Hopeful,'Unapologetic' Art Rebrands the Immigration Movement

Activist artists are reshaping immigration.

March 1, 2013 — -- Every year, during their mating season, millions of monarch butterflies make the journey from Canada and the U.S. to a small town in Mexico called Angangueo where they coat branches and leaves like gobs of black and orange paint. Migration is built into the monarch's DNA. For that very reason, the creature has played a central role in the rebranding of the undocumented movement. The choice in symbol is simple: Migration is natural, borders are not.

Gallery: Art From the Immigration Movement

Whether it's plastered across buses, screened on t-shirts or painted on billboards, the monarch has spread quickly thanks in large part to a group of West Coast artists -- including Melanie Cervantes, Cesar Maxit, Jesus Barraza, Ernesto Yerena, Julio Salgado and Favianna Rodriguez.

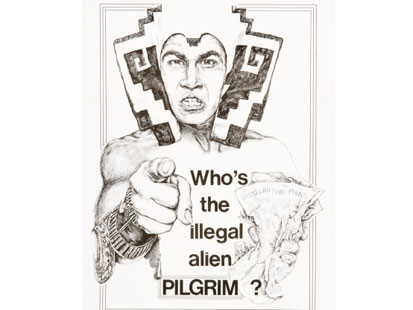

Through their work, these artists have helped shift the the movement by making art that reflects a more positive tone said Rodriguez, a California-based printmaker and activist. Phrases like "Undocumented and Unafraid," "No Papers No Fear" and "Migration is Beautiful" have grown in popularity -- a stark contrast from some of the movement's former posters which responded to the media's depiction of immigrants like, "Who's the Illegal Alien, Pilgrim?".

Yolanda Lopez made this poster in 1981. The reactionary tone of her work stands in stark contrast with the current movement's hopeful slogans.

Yolanda Lopez made this poster in 1981. The reactionary tone of her work stands in stark contrast with the current movement's hopeful slogans.

"It's about setting forth very positive messaging about who we are," said Rodriguez. "We're not politely asking for our rights anymore, we're demanding them."

Although the butterfly has been in use for more than a decade in various Latin American migration posters, it wasn't until the last year that artists began "popularizing the symbol" within the current immigration debate.

On July 29th of 2012, a group of more than two dozen undocumented activists gathered in Phoenix, Arizona and painted a 1972 sea-foam green bus, using monarch butterfly stencils and black and orange spray paint. They named the vehicle the "Undocubus" and traveled across the country, stopping in 10 states to protest the failures of immigration policy before the Democratic National Convention.

Although artists like Cervantes and Maxit used the monarch iconography in images protesting Arizona's SB1070, the painting of the Undocubus was a turning point for the symbol because it married the art to the members most associated with the debate. After appearing on the bus, the monarch started showing up in more artists' prints and paintings. A corresponding hand sign -- thumbs interlocked and fingers spread open like wings - also became ubiquitous in protest imagery.

"I think it's kind of like a logo now, a very affirmative shorthand logo for what the movement is positing," said Carol Wells, the founding director of the Center for the Study of Political Graphics (CSPG).

Wells says that shifting the narrative from one of "victimhood" to one of "empowerment" has been an important step in most protest art movements.

"If a movement is going to be successful, it can't just be negative all the time. There has to be this message of hope, like the one we're seeing now," said Wells.

In many ways, protest art has been for the immigration movement what music was for the civil rights movement of the 1960s.

'We shall overcome,' that was a pretty hopeful message," she said.

Much like the work of musicians in the 1960s, the work of artists has helped galvanize the base and bring new individuals into the immigration reform movement. Because the movement is multilingual and doesn't center on one language, imagery has been a particularly effective means for doing this.

However, unlike the civil rights movement, immigration reform has benefited greatly from the digital age. Powerful images and videos are shared across platforms, and "go viral" on sites like Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, and Instagram.

In the weeks following the January release of a documentary about the movement hosted by rapper Pharrell William's YouTube channel, called 'Migration is Beautiful,' Rodriguez has seen a new young wave of supporters persuaded to join the movement because of its art. As of publishing the documentary has more than 20,000 views on YouTube, and Rodriguez says she's heard from many young students who say they want to get involved in the advocacy movement.

"These are 14 and 15 year olds who see what we do and say 'Whoa! I want to be down with this,'" Rodriguez said. "Some of them had no idea that these things were happening in our country before seeing our art."

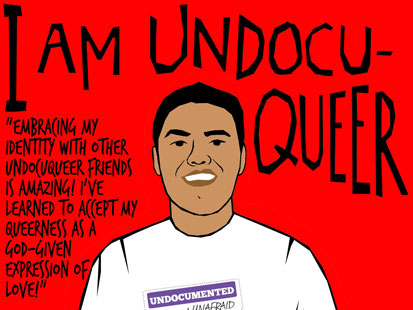

Julio Salgado, a 29-year old undocumented artist based in L.A., who is waiting for his DACA application to come through, says his work relies heavily on new technologies. Salgado's cartoonish images of undocumented faces often accompany posters protesting the deportation of or calling for justice for specific immigrant families. He is also an advocate of LGBT immigrant rights, and the term "Undocu-queer" appears in many of his works.

Social media has been a tremendous organizing tool for DREAMers, but also a way to share art and images, Salgado said.

"I used to think, 'I wanna go out and put my art on walls,' but, then of course, I said to myself, 'Damn, if I get arrested doing it, then that's a whole different issue for me," said Salgado, referring to his undocumented status. "So I started sharing my stuff on Facebook, and I got a huge reaction there and so I started a Tumblr and I've gotten so much support."

But new technology doesn't help overcome all the barriers facing the movement.

"You're not going to walk into a protest with your computer monitor, or on your lawn," said Wells. "Even in this hi-tech age, posters need to be printed."

And printing, of course, takes money. Although the immigration arts movement has exploded over the past two years, with more artists involved in the game than ever, finding funding is still a struggle. A few organizations like CultureStrike (organized by Rodriguez), the Opportunity Agenda and the National Association of Latin Arts and Cultures (NALAC) are helping to raise funds for artists in the movement.Rodriguez also believes the movement has a real lack of undocumented artists, who often struggle even more with securing funding and work due to their status.

"The political movement has changed in direction, and is now led by undocumented migrants who were once in the shadows. But, we have to ask how we can make the art movement reflect that shift." said Rodriguez, who took Salgado under her wing two years ago.

Art is integral to the success of the immigration reform movement, according to artists like Maxis, Rodriguez and Salgado. And having a symbol tied to the cause legitimizes the ideas of the movement in the eyes of the media and the public. Protesters accompanied by "beautiful" images are more convincing than those without them, says Rodriguez.

"Art is beautiful. It speaks to more senses than press releases and newspaper headlines," said Rodriguez. "The more we can turn a press conference into a performance art piece, by wearing butterfly wings, or showcasing our icon work, the better."

Pullitzer prize winning journalist and immigration reform activist Jose Antonio Vargas dedicated a lecture this week at USC to the importance of art in his fight.

"We need art in order to transcend the conversation that's become way too political," Vargas said.

The new brand of immigration protest art, however, doesn't only sway the apathetic and inform the ignorant. It also galvanizes members of the movement to continue the fight, according to Wells.

"Art reinforces the movement, it helps grow the movement, it creates the identity of the movement. It educates and it inspires," Wells said. "It cannot be underestimated."