Touring Mexico's Most Violent City

Tourism and Drug Violence Live Side by Side in Mexico's Most Murderous City

March 5, 2013— -- You might feel quite pleased about life if you go to Acapulco, Mexico. The snazzy high-rise hotels provide beautiful views of the deep blue sea. The weather is deliciously warm. The city itself sits on a picture perfect bay, framed by small hills and white houses that give the area a Mediterranean feel.

But as you stroll along these beaches, your tranquility can be somewhat interrupted by the thought that you are actually in the world's second most violent city. In fact, Acapulco's murder rate of 142 killings per 100,000 residents is 28 times higher than the U.S. average.

These crimes happen mostly in working class neighborhoods that are just a short drive away from the luxury apartments, the cute vacation homes and the international franchise stores that line Acapulco's coastal strip.

On the last Wednesday of February for example, the daily death toll included a man who was burned alive in his car, two women shot to death by someone who broke into their home and another man killed with an AR-15 assault rifle, a military-grade weapon. And this is in a country with just one legal gun store.

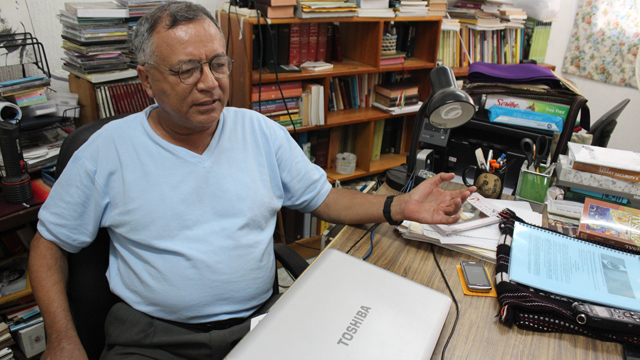

"That's the sad reality of our Acapulco," said local crime reporter Martin Basurto, who spends much of the day lingering outside the headquarters of SEMEFO, the local forensic service.

Basurto follows investigators when news of a crime breaks, so that he can take pictures of the city's dark underbelly for local newspaper, El Sol del Chilpancingo.

He says that violence in the city started to skyrocket in 2009, after the drug lord Arturo Beltran Leyva was killed in Cuernavaca by Mexican security forces, sparking a struggle for control of Acapulco's profitable drug market among rival gangs.

The result: Basurto has seen dozens of beheaded bodies, victims with their limbs chopped off and some mass execution sites. There have also been a few "desollados" to take photos of Basurto said. He explained that desollado is the Spanish term for a victim whose skin has been peeled off his face.

But even after seeing all this gruesomeness, Basurto insists that his city is ok for the tourist crowd.

"You can't say that tourists are being targeted here," Basurto said, explaining that the city's tourist strip had only one murder in the past three months. He added that the crime problem "is in the periphery," meaning the neighborhoods away from the coastal strip. In those areas there have already been 200 murders in the first two months of this year.

Officials in this iconic Mexican tourism spot do not publish stats on what areas of the city have been most affected by the high murder rates. There is also no public information on which areas of Acapulco are most heavily patrolled by police.

But you can start to discern the stark contrasts in security by just walking -- or driving -- through the city's different neighborhoods. The Avenida Costera, where most hotels are located, is regularly patrolled by Mexican Federal Police Officers who zoom by tourists in shiny blue and white pickup trucks with long-range semi-automatic weapons.

When hotels and conference centers organize special events, local officials double or triple the number of police in those areas and set up checkpoints where cars are searched. In neighborhoods that are a couple miles away from the beach, patrols are less frequent.

Father Jesus Mendoza said that, in his parish of La Laja, criminal gangs that five or six years ago focused solely on selling drugs have diversified into kidnappings and "taxing" local businesses as they seek new sources of steady revenue.

"Vendors with fruit and vegetable stalls at the market were recently being charged some 20 pesos [$2] per day," said Mendoza, who hears constantly about local crime problems from parish members. According to him, some local school kids were also kidnapped in this area last year by criminals who asked for "liberation" fees of $30,000 to 50,000 pesos ($2,000-$4,000).

"Fifteen years ago, they only used to kidnap people with a lot of money," said Mendoza, who has worked in La Laja for almost two decades. "Now anyone can be a kidnapping victim."

Compared to the tourist zone, he said his area gets "second rate" treatment.

"For the Christmas holidays, the government sent 500 extra soldiers to Acapulco, but most of them were in the tourist area," Mendoza said. He added that his neighborhood is patrolled mostly by municipal police, who have less training and are more likely to be "infiltrated" by local gangs than the federal and state police officers who cover Acapulco's tourist strip.

