The Story of How a Puerto Rican Jew Jump-started Hip-Hop

Hip-hop started with Nuyorican Benjy Melendez and his band of Ghetto Brothers.

Dec. 18, 2012— -- It happened a little over 41 years ago, in the middle of a South Bronx park—a moment that would change Beny Meléndez, his street gang and rock band the Ghetto Brothers, and music history forever. When you hear him tell it, he sounds like it was only yesterday.

"My brothers came in the afternoon and we started playing music. 'I'm Your Captain,' by Grand Funk Railroad'," said Meléndez, vocalist for the Ghetto Brothers. "Then they told me some other gangs were looking for the Roman Kings and they're beating up people on the way here. I looked at Black Benjy and said, 'Take seven or eight Ghetto Brothers, no weapons, get me the leaders and bring them to me.' About half an hour later a guy comes running in, saying, 'They're beating up Benjy!' I said 'Move it, let's go!' We walked up 163rd Street to Stebbins Avenue, down Horseshoe Park. When I got to the bottom of the stairwell I saw his blood - oh God!"

Lying dead in the park that day was Cornell Benjamin, a.k.a Black Benjy, who had become Meléndez's (a.k.a Yellow Benjy) trusted lieutenant. But instead of lashing out with violence in revenge, Meléndez instead called for a peace summit with other gang leaders, and the Ghetto Brothers were transformed from roughneck turf-protectors to political organizers who helped set the stage for the dawn of hip-hop.

