Documentary traces history of policing the Black community – from slavery through present day

"Sound of the Police" begins streaming Aug. 11 on Hulu.

Days after the fatal police shooting of Amir Locke last February, community activists gathered at the Minneapolis City Hall in protest.

"We're here for Amir Locke. The question that I have is: How many more?" said Rod Adams, a community organizer who spoke at the event. "Seven years from Jamar Clark, we're 18 months from George Floyd, and now we stand here, dealing with another murder of a young Black man."

Locke, 22, was shot and killed by Minneapolis police officers as they executed a "no-knock" warrant – the controversial practice that allows officers to enter a private home without knocking or making their presence known.

Locke was not a suspect in the crime for which the warrant was issued and was not named in the document. A licensed gun owner, he had been sleeping under a blanket on the couch when police entered the home. Body camera footage shows a gun in his hand when he begins to sit up as police approach him. An officer can be seen shooting Locke less than 10 seconds after entering the room.

In "Sound of the Police," a new Hulu original documentary produced by Firelight Films for ABC News Studios, Locke's death is framed as just one example that illustrates the fraught relationship between police and the African American community. The film traces the country's complex racial history that set the path for policing in Black communities – from the formation of slave patrols in the early 1700s, to the advent of Jim Crow, to the uprisings against police brutality in the latter half of the 20th century and recent acts of police violence against African Americans that has garnered widespread media attention.

No charges were filed against the officers involved in the Locke shooting. Public condemnation of the incident led the city of Minneapolis to institute a total ban on no-knock warrants.

Adams, executive director of New Justice Project MN, says he lived right across the street from the building where Locke was killed. When he learned of the police shooting that day, he went outside to see what was going on.

"After I was out there about an hour or two, they brought his body out. Later in the day, I saw the bodycam footage. And the image that just stuck with me was them being very, very quiet, as silent as possible, putting that key in the door, opening it, and, like, literally snuffing this man out as he slept," Adams said.

"Sound of the Police" also looks at contemporary efforts to confront and resolve the conflicts.

"It seems to be two forms of policing in America – one for white America and another for Black America," Benjamin Crump, a civil rights attorney, says in the documentary.

This chasm has deep roots going all the way back to slavery, according to experts and civil rights activists interviewed in the film. Slave patrols emerged in about 1704 in the Carolinas, where they "were used very specifically to patrol racial boundaries," between free whites and any person with visible African ancestry, historian Terry Anne Scott says in the film.

"The slave patrols were deputized to go and recover white men's property, which were Black people. Under the slave laws, slaves are automatically guilty, and any Black was automatically slave status," civil rights activist the Rev. Al Sharpton says.

The abolishment of slavery in the Northern colonies created an incentive for enslaved Black people to escape the South. Ads featuring runaways bought by southern enslavers were the most common form of newspaper revenue in the nation, according to historian Khalil Gibran Muhammad.

The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 empowered any white person to capture a Black person and return them to their enslaver, setting the stage for a "regime of surveillance and universal suspicion for Black people, even free people, even people who were born free," historian and Columbia Journalism School dean Jelani Cobb says in the film.

"There was no qualitative difference between law enforcement in the so-called free states and in slave catchers coming from the South. It was a hand-in-glove operation, all at the expense of Black freedom. The impact of 1850 was, it removed any hope that there was somewhere we could hide," Sharpton says.

Centuries later, historians draw parallels to recent incidents of weaponizing the police against Black people, such as a viral 2020 incident in which a white dog owner called 911 on a Black birdwatcher who had told her to keep her pet leashed in New York City's Central Park.

"When a white person threatens to call the police on a Black person during a tense situation, that person is marshaling this long history of racist enforcement and the double standard of justice in America," historian Elizabeth Hinton says in the film.

The documentary goes on to trace the troubled, and often racist, history of policing the Black community into the post-Civil War era and beyond.

