Two Saturday Surprises (EXIT POLL)

Two surprising results came out of Nevada and South Carolina Saturday

— -- Two surprising results came out of the Nevada Democratic caucuses and South Carolina Republican primary Saturday: in the former, Bernie Sanders’ showing among Hispanics; in the latter, Donald Trump’s performance among evangelicals. Each is worth a closer look.

There’s been some head-scratching about the Nevada entrance poll result; a piece in yesterday’s New York Times suggested that Sanders’ 8-point win among Hispanics was an unreliable finding, perhaps distorted by the vagaries of cluster sampling. (Clinton did well in precincts with sizable Hispanic populations, the piece pointed out, so why didn’t she win Hispanics?)

Entrance and exit polls aren’t perfect, for sure; the Times makes a fair point about their estimate of the Hispanic vote nationally in 2004 (the smaller, national exit poll produced a different result than the larger, more reliable cross-survey estimate). But extrapolating from precinct populations to caucus-goers is pretty fraught in itself. And in fact there’s a good reason for Sanders to have done well among Hispanics: They’re young.

It’s well-established that Sanders has been tearing up the house with young voters. He won 84 percent of caucus-goers under 30 in Iowa, 83 percent of under-30s in New Hampshire, 82 percent in Nevada. In a word, wow. (Context: Barack Obama, who famously whomped John McCain among young voters in 2008, managed 66 percent of their votes.)

So now let’s look at Hispanics. There were inadequate numbers of racial and ethnic minorities to analyze in Iowa and New Hampshire, but not so in Nevada. Hispanics accounted for 19 percent of voters – 213 respondents among the total sample of 1,024. That’s enough to evaluate given a probability-based sample.

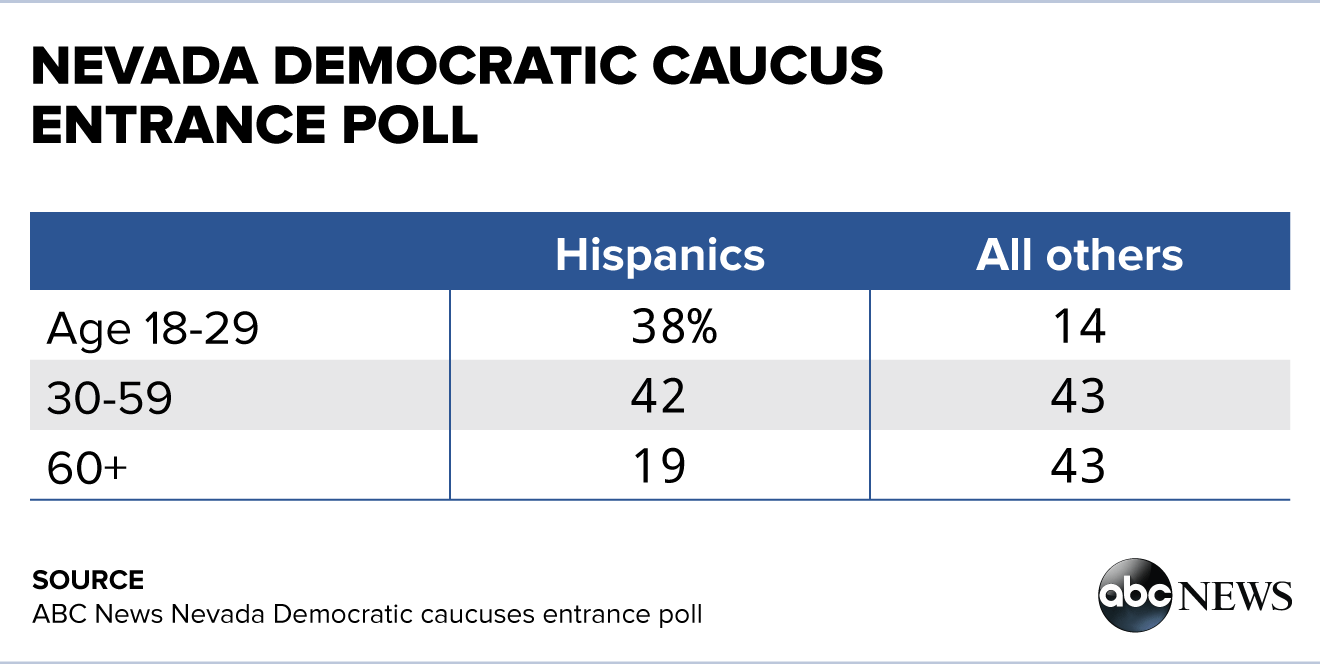

How do they look? Per the entrance poll, Hispanics participating in the Nevada caucuses were nearly three times likelier than other caucus-goers to be younger than 30, and less than half as likely to be 60 or older.