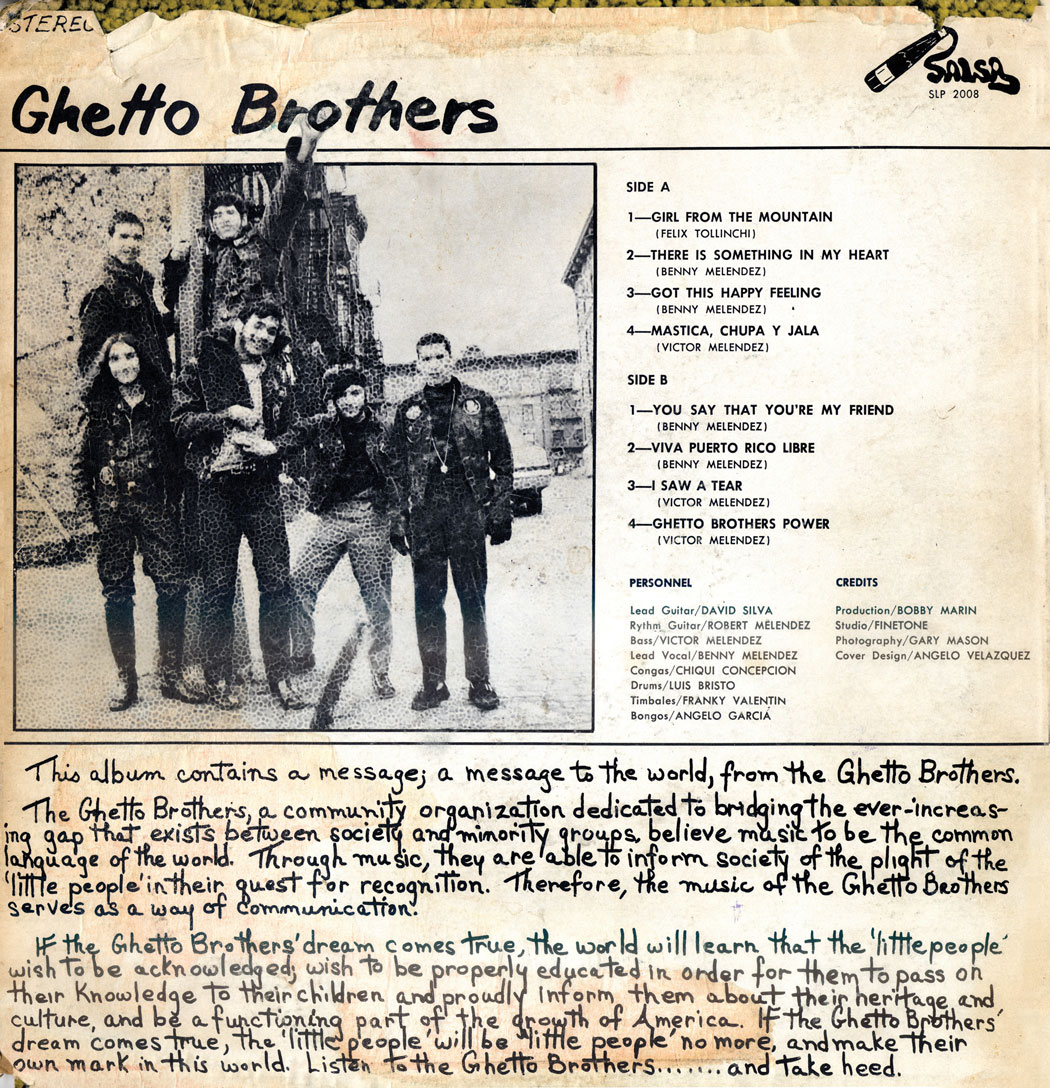

At first glance, Benjy Meléndez's story seems familiar and uncomplicated. Having been one of the major leaders of Bronx street gangs such as the Savage Nomads, Savage Skulls, and the Ghetto Brothers, Benjy and his banda of brothers (Robert and Victor Meléndez, who has since passed away, along with Chiqui Concepción, Luis Bristo, David Silva, Franky Valentin, and Angelo Garcia) eventually gave up the gang life to focus on music. The original line-up back then was Benjy on lead vocals, Benjy's brother Robert on rhythm guitar, Benjy's cousin Victor on bass, Chiqui Concepción on congas, David Silva on lead guitar, Angelo Garcia on bongos, and Franky Valentin on timbales.

But their music, seminal Latin rock, was recorded independently, got lost in the shuffle, and now, 40 years later, the only album they ever recorded, Power Fuerza, has been re-released by Truth and Soul Records for a new generations of listeners.

It's another Sixto Rodriguez story, this time about Puerto Rican rockers in New York, not a Chicano from Detroit.

See Also: The Story of Rodriguez, the Greatest Mexican American Rock Legend You Never Heard of

While Rodriguez, the subject of this year's acclaimed documentary Searching For Sugar Man, was more in the Bob Dylan cantautor (singer/songwriter) mode, the Ghetto Brothers were a collective ensemble whose music was driven by staccato rhythm guitars, Afro-Cuban percussion, '60s funk, and doowop-style vocals. They were a jam band ( that at times evoked bands like Sly and the Family Stone, the original Mothers of Invention, pop psychedelia like Vanilla Fudge, and of course, the Beatles. While their signature track "Ghetto Brothers Power" blatantly borrows from Sly's "Wanna Take You Higher," it is an individual statement from the streets of an urban ground zero that was literally burning to the ground from almost daily arson fires.

There is plenty of sentiment here, from the bugaloo doowop "I Saw a Tear," to Brit-pop cha-cha-cha of "There Is Something in My Heart." But the recording's strength lies in the band's freewheeling jams like "Got This Happy Feeling" which somehow seems like a precursor to both Fela's Afrobeat and the suburban post-punk of the Feelies.

According to Meléndez, the song was the result of a happy accident. "The recording engineer said 'mira, you got one more song, you gotta do it.' " So I said "we don't have any more songs," and my brother said, "listen, you got this 'Happy Feeling,' and I said, 'but I never finished the song.' So he said, 'man, just say anything.' So when you hear that I start laughing because I just said anything."

The original 1971 Power Fuerza album's back cover.

It was this spontaneous spirit of improvisation that allowed Meléndez and the Ghetto Brothers to shift gears when confronted with the death of Cornell Benjamin. In this excerpt from the '90s documentary Flying Cut Sleeves, by Henry Chalfant and Rita Felcher, Melendez explains how and why he called for a peace summit between warring gang members. Jeff Chang's 2005 book Can't Stop Won't Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation further documents that one of those present in the South Bronx Boy's Club that day was Afrika Bambaata, who was inspired to throw the parties in his neck of the borough that most historians agree was the basis for the birth of hip-hop.

Interestingly enough, the Benjy Meléndez connection reveals an unexpected truth about hip-hop, that although it has evolved into a genre that seems disconnected from rock and mainstream American culture, its roots were at least partially affected by a New York Puerto Rican rocker who was also Jewish.

"My family were descendants of marranos from Spain," said Meléndez, referring to the derogatory word used to describe hidden Jews in Spain and Latin America. "My father would draw the curtains and read from the scriptures, then he would send us to the streets to play on Saturday, so no one would get the impression that we were Jews."

In the 1980s Meléndez became active in a synagogue in the South Bronx. "A woman in the synagogue asked my name and I said 'Meléndez' and she said, 'that's not Jewish, that's Spanish.' And I said 'what's your name?' and she said 'Epstein,' and I said, 'that's not Jewish, that's German.' She came up to me and apologized later."

Meléndez's fascination with California motorcycle gangs induced him to set a new trend for wearing colors that set the standard for inner city youth gangs of the '70s.

