Deported by Association: American Follows Husband to Brazil

Rachel Custodio moved to Brazil after her husband’s deportation.

Aug. 26, 2013— -- Four suitcases.

That’s what remained of the life that Rachel Custodio had shared with her husband, Paulo, in their two-bedroom apartment outside of Boston. Everything else had been sold, given away or stored at her parent’s house after she learned Paulo would be deported.

Clothes, shoes, toothpaste, deodorant, razors. She was only bringing the basics to Brazil.

Her stomach knotted as her parents drove her to the airport. She had literally trembled with fear the few times she had flown on a plane, but that afternoon in October 2010 was even worse.

She had never left the U.S. and she didn’t speak Portuguese, aside from a few phrases. Now she was traveling alone to meet Paulo, who had been escorted out of the country in handcuffs and shackles days before.

As she boarded the plane, she had no idea when she would be coming back.

Nearly three years later, she still doesn’t know.

The Marriage Test

Rachel Custodio is part of a group of people who usually aren’t mentioned when we talk about immigration policy: U.S. citizens married to undocumented immigrants.

The Obama administration has deported more than 1.6 million people, a historic high. But those deportations don’t just affect the people who are removed; they can be life-changing for the children, parents, and spouses who are left behind.

Statistics aren’t available for the exact number of spouses who follow their deported husbands and wives out of the country, but the phenomenon has likely been on the rise as removals have skyrocketed in the past decade.

We do know that families are being broken up through deportations. In the first six months of 2011 alone, more than 46,000 fathers and mothers of U.S. citizens were removed from the country, according to a report by the Applied Research Center, a racial justice think tank.

In the case of Rachel and Paulo, they were trying to do things “the right way.”

They married in April 2009 but knew that Paulo’s immigration status would need to be resolved eventually.

He had crossed the border illegally seven years earlier, a $4,000 trip with gun-toting coyotes and a brutal desert march from Mexico into Texas.

“I remember they give you a jug of water, like a gallon water, and I just suck it in,” he said. “I didn’t know that you should drink slowly.”

During several nights in safe houses in Houston, coyotes guarded his group of nearly two dozen migrants with guns, making sure no one tried to flee. The people being smuggled had only paid a portion of the fee, so the coyotes wanted to make sure no one would disappear before the balance had been settled in full.

From Houston, a van drove the migrants to different locations. Paulo went to the Boston area, where he had family and eventually found steady work as a roofer.

In 2005, he met Rachel, then 22, at a nightclub called Rain in Malden, Massachusetts. They both had noticeable accents: Paulo, his English decorated with strings of Brazilian vowels; Rachel, with the characteristic New England tone that turns a “car” into a “caah.”

After dancing at the club, they exchanged numbers and started dating.

“He was genuinely interested in everything about me,” she said. “We would talk for hours on the phone, sometimes until the sun came up.”

After they married, the couple hired an immigration lawyer and began the process of straightening out Paulo’s immigration status. Even if everything went according to plan, Rachel says that she knew Paulo would have to return to Brazil at some point and apply for a visa from there.

The first step they had to do was an interview with immigration officials where they would essentially prove that they were married.

They expected to be peppered with a range of questions, from things as general as where they met to hyper-specific details like the color of their spouse’s toothbrush.

For Rachel and Paulo, however, the problem wasn’t the marriage test.

In May 2010, they went to a federal office building in Boston for what was known as the I-130 interview. The tone of the appointment soon went from technical to investigative, though.

“Before we knew it, the immigration officer said he had to go talk to a supervisor,” their lawyer, Christina Corbaci, recalls.

Corbaci says she looked at a file on the officer’s desk and suspected that Paulo had an immigration record that the couple wasn’t aware of. “I told him, ‘You know, I think that you do have a deportation order, and I think that they’re coming to get you.’”

Someone else in this situation might have left the building, but Paulo decided to stay. An officer with U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) appeared and told him that he would be taken into custody.

Rachel was panicking, crying.

“I was thinking it was a mistake or something,” she said. “That’s what we were all thinking.”

A Costly Mistake

Paulo says he was totally oblivious to the deportation order. There’s reason to believe him: if he knew about the order, then why would he have walked into a federal immigration office and exposed himself to authorities?

The story, according to the Custodios and their lawyer, is that an acquaintance of Paulo’s offered to get him a driver’s license.

