 2000, the state’s cell tower expert testified that two incoming calls received on Syed’s phone at 7:09 p.m. and 7:16 p.m. on January 13, 1999 pinged a cell site that provided cellular network coverage to an area encompassing the burial site where Lee’s body was found in Leakin Park, a large public park in Baltimore, Maryland. The state urged the jury to make a reasonable inference that Syed’s cell phone was possibly located in Leakin Park during the time of the burial, which Syed’s alleged accomplice testified as being at approximately 7:00 p.m. on January 13, 1999.

At the time of Syed’s trial, both his lawyer and prosecutors possessed an AT&T fax coversheet that was obtained during pretrial disclosure. The fax cover sheet contained a set of instructions labeled, “How to read ‘Subscriber Activity’ Report.”

These specific set of instructions also included a disclaimer, specifying that “Outgoing calls only are reliable for location status. Any incoming calls will NOT be reliable information for location.”

Syed’s lawyer never brought the disclaimer up during his trial, which could have helped undermine the state’s reliance on the two incoming calls that placed Syed’s cell phone at the location of the burial site, and during the time of the burial.

“It did become clear that this [disclaimer] wasn’t an accident,” Simpson said. “Someone didn’t randomly write this down one day and say ‘You know what? This is going to be fun. Let’s just write some random instructions here that don’t mean anything and then pass them out to law enforcement’.”

In April 2015, Simpson, Chaudry, and Colin Miller, a law professor at the University of South Carolina School of Law who Simpson met online in a Reddit comments section discussing the case, teamed up to launch the “Undisclosed” podcast, an unaffiliated spin-off of “Serial,” picking up where “Serial” producer and narrator Sarah Koening left off. Their podcast further analyzes the police investigation into Lee’s murder, taking listeners on a deeper dive into the circuitous legal system that Syed, now 35, has endured.

The three discussed the newly found and rediscovered disclaimer on the podcast, before it finally made its way to Syed’s current lead defense attorney, C. Justin Brown.

“He did listen to the podcast and hear about the cell phone records and realized that they were critical,” Simpson said.

The disclaimer was argued about in court at Syed’s February hearing.

Welch, in his ruling last week, found that Syed’s trial lawyer did indeed render “deficient performance when she failed to properly cross-examine” the state’s cell expert about the disclaimer, which in turn “allowed the jury to deliberate with the misleading impression that the State used reliable information to approximate the general location of [Syed’s] cell phone during the time of the burial.”

For Simpson, Chaudry, and Miller, the ruling was a complete shock, surprise, and a clear validation.

Armchair Detectives

“If anything, it can be a wake-up call for courts all over the U.S. to be a little more careful with how they’re judging scientific data and try to put more of the science back in forensic science,” Simpson said. “It perfectly illustrated in Adnan’s case the dangers of misuse of forensic science and that’s ultimately what this comes down to, is lawyers, prosecutors and defense attorneys looking at scientific or engineering evidence and saying ‘I know how to use this to fit my case. I don’t know how it works, I don’t know what it means, but I can twist this around to work for the case’,” Simpson said.

Simpson, Chaudry, and Miller all agree that the intersection of social media and journalism and investigation all played a huge part in not only bringing attention to Syed’s case, but also bringing the three of them together.

“We’ve gotten a ton of great info from people on social media. They’ve offered up theories, they’ve offered up friends who are expert witnesses and other information that we haven’t disclosed yet,” Miller said. “To be able to have thousands or even millions of eyes to be looking at these documents, everyone brings their own experience and skill set to these documents. Look at Susan Simpson,” Miller said in an interview with ABC News.

But armchair detectives they are not.

“Certainly you can have danger of people without experience drawing the wrong conclusions, and having a bit of a witch hunt, and having people wrongfully accused,” Miller said. “I think the advantage Rabia, Susan and myself can bring to the table is we're all lawyers, and we have the training and education and experience to be able to look at it through a different lens than someone without the acumen might bring to the table."

Their next step is to continue investigating Syed’s case – which they hope leads up to a potential new trial sometime next year – but they’re also working on a second season of “Undisclosed” that will begin streaming July 11. And they’ve added a reinforcement: Emmy-Award winner Jon Cryer of Two and Half Men fame will be joining them as a host.

“Our eyes will always be on Adnan's case. We know there is much further to go and the three of us aren't just interested in getting him out of prison, but we want to actually solve Hae's murder and are actively pursuing leads on that,” Chaudry said. “We've been investigating a new wrongful conviction that was brought to us by a state Innocence Project, and working full time jobs.”

Syed’s Next Chapter

Now that Syed finally has a shot at a new trial, he’s not taking any chances. His attorney announced Wednesday that a pro-bono team of lawyers with experience in wrongful convictions from the global law firm Hogan Lovells will be joining him as co-counsel in representing Syed.

“The firm’s substantial litigation experience in Baltimore, coupled with its successful track record in innocence cases, makes them the ideal firm to help get Adnan out of prison,” Brown said in a statement.

But the Maryland Office of the Attorney General has promised to appeal Welch’s decision, announcing in a statement released last week, “The State’s responsibility remains to pursue justice, and to defend what it believes is a valid conviction.”

Lee’s family issued their own statement, expressing their disappointment in Welch’s decision, standing behind their belief that Syed is Lee’s true killer.

“We continue to believe justice was done when Mr. Syed was convicted of killing Hae.”

Simpson said they’re still looking into several different suspects who may have killed Lee. But the focus will be on giving Syed his best chance in court by having a solid defense.

“You have to have an attorney that follows every reasonable lead because you never know which is going to end up mattering,” Simpson said. “I’ve helped him find one that matters this time around but it’s very much being able to cover as much investigation as you can, and to learn as much as you can about everything because again, it could be something as simple as one piece of paper that ends up making the day.”