"One day I saw a film with some friends of mine called Hells Angels on Wheels. When I saw the Hell's Angels [rockers gang on the movie] and I saw their colors, I said I can do that!" said Meléndez. "I went to the fabric store and bought some felt. I cut out rockers. I went to Harry's on Southern Boulevard, bought the letters, ironed them on to the rockers and then painted a logo on the felt and then everything was sewed onto the jacket. From then on, a lot of groups started to do the same thing."

The iconic Ghetto Brothers 'flying cut sleeves' vest.

A lot of the old guys had leather jackets. They had the colors but they were on leather. So since I wasn't riding motorcycles, I said let's put them on Lee jacket." The phrase "Flying Cut Sleeves" Meléndez attributes to Black Benjy, who was referring to the act of wearing denim jackets with the sleeves cut off, sporting the colors of your gang.

But Meléndez's affection for the Hells Angels dissipated when he went to their headquarters in New York's East Village to try to join. "I found out later that they don't accept black members. When they told me that I was shocked and I just left."

Soon after the gang peace summit, Meléndez was visited by a Black Panther organizer named Joseph Mpa. "He told me, why don't you take all this energy and do something constructive in the community—brothers can't be killing brothers," said Meléndez. "I had a meeting with the presidents, vice-presidents, warlords of all my divisions and I said 'I'm going to change the platform, brothers.' We're going to take off our colors, we're going to start wearing berets, and we're going to start cleaning our community, taking out the drug pushers, start giving out free food…"

Meléndez then began a long association with United Bronx Parents, a social service organization run by local hero Evelyn Anotinetty, and also made a commitment with activists for Puerto Rican independence. If you listen to "Viva Puerto Rico Libre," from the re-release, you can hear that Meléndez, unlike prototypical Nuyoricans, has a strong command of Spanish, giving this impromptu anthem a feel of authenticity that anticipated the political edge of much of '70s salsa.

But although Meléndez was a central force in creating the street collectivity and party atmosphere that inspired hip-hop, he did not have a strong connection or understanding of the phenomenon. "The Ghetto Brothers used to play every Friday night after the peace treaty, after the death of Black Benjy," said Meléndez. "Afrika Bambaata saw this and took it to the next level. When I saw it for the first time, guys dancing, I looked at my brother, and said, 'they look like the Pentecostals because I saw them turning in circles, that's the way I saw them in church.' So my brother said, 'no Benjy, that's called hip-hop!' They looked at me and said 'what is wrong with you?'!"

Benjy Meléndez in the 1970s.

The rock legacy of hip-hop is carefully hidden, but in some ways obvious. You can hear it in one of hip-hop's first classics, Bambaata's "Planet Rock," which samples the visionary German band Kraftwerk, The Treacherous Three's "Body Rock," or The Strikers' lesser-known "Body Music," which urges you to "rock, rock to the punk rock." But that little snippet, as well as Nuyoricans' crucial role in contributing to graffiti-writing, break dancing, and DJing, have become an afterthought.

In the early '80s, as hip-hop began to hit its stride, the Ghetto Brothers had reinvented themselves as the short-lived Beatles imitators Street the Beat. "We once opened up for Tito Puente as the Junior Beatles," said Meléndez, who started singing with the band at age 11, and has played consistently with them since. Street the Beat played Beatles covers on Greenwich Village street corners and according to Meléndez, played private parties for the Rolling Stones, the Police, and Hollywood celebrities. "Diana Ross walked up to me when I was playing and put $100 in my pocket!" he recalled.

Since then, it's been a struggle for Benjy, who, at 60, suffers from kidney failure and has been on dialysis. Though he worked as a counselor at United Bronx Parents for 30 years, he had to stop working last year due to this health. Around the time he started working as a counselor, he met and married his second wife, Wanda, with whom he has six kids - and two more from his first marriage.

Despite his health concerns, Meléndez is very enthused about the sudden rebirth in interest in the Ghetto Brothers - the result of an accumulation of things. Chang's Can't Stop Won't Stop book, anappearance by the Ghetto Brothers at the Experience Music Project conference in Seattle in 2004, and Meléndez appearing with Afrika Bambaataa at various speaking engagements throughout the last decade. But the band - currently comprised of Benjy on vocals, Benjy's brother Robert on rhythm guitar,Benjy's son Joshua on lead guitar and bass, and Robert's son Hiram on drums - is about more than just nostalgia these days. "We have a totally different sound now, we practice in the studio constantly," said Meléndez. "We're hoping we can go on tour soon and record a new album."

He's just happy for that day in 1971, when he decided to take off his colors for peace. "I dropped the Savage Nomads and somebody else took over, and I dropped the Savage Skulls, because if I wore the jacket that said Savage I had to back it up. So I was a Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. As soon as I put on those denims I had to act out that name," said Yellow Benjy. "So I just stayed with the Ghetto Brothers."