Looking at their vote choices, Hispanics younger than 45 voted 70-27 percent for Sanders over Clinton in Nevada, while non-Hispanics under 45 voted almost exactly the same, 73-24 percent. There simply were proportionately more of the former. (Further, while the sample size of Hispanics age 45+ is small, their vote was more than 2-1 for Clinton – again, similar to her result among non-Hispanics in that age group.)

Internal validity takes us only so far, but there’s also external validity for the age-by-ethnicity differences in Nevada. Per the U.S. Census Bureau, the median age of Hispanics in the state is 27.5, while the median age of non-Hispanics is 42.4. The fact that Hispanics in the state are younger than non-Hispanics would seem to support the notion that Hispanic caucus-goers were younger, too, and thus more apt to be Sanders supporters.

In all, then, there’s decent evidence that the estimate is a good one – and that Sanders did well among Hispanics not on the basis of their ethnicity, but because of their age.

The best argument for questioning whether Sanders in fact won Hispanics is that his 8-point advantage is less than the entrance poll’s margin of sampling error for this group, 10 points. Regardless, a little reality check is in order. Even if Sanders gets bragging rights for his results among Hispanics in Nevada, Hillary Clinton’s 54-point win among blacks seems substantially more significant. The vastly wider margin is one reason. There are more:

• There likely will be more blacks than Hispanics voting in the primaries to come – across the 2008 Democratic primaries for which we had exit polls, blacks accounted for 19 percent of voters, Hispanics for 12 percent. Blacks soared to 55 percent of voters in South Carolina, the next state on the Democratic calendar.

• Blacks are more widely distributed across the country, and so can make their votes felt in more states. Hispanic Democratic primary voters in 2008 were concentrated in just nine states – New Mexico, Texas, California, Arizona, Illinois, Nevada, New Jersey, Florida and New York. (Clinton, note, is a native of one of those, and a former senator from another.)

Conclusion: Clinton can let Sanders have his +8 among Hispanics – so long as she can keep her +54 among blacks.

Trump/Evangelicals

Then there’s the question of Trump’s showing among evangelicals in the South Carolina primary; they voted 33-27-22 percent, Trump-Ted Cruz-Marco Rubio. That’s surprising; Cruz beat Trump by a dozen points (and Rubio by 13) among evangelicals in Iowa, 34-22-21 percent. (The comparatively few evangelicals in New Hampshire voted 27-23 percent, Trump-Cruz, but we might think of New Hampshire evangelicals as a somewhat different breed.)