Mendoza's suspicions about corruption in the municipal police are probably correct. Acapulco is currently planning to lay off 500 police officers who have not passed anti-corruption background checks. The number of cops whose job are going to be cut is equivalent to 40 percent of the city's police force.

So is security in Acapulco a privilege of the rich?

"It's not [a privilege] of the rich, but of the tourist zone," Acapulco mayor Luis Walton told ABC/Univision. Walton acknowledged that security in the working class neighborhoods of Acapulco was "not the same" as in the tourist zone. But he said that federal forces should continue to focus on protecting Acapulco's hotel strip.

"If we do not protect tourists, the city will lose its income. Tourism is the only big industry in this city," said the mayor, who faced a barrage of media criticism after six Spanish tourists were raped in February in one of Acapulco's rare incidents of scandalous crimes against foreigners.

According to Walton, the municipal government is working on solutions for crime in the city's poor neighborhoods. Such solutions include better coordination with state and federal law enforcement forces, and investment in social programs, like sports clinics, meant to prevent kids from joining gangs.

Walton has also asked for an extra 800 million pesos from the Federal government to expand the water supply to include areas of the city that currently get no running water.

But some residents of Acapulco want more immediate solutions to the problems affecting their communities.

On February 24, federal police forces were busy increasing security arrangements around a five-star hotel which was set to host the annual Mexico Open Tennis Tournament. Meanwhile, residents of Acapulco's rural area announced they would form self-defense squads that will patrol certain parts of the municipality with their own antiquated guns.

"In this [rural] region of Acapulco, kidnappings have been intensifying, as well as robberies of cattle, pick up trucks and murders," said Carlos Garcia, one of the organizers of the self-defense squad, also known as a "community police force." Garcia said that twenty rural and suburban communities have already decided to join his makeshift organization, which will be run by a community development group called Union Popular.

"We're already working on sustainable development in the region, with issues like ecological agriculture and food security. Now we need to ensure the security of people," said Joel Mendoza of Union Popular. The self-defense group plans to train ten volunteer "policemen" in each community that joins their group.

One area that will not yet join such programs is the Costera hotel zone, where murders are low and criminal gangs do not yet seem to be taxing local businesses on a large scale. But the violence present in other areas of the city is already having an adverse effect on this part of town.

Laura Caballero directs the Association of Costera Retail Businesses, an organization that represents 200 souvenir shops, clothing stores and restaurants located on Acapulco´s tourist strip. She says that over the past two years, half of her association's affiliates have gone out of business because Acapulco's bad reputation drives tourists away.

"People simply don't come here anymore, even if nothing [crime related] happens in the tourist zone," Caballero said. "Our businesses used to open until 1 a.m. or 2 a.m., but now nobody wants to walk the streets after 11 p.m."

Hotels have also suffered in this city, which depends on tourism for at least 75 percent of its income. According to the Secretariat to Promote Tourism in the State of Guerrero --where Acapulco is located-- occupancy rates for Acapulco hotels dropped from an average of 56 percent in the first 9 months of 2006 to 44 percent for the same period in 2011.

But Javier Aluni, the Secretary for Tourism Promotion in Guerrero, told ABC Univision that hotel occupancies for the first two months of 2013, were the strongest since 2009 thanks to a large influx of tourists from Mexico City, which is just a five hour drive away.

"The crime that happens in Acapulco does not (generally) happen in the tourist zone, but in parts that are far away" Aluni said, suggesting that some people tend to "generalize" too much about the city, and paint all of its neighborhoods with the same brush.

But locals say that Acapulco's once booming tourism industry has also declined due to several other factors aside from violence, such as aging infrastructure, lack of promotional support from the federal government and competition from newer destinations like Los Cabos.

But violence remains king when it comes to scaring tourists away, and even worries some seasoned visitors.

"I'm hosting five Germans here, but I'm not talking to them about the crime situation," said Martha Padilla, an affluent housewife from Mexico City, who doesn't want her visitors to get stressed out over staying in the vacation home she owns in Acapulco.

Waiting in line outside one of the courts at the Mexico Tennis Open -- an event she has attended for the past 12 years in the resort city -- Padilla said that reports of violence in Acapulco have not kept her away. But she also said that she is "adapting" to the current situation by staying in her apartment at night, and no longer going for evening runs on the city´s beach.

"As long as you can move around in your country, you feel at home" Padilla said. "But I don´t feel so at home in Mexico anymore. I don't feel like I can just go anywhere around here."