In most states, undocumented immigrants aren’t eligible for licenses. Still, lots of people drive, licensed or not. Paulo was one of those people.

His van was registered to a friend and he paid insurance, but he didn’t have a license. He worried about getting tickets or even worse -- getting pulled over and then having a police officer discover his immigration status.

That’s where the acquaintance came in. He was another Brazilian, but a Florida resident, according to the Custodios. He filled out paperwork for the license on behalf of Paulo, and then Paulo went to a motor vehicle office in Fort Lauderdale, where he was able to get a license. The whole thing cost him $150, he says.

What Paulo says he didn’t realize was that in order to get him the license, his friend also submitted an application for a work visa. That application could be used as proof of identification, along with his Brazilian passport.

"I did not speak English very well back then, so I didn't review all of the papers he gave me at the time because I didn't understand them," Paulo later stated in court documents related to his case.

The visa application put him on the radar of immigration officials, though, who sent him a notice to appear before an immigration judge. Paulo says he never got that letter, and that it likely went to the friend’s address in Florida.

He failed to appear for a related court hearing and a judge ordered his deportation, in absentia.

Deportation Priorities

Paulo handed Rachel his wallet and whatever else he had in his pockets. The ICE officer wanted to put him in handcuffs, but Paulo says he spoke with him and asked if he could go without them. He didn’t want to look like a criminal.

Within minutes, he was gone and Rachel was left in tears, standing with Corbaci, her lawyer.

“It was the worst day of my life,” she said. “It was the worst day of both of our lives.”

Deportation policy isn’t static; it can change depending on the approach of a particular president or administration.

For example, a policy shift during President Obama’s first term revolutionized the way immigration officials pursued removal cases.

On June 17, 2011, John Morton, then the director of ICE, issued a memo that asked immigration agents to use “prosecutorial discretion” when deciding which immigration cases to follow up on.

The memo gives agents the power to focus on high-priority cases -- and ignore low-priority cases.

Corbaci believes that Paulo’s case could have qualified for prosecutorial discretion.

“Our experience is the prosecutorial discretion policy, at least up here in Boston, I think he probably would have qualified,” Corbaci said. “They list all of these factors that are positive and negative, and immigration fraud is obviously a negative, but I think it would have been minor considering his minor role in it.”

ICE disagrees.

Spokesperson Khaalid Walls wrote in an email that Paulo was considered “an immigration fugitive” -- a judge had ordered his removal and he had, in the eyes of the law, ignored it. That meant that he fell within the agency’s priorities for deportation, another spokesperson told Fusion.

In other words, he may not have been a criminal, but ICE still considered him a priority to be removed from the country.

Detained Without Parole

During the early days of Paulo’s detention, Rachel was hopeful that he might be released.

She took a week off from her job as a staff accountant at a local dialysis center and moved in with her parents.

“The first week he was in there, they were saying we might be able to get him out possibly by getting character references from people,” Rachel said, explaining her lawyer’s strategy. “They could put an ankle bracelet on him.”

She rounded up letters from family, friends and coworkers of Paulo’s, about ten people in all. But within two weeks, immigration officials told them that he wouldn’t be eligible for parole, she said.

In the past decade, fewer immigrants have been granted temporary release after being picked up by federal authorities. Instead, they’re held for future hearings or eventual deportation.

Alternative supervision would be cheaper, but in many cases, immigration judges don’t have the authority to grant it to detainees. One federal immigration official told Reuters earlier this year that the daily cost of holding a detainee is $119 per day, compared with anywhere from $0.17 to $18 if the person is released and supervised.

Since they’d been married, Rachel and Paulo had never been apart for more than one night. Now she could only visit him once a week, for an hour.

Each Sunday, she would travel to the jail and sit with him, unable to act affectionately like they would have in the outside world. “You could just hug,” she said. “You couldn’t give him a kiss or anything.”