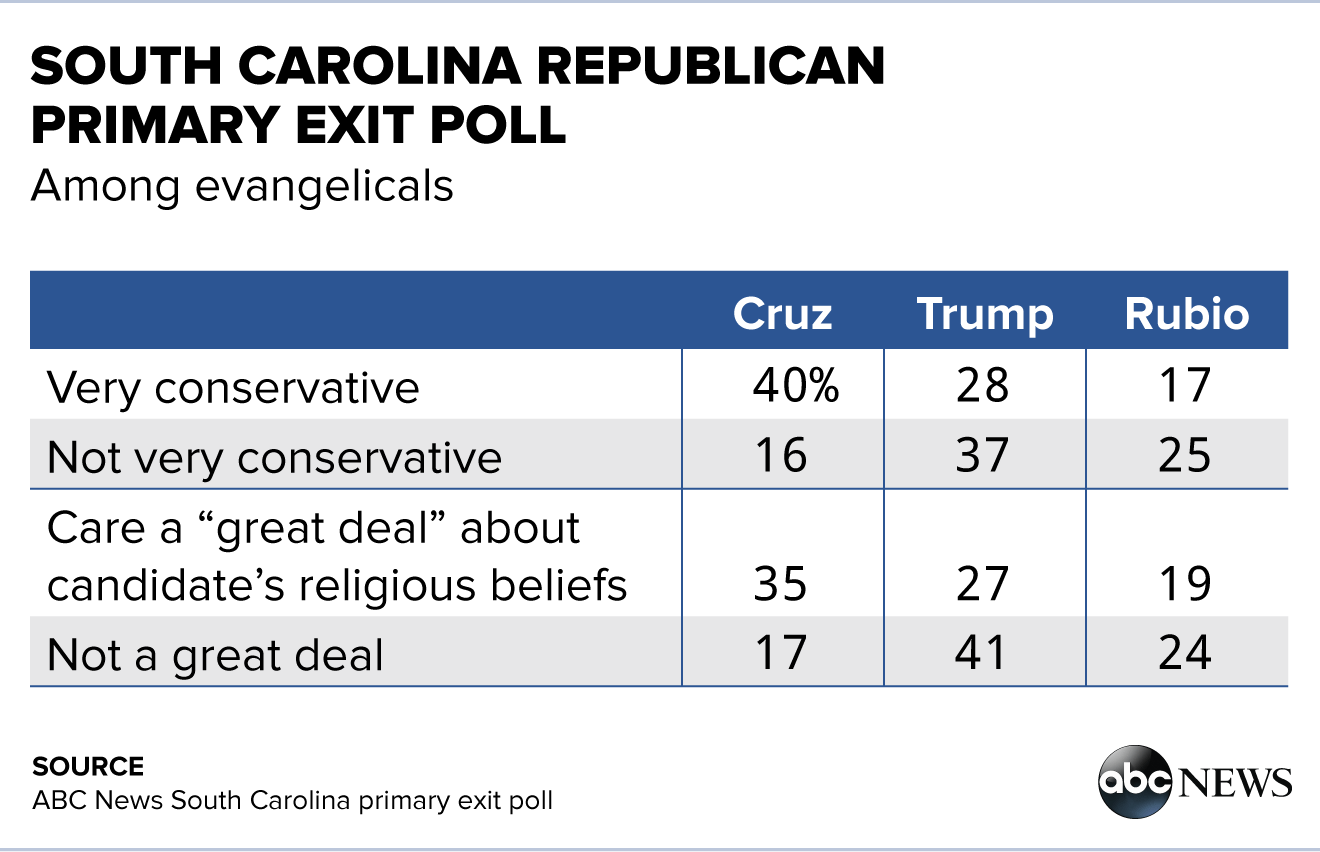

We can’t blame this one on cluster sampling and small-group estimates; evangelicals were thick on the ground in South Carolina, accounting for 72 percent of voters, up from 65 percent in 2012 to a record for the state’s GOP primaries. A group that big is going to have a range of political interests, and so we see from the exit poll. Consider:

• Fewer than half of evangelicals in South Carolina identified themselves as “very” conservative, 44 percent. They were Cruz voters; very conservative evangelicals voted 40-28-17 percent, Cruz-Trump-Rubio. But not-very-conservative evangelicals looked quite different; they voted 37-25-16 percent, Trump-Rubio-Cruz. That is, Cruz first among very conservative evangelicals. Cruz third, Trump first, among their not-as-conservative brethren. And the latter group was the larger one.

• We see a similar result looking at evangelicals who said they care a great deal that a candidate shares their religious beliefs – 54 percent of all evangelicals, they voted 35-27-19 percent, Cruz-Trump-Rubio. Among evangelicals who were less focused on a candidate who shares their religious beliefs, the vote was 41-24-17 percent, Trump-Rubio-Cruz. Same deal: Cruz first among evangelicals focused on shared religious beliefs; Cruz last, and Trump first, among all other evangelicals.

Evangelicals in Iowa were slightly more conservative than in South Carolina – 49 percent identified themselves as very conservative, vs. 44 percent, as noted, in South Carolina – and their voting pattern was very similar: Very conservative evangelicals in Iowa voted 46-20-15 percent, Cruz-Trump-Rubio. The distinction from South Carolina is that not-very-conservative evangelicals in Iowa were more dispersed in their vote preferences, 28-23-22 percent, Rubio-Trump-Cruz.

These differences shouldn't be shocking. The religious conservative Rick Santorum won 34 percent of evangelicals across all Republican primaries for which we have exit polls in 2012 - but Mitt Romney, a Mormon, was right alongside him, with 31 percent (and Newt Gingrich not far behind). The conclusion here is that when it comes to intra-party contests, evangelicals (like many groups) are not as politically cohesive as we might assume. That's a challenge for Cruz in the contests ahead – and it's good news for the man of the season so far, Donald Trump.