How Do We Know There Are 11 Million Undocumented?

Breaking down figures from the Pew Hispanic Center.

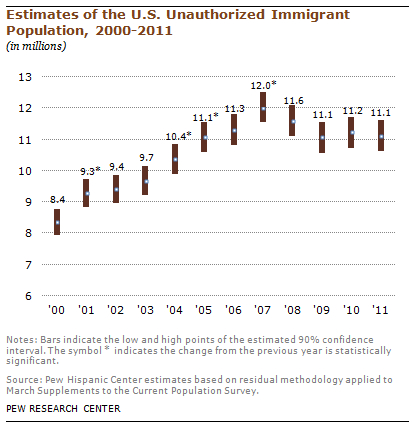

Dec. 6, 2012— -- If the early talk about immigration reform is any indication, one of the major political battles in 2013 could be over what happens to the 11 million undocumented immigrants living in the U.S.

But how did we come up with the 11 million number?

The figure actually comes from the Pew Hispanic Center, a research institution. The center's chief demographer, Jeff Passel, has been crunching numbers like this one for more than three decades.

"Back around 1980 or so the conventional wisdom of the time was there were 6 to 12 million unauthorized immigrants living in the country," Passel says. "That was both very wide and very wrong."

See Also: 23 Defining Moments in Immigration Policy History

A lack of data and no precedent made it hard to be more accurate. But when the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, also known as the 1986 amnesty, created a broad pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, it also provided an opportunity to see what methods were working.

Roughly 2.6 million immigrants legalized through the one-year program, and Passel's team had estimated 2.5 to 3.5 million. That validated their methodology, he says, and since then, "the range of estimates has shrunk substantially."

So what does the methodology look like? Experts will cringe, but here's a plainly written explanation of the formula Pew uses to make its projections:

X (total immigrants counted in survey) - Y (legal immigrants) + U (correction for undercount) = Z (undocumented immigrants).

The starting point is the Current Population Survey, a monthly employment survey by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. The survey asks people where they were born and when they came to the U.S. That gives demographers an estimate of the total number of immigrants in the country, counting those with and without papers. So that's how they come up with the figure for X.

Demographers know the number of legal immigrants from statistics compiled by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. This is the figure for Y.

Naturally, a group of people who tend to live below the radar might not be eager to speak with survey interviewers, even if they're not being asked about immigration status. This is why Pew also adjusts for an undercount .

Adjusting for the undercount is when things get tricky. X (total immigrants in survey) - Y (legal immigrants) = the number of undocumented immigrants counted in the survey. But how many undocumented immigrants does the survey miss?

Pew says you need to increase the X - Y figure by 10 to 15 percent to combat the undercount. That means that if the survey count shows 10 million undocumented people in the U.S., you would add 1 to 1.5 million to that number to compensate for people who aren't counted.

And if you're wondering how they decide on the percent to factor in, here's how.

First, demographers turn to Mexico, since Mexicans make up 55 percent of undocumented immigrants, according to a recent Pew Hispanic Center study.

They look at how many people were born in Mexico 25 years ago. Then they find out how many of those people are still in Mexico today and how many are in the U.S. legally. A chunk of the people born in Mexico 25 years ago won't be accounted for in either country. That figure helps inform the estimated number of undocumented who might have been missed in the survey.

Pew cross-references that figure with several studies looking at populations undercounted in censuses. One study co-authored by Enrico Marcelli, an assistant professor of sociology at San Diego State University, showed that while the vast majority of people participate in the census, undocumented immigrants were the least likely group to participate. So Pew factors that into their undercount estimate.

The data isn't perfect. Even Marcelli, whose report helps guide the estimate, told The Wall Street Journal in 2010 that he didn't think his numbers -- which look at Mexicans living in Los Angeles -- should be applied to a national formula, but agreed that demographers do not have any other empirical evidence at the moment with which to proceed.

Passel says that if considered along with several other types of data -- including the Mexican population figures -- demographers can get pretty close to a solid answer.

Still, Pew factors in a margin of error ranging from 300,000 to 500,000.

Although demographers seem to be getting better at estimating the number of undocumented, a mass legalization program in 2013 could provide an affirmation that the current methods are on track. As it stands, the current estimates still inspire debate, but they're much better than the numbers that were floating around in the early 1980s.