Jordan Spieth gracious in defeat at PGA

— -- HAVEN, Wisc. -- What's your favorite Jordan Spieth Moment of 2015?

Is it when he drilled the flagstick in the first round at Augusta National on his way to a 64? Maybe the 3-wood he smoked on the 72nd hole at Chambers Bay to set up a birdie that won the U.S. Open? How about the incredible putt on the 16th hole at St. Andrews to keep the dream of the Grand Slam alive for another 30 minutes?

Every one of those was magical, but let me tell you mine: On the 14th hole Sunday at Whistling Straits, in the final round of the PGA Championship, Spieth made a ridiculous up-and-down from behind the green -- a par save that required making a 24-foot putt. (He later called it one of the best up-and-downs of his entire life.) It came at a time when he desperately needed some late-round magic, and that putt was so pure, it was enough to give you goose bumps. He'd just cut Jason Day's lead to 3 strokes with a birdie on the previous hole, and now this unlikely par meant one final charge was still possible.

It meant nothing.

Seconds after it happened, Day rolled in a difficult birdie putt, extending the lead back to 4 strokes, and it essentially slammed the door on Spieth's comeback bid. The two men walked up the hill to the 15th tee, one of the longest walks on the whole course, Day with his head down the entire time. Spieth jogged to the tee, but when he arrived, he didn't pull out his yardage book or reach for a club. He stood, instead, and waited for Day to catch up.

"Jason," Spieth said, pausing to make sure he had Day's full attention. "That was a hell of a three, man. Seriously, hell of a three."

Day was so taken aback by the compliment, especially in the heat of competition, he broke into his biggest smile of the round. It seemed, for the first time all afternoon, as if Day was able to enjoy the moment. After so many years of bad breaks and disappointing losses, after questioning his own ability to close and trying to find inner peace through meditation, he was finally playing great golf in the final round of a major. Spieth wasn't conceding, but the comment wasn't gamesmanship either. It was acknowledgement that he was throwing everything he could at Day, and both men understood it wasn't going to phase him.

"Um, wow, thanks man," Day said. "Hell of a four by you there, too."

"Yeah, well, I needed it," Spieth said. "Such a great three by you, man. Awesome."

There are times in sports when it's fun to root for the rogue. I love creative trash talk, I love villains, and it's great theater when rivals genuinely dislike one another. And you don't necessarily have to choose. Richard Sherman barking at Michael Crabtree after the NFC Championship was funny, and a lot of the backlash to that was disgusting. I also loved watching Tiger Woods unnerve his playing partners with an icy, 1,000-yard stare. It's clear Tiger took his cues from Michael Jordan, who never met an opponent he didn't want to reduce to tears, and that produced arguably the greatest stretch of golf we're ever going to see.

But sportsmanship isn't corny either. Having an earnest appreciation for someone else's skills, especially when you're still trying to kick their butt, is genuinely great, too. This isn't war. Sports don't have to be about stepping on someone's throat, or humiliating them and taking their manhood. It can also be about the adrenaline rush you get from competing, followed by the desire to shake hands afterward.

Boo Weekley offered some excellent commentary this week about taking sports too seriously. He shot a third-round 65, then mentioned to the media he planned to spend the rest of the day fishing. He wasn't going to stress over whether it meant he was in contention.

"It's just golf," Weekley said. "They can't kill you and eat you out here. When I walk off the 18th green, it's over with. Whether it's fishing, drinking a beer or doing something, it's time to do something different."

Spieth understands that. He might be one of the most competitive athletes on the planet, and when he's trying to win a golf tournament, he is ruthless. He sharpens his focus and channels his anger better than anyone since Woods in his prime. But he also has no problem appreciating the great performances of others -- even when it comes at his own expense. That's an admirable quality, and no one should apologize for enjoying it. When the two men double-checked their cards in the scoring trailer a few minutes later, Spieth leaned over and told Day, "There was nothing I could do."

"It's a good feeling when someone like Jordan, who is playing phenomenal golf right now, says that," Day said.

When I see Spieth in defeat, I'm reminded of Jack Nicklaus putting his arm around Tom Watson or Lee Trevino when they out-dueled him in majors. Nicklaus didn't treat competition like the Cold War. Spieth's 54-strokes under par is the best all-time combined major score in one calendar year, but I will remember listening to that exchange with Day on the 15th tee a decade from now. It wasn't even an outlier.

When Zach Johnson won The Open and Spieth's Grand Slam chase ended, Spieth stuck around to watch Johnson lift the Claret Jug. When Dustin Johnson 3-putted to hand Spieth the U.S. Open, Spieth was quick to point out how heartsick he was for Johnson.

It's important to offer this caveat: I have no idea if Spieth is, deep down, a good person. It seems like he is, and I hope that he is, but no one really knows for sure. Fame could also change him in the years to come. He'll likely make mistakes, and he'll become guarded and offer less of himself to the world. If that happens, I'll still enjoy watching him play golf. He plays an exciting brand of the game, and that has little to do with his personality.

It's also dangerous to look for any real connection between athletic success and morality.

You can make a great case the opposite is true: Being selfish might be a huge part of what shapes athletic greatness. But sportsmanship, I think, is a different concept than goodness. And Spieth loves the concept of sportsmanship. When Day annihilated a drive on the 11th hole, hitting it 382 yards down the middle of the fairway, Spieth couldn't tell where it was, and when he realized it, his jaw dropped.

"When I walked up and saw where it was, I actually turned to him and said 'holy s---' Spieth said. "I yelled it over to him and said you've got to be kidding me." Day laughed and responded by flexing his bicep.

In recent years, a lot of people have rebelled against the adage that every athlete ought to "win or lose with class" because it calls to mind hectoring moralists who wielded those concepts like a cudgel as a way to settle scores, a way to play favorites and a way to disparage a younger generation of stars. It was an important cultural evolution. But the pendulum has swung pretty far in that direction. You shouldn't have to apologize if you want to root for athletes who seem like nice people.

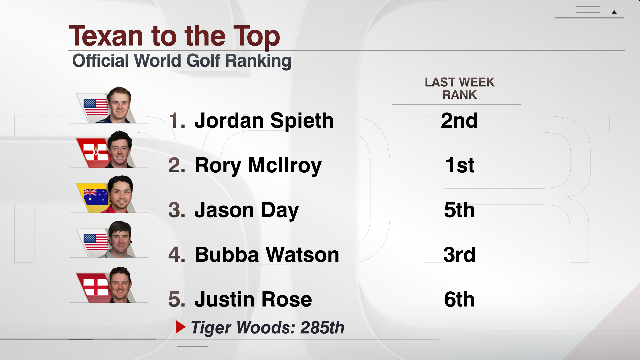

Spieth isn't a throwback. Anyone who believes that his behavior harkens back to a simpler, classier time ought to read up on what a humorless grump Ben Hogan often was. In fact, he has plenty of contemporaries who view it the same way. Finishing second to Day meant Spieth earned enough ranking points to become the No. 1 player in the world for the first time, and the man he snatched that honor from, Rory McIlroy, had no problem admitting the distinction was deserved.

"I'll be the first to congratulate him," McIlroy said. "I know the golf you have to play to get that spot, and it has been impressive this year."

When Day lagged a birdie putt close on 17, it was Spieth who first caught his eye and gave him a congratulatory thumbs up. Then on 18, as Day's eyes filled with tears, Spieth tapped in his own par putt and ceded the stage to the Australian, letting him have the last stroke of the tournament. Spieth was grinning and applauding as Day's wife, Ellie, and son, Dash, ran onto the green.