Looking Back on 50 Years of Latin American Literary Rock Stars

Celebrating 50 years of the Latin American Literary Boom.

Nov. 14, 2012— -- The explosion may have happened long ago, but its echoes are still being heard. Almost half a century separates the publication of The Time of the Hero by Mario Vargas Llosa in 1963 and the concession of the Nobel Prize in Literature to the Peruvian novelist two years ago, two benchmarks that could serve as bookends to the remarkable literary movement known as the Latin American Boom, an unprecedented burst of creativity, genre-bending works and success that came out of the sub-continent in the 60's and 70's.

Even though the critics still quarrel about the first sign of the explosion, the cultural foundation Casa América chose Vargas Llosa's novel (originally published in Spanish as La Ciudad y Los Perros), as its beginning, and this week is celebrating its 50 years with a congress in Madrid. It is a perfect moment, then to re-discover those writers and works that forever changed the face of Latin American literature.

New Faces, New Perspectives

There's not one single element that defines the Boom (not even age: 22 years separated Vargas Llosa from Boom-fellow Julio Cortázar) other than being published in the same lapse of time — most of the masterpieces associated with the Boom were produced between 1962 and 1970. But stylistic similarities do exist: most of the novels share modernist traits (nonlinear use of time, shifting perspectives) while breaking apart from traditional ideas of what was allowed in fiction. This freewheeling spirit took them in different directions — from Vargas Llosa's raw depiction of reality and use of profanity to García Márquez's naïve-yet-powerful magical realism to Cortázar's read-it-as-you-wish novel Hopscotch.

In a more significant way, the members of the Boom made Latin American literature a cosmopolitan affair, and in turn became international superstars themselves — our own literary rock stars. In this sense, it is not a small coincidence that the arc of the Boom parallels that of The Beatles. The Time of the Hero was published the same year that the Fab Four began to change the face of pop music with their Liverpool take on rock and roll, and the movement's most celebrated work, One Hundred Years of Solitude came out just four days after the Beatles' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band. And just as García Márquez combined his newfound narrative techniques with the memories of his childhood in Aracataca, Colombia, Lennon and McCartney mixed sights, sounds and memories of their childhood with cut-and-paste techniques to create the most enduring album of the psychedelic era.

The Political Connection

Talking about the Boom is also talking about Latin American politics. Its writers were immersed in the turbulent political times of the subcontinent in the 60s and 70s, and saw themselves as public intellectuals and their works as pieces in that struggle. The most relevant political event of the time was, of course, the beginning of the Cuban revolution, and many have seen a connection between the attention that it brought to Latin America and the interest generated around the world by this new crop of writers. (Once again, the parallel with the Beatles rings true: music historians have suggested that Beatlemania was hyped by British newspapers to cover the embarrassment of the Profumo affair.)In many cases that connection was more direct: many of the Boom writers openly supported the Castro regime, most notoriously Gabriel García Márquez. But even when the Colombian writer never severed his ties with his close friend Fidel Castro, some of his fellow Boom members did (Vargas Llosa was among the first, and this political twist took him all the way to run for the Peruvian presidency as a liberal right wing in 1990). For many, the end of the infatuation with Castro began with the arrest of Cuban poet Heberto Padilla and his wife in 1971, an act of repression whose repercussions among intellectuals some have signaled as the end of the Boom itself. The disenchantment of the Boom writers with Castro and a sector of the Latin American left was also masterfully narrated in Persona Non Grata (1973) by Chilean Jorge Edwards, an account of his three months as ambassador of Salvador Allende in the island.

Macondo versus McOndo

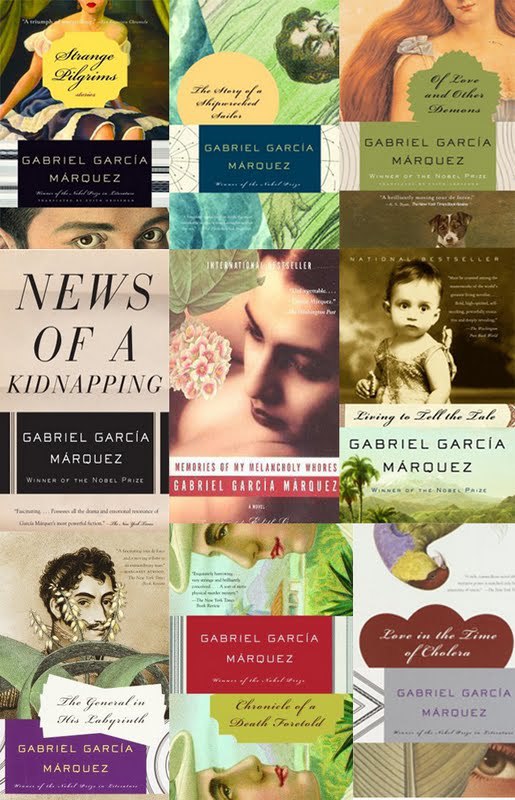

Even when the Boom reached its peak in the late 60s and early 70s, its effects were still being felt well into the 80s, a decade in which García Márquez received the Nobel prize and published his last great novel, Love in the Time of Cholera. Even though most of their writers would never publish another masterpiece, no identifiable generation had taken the relay of expanding the boundaries of Latin American Literature. This began to change towards the end of that decade and the beginning of the 90s, when authors like Chilean Alberto Fuguet, Argentines Rodrigo Fresán and Juan Forn, Peruvian Jaime Bayly and Bolivian Edmundo Paz Soldán published their first short stories and novels. The world they presented was more embedded in pop culture and a fast-globalizing world than that of their literary antecessors, and more apolitical than socially committed. In 1996 Fuguet co-edited the anthology McOndo, that gave the new generation a playful and global-friendly title, while reminding the members of the Boom that their days were, indeed, numbered. The feat made Fuguet the face of this dismembered bunch, famously propelling him to the cover of Newsweek in connection with a 2002 article in which the magazine asked if magical realism was dead.

Five Essential Books

1. The Death of Artemio Cruz by Carlos Fuentes (1962)

Fuentes' exploration of death, power and corruption is still one of the best gateways to appreciate the innovative techniques of the Boom writers as well as to understand the history of Mexico.

2. Hopscotch by Julio Cortázar (1963)

Even though some of the romantic undertones of this novel set in Paris may have not aged well, the radical inventiveness of Rayuela's structure is still mind-blowing — a novel designed to be read from beginning to end or in an alternate order. (Also, if you didn't have a college classmate that identified herself with La Maga, or no one tried to seduce you with its irresistible depiction of a kiss in chapter 7, you probably didn't grow up in Latin America.)

3. One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García-Márquez (1967)

One of the definitive works of Latin American literature; the unmatched book that inspired a million imitations and created a myth —that of MacOndo and the Buendías— so powerful that it's still affecting the way Latin Americans see ourselves.

4. Conversation in the Cathedral by Mario VargasLlosa (1969)

Vargas Llosa's equally unsurpassed answer to García Márquez's masterpiece. A conversation in a bar during the Peruvian dictatorship of Manuel Odría that ends exploring the darkness in all of our souls. A book in which Vargas Llosa shows his masterfulness by writing its four sections in different styles.

5. The Obscene Bird Night by José Donoso (1970)

An exploration of our identities and fears so dark and multi-layered, that it will haunt your dreams years after you have forgotten what its plot was about.