Why Brazilians Are Angry Over World Cup Spending

The Brazilian Government has Spent Billions on Stadiums that Won't Be Profitable

June 19, 2013— -- There are many reasons why people have taken to the streets to protest in Brazil. And one of the main sources of discontent has been the billions of dollars spent on World Cup infrastructure in a country where poverty is still prevalent.

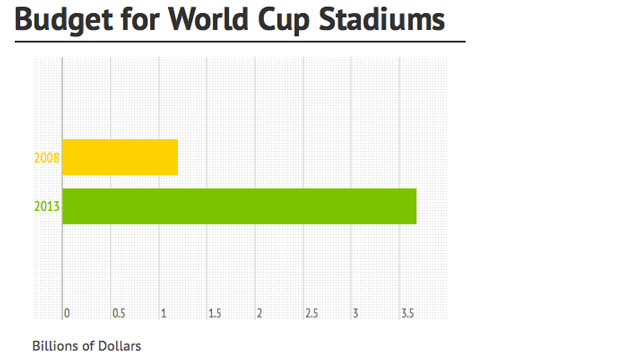

We looked at some figures on World Cup expenditures that help to explain why many Brazilians are angry at how their government has managed the World Cup. Just look at the graph below.

Brazil's estimated costs for renovating soccer stadiums or building new ones that will meet World Cup standards have tripled since the country was awarded the World Cup back in 2008. Most of that is due to corruption and economic inefficiencies, like high taxes, that make construction work more expensive.

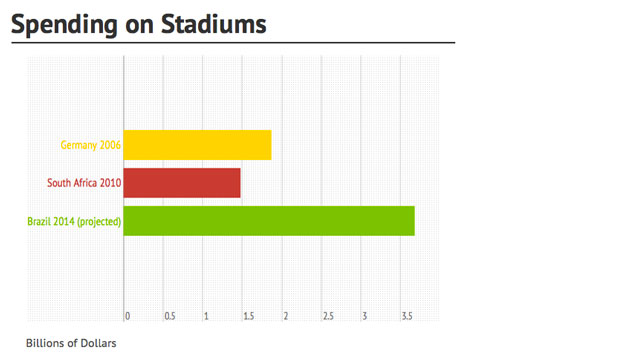

What Brazil could end up paying for stadiums is substantially greater than what South Africa and Germany invested when they hosted the World Cups in 2006 and 2010, respectively.

To make things worse for Brazilians there are several signs that many of these stadiums will not be of much use after the World Cup has ended. According to Reuters, anywhere from four to eight of Brazil's 12 World Cup stadiums will be "white elephant" projects that will never turn a profit.

That's is partly because some of these stadiums are located in towns where there are no first division soccer teams, or where there is little demand for massive events. For example, Manaus and Cuiaba, two cities in sparsely-populated areas of Brazil that have no first division teams, will each get brand new $200 million stadiums.

There are also other expenditures, like security, for which the government has budgeted $900 million dollars. And infrastructure improvement projects, like hotels, airports, roads, and transport networks, in which the government expects to spend an additional $12 billion.

So what does Brazil Gain from Hosting the World Cup?

The Brazilian government has commissioned several studies on the economic impact of the World Cup, which estimated that the tournament will add anywhere from $70 to $110 billion to Brazil's economy in a ten-year period that started in 2010.

The studies explain that some of this income will come from a boost in tourism and from the positive impact of infrastructure projects that are triggered by the World Cup. But these studies have come under scrutiny by some economists who say that the findings are politically motivated.

Dennis Coates, an Economics Professor at the University of Maryland, points out that tourism does not increase dramatically with big events like the World Cup. That's because while host countries are visited by thousands of soccer fans, they also lose regular tourists who want to avoid the crowds and high prices for accommodations that are generated by this kind of event.

Coates also notes that in 2006 revenues from tourism in Germany were only 60 million Euros greater than in 2005. That's a small amount if you consider that the country spent more than $1 billion just in stadiums. In Korea, which co-hosted the 2002 World Cup with Japan, the number of foreign visitors during the World Cup was almost identical to the number of visitors in the same period of 2001, according to Coates.

World Cup earnings are also hard to quantify. South Africa knows that. Two years after hosting the 2010 World Cup the South African government issued a report in which it said that it could still not put a number on the tournament's economic impact on the country. The report did say that South Africa would earn $6 billion from the Cup, but that was a mid to long term projection based on a series of unpredictable variables.

Who is the Winner in Brazil?

FIFA obviously wins. In South Africa, for example, the world soccer organization earned $2.4 billion from selling television rights to the World Cup and $1.07 billion from marketing rights. This income went straight to FIFA and not to the host country's government.

FIFA said, however, that it spent $1.2 billion on organizing the World Cup and used 70 percent of its earnings on smaller tournaments and soccer development projects around the the world, including a mayor soccer initiative that targets low income kids in Africa called "Win in Africa."

What this means is that in Brazil the World Cup will generate several winners and losers, as it did in South Africa and Germany. Here's what economists Simon Cooper and Stefan Symanski wrote about the World Cup in Brazil in their 2012 book, Soccernomics:

"The Brazilian World Cup is best understood as a series of financial transfers: from women to men (who will have more fun), from Brazilian taxpayers to FIFA and the world's soccer fans, and from taxpayers to Brazilian soccer clubs [who benefit from new stadiums and marketing for soccer] and construction companies. Possibly Brazilian society deserves these transfers. Still, we have to be clear that this is what's going on: a transfer of wealth from Brazil as a whole to various interest groups inside and outside the country. This is not an economic bonanza. Brazil is sacrificing a little bit of its future to host the World Cup."