Happy Birthday, DACA: Program Offers Hope for More Limits on Deportations

DACA shows why a moratorium on deportations could work.

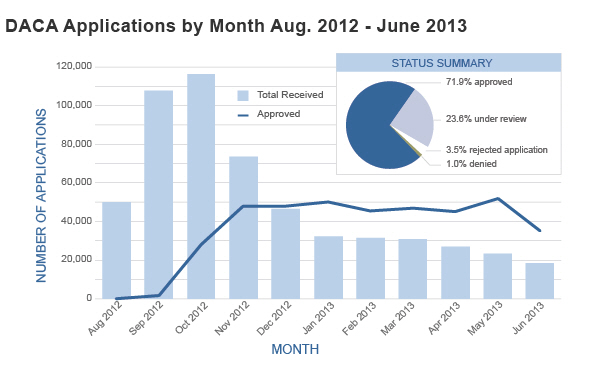

Aug. 14, 2013— -- More than 400,000 young people have been granted deportation relief and given work permits under an Obama administration program that began on August 15, 2012.

The program, called Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), enables young people who were born abroad but raised in the U.S. to more fully contribute to their communities, economically and otherwise.

Despite many success stories, it’s also been controversial.

DACA wasn't passed into law by Congress; it was an executive action by the Obama administration.

The idea is that the executive branch has the power to decide how best to use its resources. And deporting young people with good standing didn't seem like a smart use of those resources.

Republicans haven’t been happy about the move, which bypasses Congress. In June, nearly all of the Republicans in the House of Representatives voted to defund the program. The vote was symbolic -- there was no chance of such a measure passing the Senate -- but showed that the GOP rank-and-file didn't approve.

This week, Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) sent a warning message to his party, saying that if they didn't pass some sort of immigration reform legislation, Obama might expand the DACA program to all of the estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants in the U.S.

An action like that would irritate Republicans in the House, but, if anything, DACA proves that a broader deportation relief program could be a success.

First, there are the anecdotal stories that DREAMers tell about how the program has impacted them.

Fusion compiled 50 of them here, but there are hundreds of thousands more. Clearly it’s had a positive impact on many of those who have applied and been approved.

You can also look at the data from the year that the program has been in place. The Brookings Institution, a center-left think tank, has broken some of it out into charts.

First of all, only about half of people who were estimated to be eligible for the program have applied.

That means there are likely some impediments keeping people from accessing deportation relief. But it also shows that there wasn't some sort of mad rush of millions of people once DACA became available.

Some people who oppose “amnesty” for undocumented immigrants use the mad-rush theory as a counter-argument -- that millions more will apply than expected. But DACA proves that wrong.

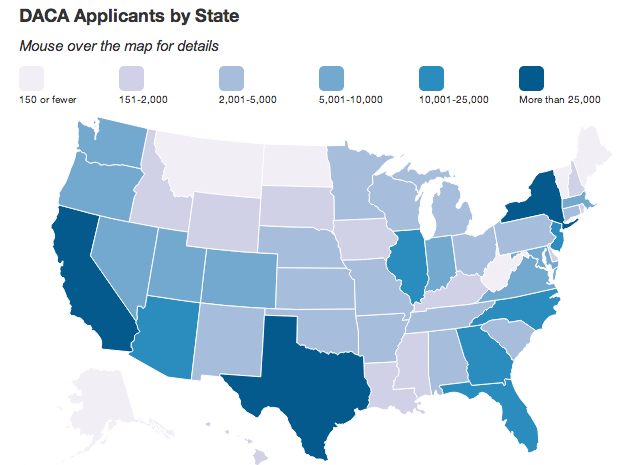

And then there are the states where most of the DACA applicants have come from: New York, California, Texas and Illinois -- places where there is strong support for immigrants rights.

Rep. Steve King, an Iowa Republican who is arguably the most vocal opponent of DACA in Congress, hails from a state where less than 2,000 people were granted deportation relief through the program. So while he might be one of the loudest voices in the debate, the program has a limited impact on his constituency.

In other words: his opinion doesn't really matter very much.

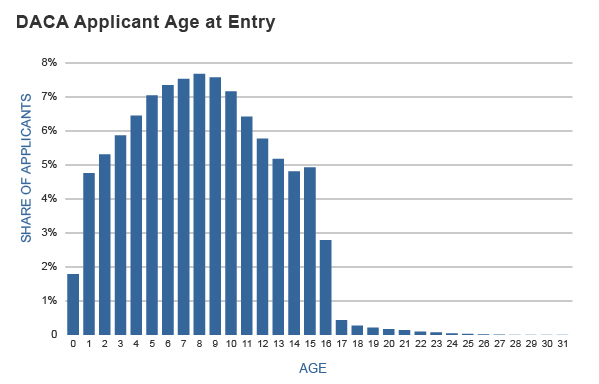

Here’s another telling bit of data. More than two-thirds of DACA applicants came to the country before the age of 10. Many of them likely traveled with a parent or family member.

That means that there are even more mixed-status families out there, where some people have legal status or deportation relief, but others are still living undocumented. That’s another argument for a broader deportation relief program.

We've given deportation relief to the young people in some families, but not to the other people they sit down with around the dinner table.