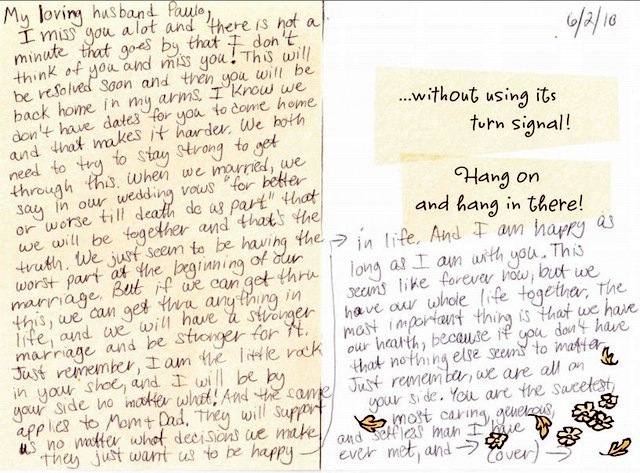

A card that Rachel sent to Paulo while in detention. (Courtesy of Rachel Custodio)

She aligned her life around those visits and his daily phone calls. Since she wasn’t allowed to call him, she would need to be on standby, waiting for him to call three times each day.

On the phone and during the weekly visits, Paulo told her about detention: how the air conditioning only seemed to work 50 percent of the time, making it stiflingly hot otherwise; how he developed a rash on his elbow, probably because of the heat, but couldn’t get medical treatment for a week; how he helped correctional officers break up a fight in the jail, only to be threatened by several other inmates afterward; how one correctional officer told him, “I am your God” after he saw Paulo and other inmates praying.

Months passed and their case made no progress. “We didn’t want him to have to stay there any longer,” Rachel said. “And the chances didn’t look good.”

A Humiliating Feeling

After a little more than two months in detention, Paulo agreed to be removed from the county. He was deported to Brazil two months later, on October 5, 2010.

He had no criminal record and had never been charged or convicted of a crime. Yet when he was removed from the country, he was put into a van and placed in a secure seat that reminded him of a dog cage, he said.

Even Paulo, who was 5’5”, says he hit his head and knees on the metal dividers that separated detainees. He endured that during the four-hour ride from Boston to New York City, where he would be flown out of the country.

The ride made him physically uncomfortable, but he was more bothered by how others might perceive him.

“The worst part is when you go to the airport, you have handcuffs on your hands, and you have everyone watching you,” he said. “That was humiliating.”

While Paulo boarded his flight out of the country, Rachel was getting ready: from the moment she realized he would be sent to Brazil, she decided to follow him there.

“He’s my husband and we got married to be together, we made a commitment to each other,” she said. “You don’t really have much of a marriage talking through webcam and on the phone.”

She was more worried about how their relationship would hold up if they had to spend five years living on different continents.

“What if you end up drifting apart, somehow getting a divorce?” she said. “It’s happened to people.”

Deported By Association

In Brazil, Rachel likes to go jogging around her and Paulo’s apartment, but he won’t let her go after dark. As it stands, he gets nervous about her going at all.

“We don’t live in a bad area but you never know,” he says. “I’m worried, you know, especially if something happens to her, I’m going to feel it’s my fault.”

Their new home is a building in downtown Tubarão, a relatively small city of about 93,000 people in the southern Brazilian state of Santa Catarina.

While her Portuguese has gotten better, she’s still far from proficient. Paulo acts as her translator most of the time.

Rachel says she’s never seen another American in Tubarão, so she can’t meet up with fellow ex-pats the way she might be able to if they lived in a larger city.

To hear her describe it, her time in Brazil has been less of a vacation and more of a psychological endurance test.

“Sometimes I didn’t even want to go out because I can’t talk,” she said. “I’d stay in.”

Paulo knows that it’s hard for her to socialize when she doesn’t speak the language.

“A few times I caught her crying from out of nowhere,” he said. “I’m putting her in this situation, that’s how I feel...I dragged her here with me.”

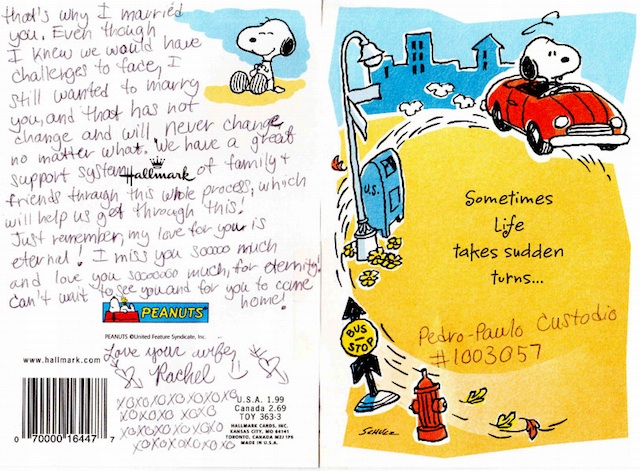

A testimonial written by Rachel's uncle while Paulo was in detention in Boston.