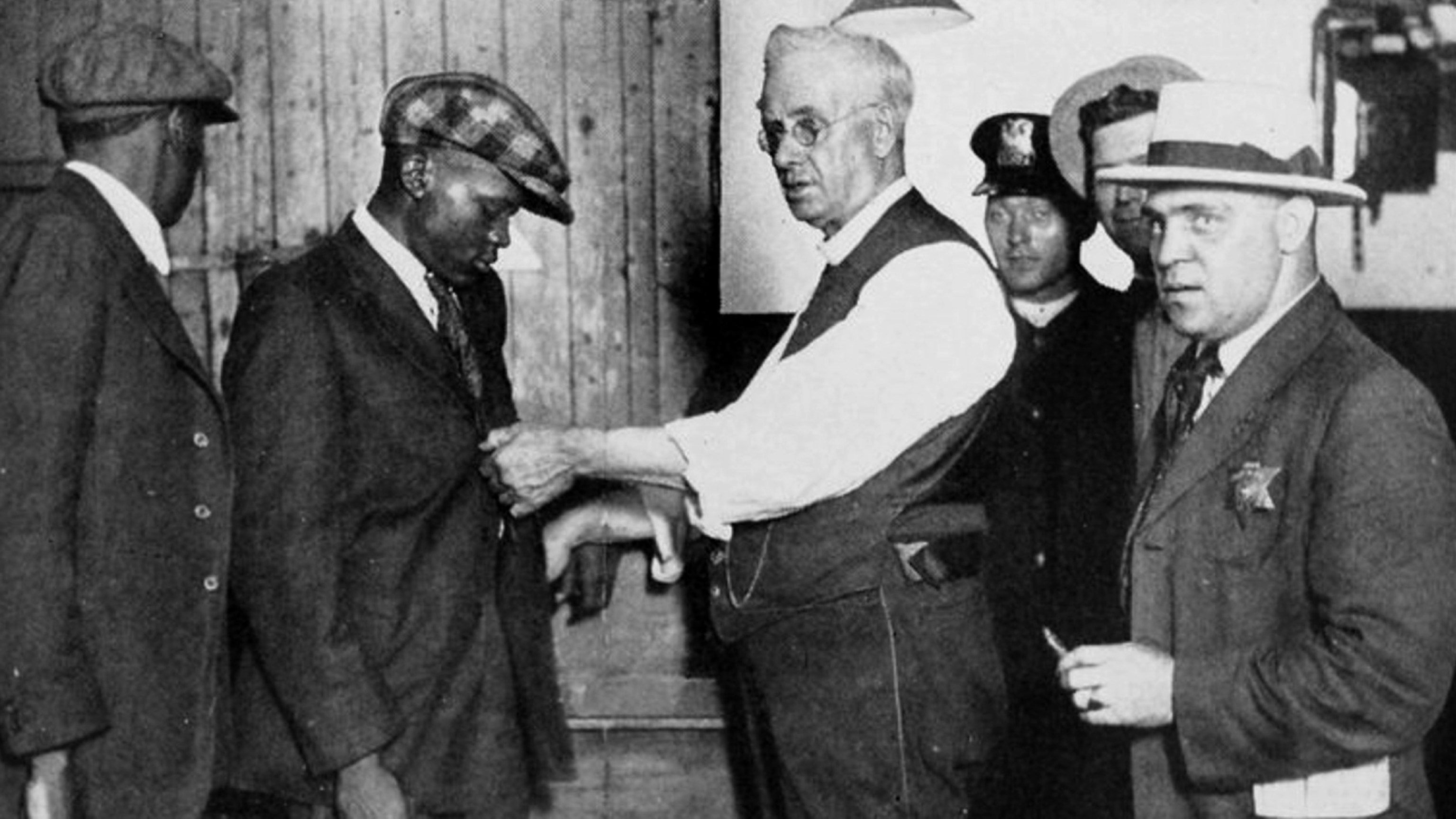

Incidents of mob violence carried out by white citizens were, in many instances, condoned or helped by law enforcement themselves, according to historians interviewed in the film. After the Great Migration, segregated Black communities saw heavier policing in the forms of practices like "stop and frisk" – the right of law enforcement to stop, question and pat down anyone deemed reasonably suspicious.

"Black people were experiencing a sense of living in an occupied territory. Police were an occupying force as if you were a conquered people and the conquering army set up checkpoints and military posts in your community. And that any show of resistance to this experience of oppression could result in detention, arrest, or death. This created some of the groundswell of tension that would eventually lead to acts of racial violence," Muhammad says.

When Los Angeles police officers were seen on video brutally beating Black motorist Rodney King in 1991, images circulated in the mainstream public discourse that "much of Black America knew about" and had seen firsthand in their own communities, Cobb says.

The proliferation of smartphones put cameras into everyone's pockets and has only increased that visibility. For example, bystanders have been credited with documenting on their phones numerous incidents of police brutality, such as the murder of George Floyd in May 2020.

"Before that happened with a camera, people could debate, 'That's impossible. This is America. Y'all are making this up.' When you got the video, it changed the conversation," Sharpton says.

Still, progress has been an uphill battle, with many police departments resistant to change, civil rights activists say.

For people like Karen Wells, Amir Locke's mother, it's a painful reminder of all that's been lost.

"I think about Amir every day, all day. Amir should be here," says Wells. "There is no reason why my son should be in an urn right now, that I have to look at every day as a reminder. I feel like because of the color of his skin, he didn't have a chance. No mother should have to bury their child. He's not coming back. He's gone."

"Sound of the Police" begins streaming Aug. 11 on Hulu.