Still, it’s not all bad. They go out to restaurants and take trips to the beach. Rachel continues to marvel at the beautiful mountainous terrain you see when you’re driving through the county.

And she’s had a chance to spend time with Paulo’s family, even if there’s still a language barrier. She wants to be with her own parents, but is glad to have his relatives for support.

“My family is there, but I have his family here, and him,” she said. “It’s kind of like you’re torn in the middle.”

Work is a legitimate concern, though. Rachel is able to teach English online, but she’s making about $12,000 per year, compared to the $48,000 salary she had in Massachusetts. Paulo went from making $200 a day as a roofer and contractor to bringing in $50 daily.

Things like food and rent are cheaper, but other items, like disposable razors or electronics, are more expensive than in the U.S.

Paulo's extended family in Brazil. (Courtesy of Rachel Custodio)

They’ve also put their own relationship on hold. They’ve talked about having kids, but they want to wait until they’re back home. Rachel doesn’t want to raise a child on the salaries that they’re making.

“We were going to wait until we came back, but I don’t know how much longer it’s going to be,” she said. “I hope I’m not too old.”

When Paulo agreed to leave the country and stopped contesting his case, he also accepted a punishment within the immigration system.

He would be banned from returning to the country for 10 years, because of three separate charges. The issues: failing to appear for his immigration hearing, spending more than a year in the U.S. without authorization and being subject to deportation.

The first step will be waiting out a five-year bar -- the one he received by failing to appear at his immigration hearing, according to his lawyer. Unless they can reverse that, it will take them to 2015.

If they can’t successfully appeal the 10-year ban after that, they could be in Brazil until at least 2020, and likely longer, considering the time it will take them to acquire his visa.

Family Left Behind

The effects of Paulo’s deportation carry back to Massachusetts, as well.

As an only child, Rachel was close with her parents, Debra and Milton. She and Paulo lived 15 minutes away from them, and they would visit frequently and help them with chores around the house.

The visits weren’t just about keeping her parents company. Rachel’s mother has had serious health problems, including four separate bouts of cancer and knee replacements that make it difficult for her to get around on her own. Rachel and Paulo would help them around the house and drive them to doctor’s appointments.

Months after Rachel moved to Brazil, Debra was diagnosed with colon cancer. She was left to grapple with the latest in a string of illnesses without her only child.

“My daughter would be making meals and she would take me to appointments,” Debra said of her past illnesses. “And when she couldn’t, Paulo would.”

Oddly enough, the fact that Rachel’s parents depended on them could help their immigration case.

Rachel’s lawyer thinks that the 10-year ban for Paulo to return to the U.S. might be overturned if they could get an immigration official to consider the circumstances.

So far, however, that hasn’t happened.

Reasons for Hope

In regards to Paulo’s case, Khaalid Walls, the ICE spokesperson, issued this statement:

“Mr. Custodio was subject to an outstanding deportation order issued by an immigration judge in 2008 and was considered an immigration fugitive until his arrest in May 2010. In accordance with the final order of removal issued by the judge, he was removed from the country shortly after his arrest.

“ICE is focused on sensible, effective immigration enforcement that prioritizes the removal of criminal aliens and egregious immigration law violators.”

The immigration system might not offer them clemency, but there’s another hope for the Custodios. Congress could change federal immigration laws to allow some U.S. citizens to sponsor their deported spouses for visas.

A measure like this was part of a massive immigration reform bill passed in the Senate this June. But leaders in the Republican-controlled House of Representatives have said they won’t take up the legislation, and it’s unclear if they will pass something comparable to the Senate bill.

There’s no promise that a bill will pass this year, or anytime soon. Congress hasn’t passed legislation like this in decades.

Paulo and Rachel are aware that a change in immigration laws is a longshot.

“I’m putting everything on hold,” Rachel said. “My career’s on hold, my family’s on hold.”

“We feel like we’re just waiting.”

Update, Aug. 29, 11:05 a.m.: I originally wrote that Paulo spent four months in detention before accepting his deportation. He actually spent a little more than two months before making that decision.