Mathew Knowles reveals he is battling breast cancer: 'We need men to speak out'

Beyoncé's father opens up on his diagnosis and the message he wants to send.

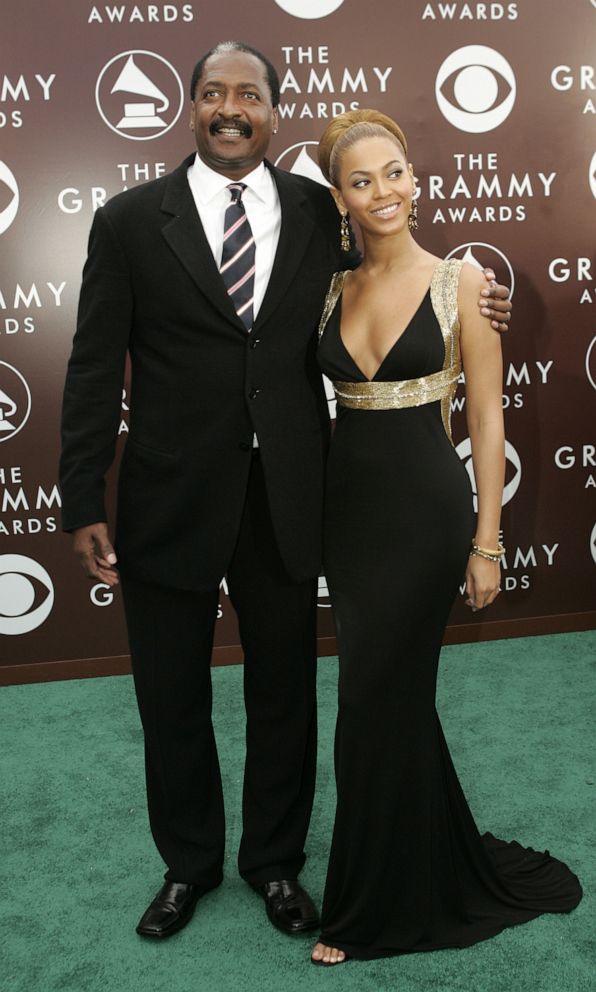

Mathew Knowles is a music executive and the father of two highly successful powerhouses in the music industry, Beyoncé Knowles-Carter and Solange Knowles. He recently announced he is battling stage IA breast cancer in an interview with "Good Morning America" co-anchor Michael Strahan. In this first-person account, Knowles shares his story on coming to terms with his diagnosis, thoughts on the stigmas attached to male breast cancer and his hopes that his account will inspire more men to speak out.

I noticed because I wear white T-shirts. I had a dot of blood on my T-shirt.

The first day I was like "Oh, OK, no big deal ... maybe it’s something that just got on my T-shirt." Second day I looked and the same thing and I was like, "Eh ... interesting."

Then on the third day I was like, "What is this? I wonder what this is."

A couple of days passed, and I didn’t have any type of discharge. Then on the fifth day, another, just a tiny drop of blood. I told my wife, I said, "Look at this," And she says, "You know, when I cleaned the sheets the other day I saw a drop of blood on it, and I didn’t pay any attention to it -- but this is kind of weird." I immediately went to my doctor.

When I had the blood on my T-shirt initially I didn’t think it was breast cancer. My mind went a lot of places. My mind went to what medication I was on, because different medications might have caused some sort of discharge ... and then I thought, just because of the risk factor, that it could be breast cancer and I would go get a mammogram.

For context, in 1980 I worked in the medical division of Xerox. I worked there for eight years, selling Xeroradiography, which was at that point the leading modality for breast cancer.

Talk about it. Speak up. Speak out. Sooner, faster, quicker about it. That’s what strength is. Weakness is when you want to keep it secret.

By being in that position, I had to learn, because I sold to radiologists, all of the modality technology terminology. Then I worked with Philips, selling MRI/CT scanners. I just want to give some context to why it got my attention, more so than others.

I knew this: Back then, it was 1 in 10 women would get breast cancer, now it’s 1 in 8 because we have more research and more data.

Also, my mother’s sister died of breast cancer, my mother’s sister’s two and only daughters died of breast cancer and my sister-in-law died in March of breast cancer with three kids – a 9-, 11- and a 15-year-old -- and my mother-in-law had breast cancer. So breast cancer has been all around me. My wife's mother has breast cancer, too.

"That is a very common thing to hear from male patients," Dr. John Kiluk, a surgical oncologist who specializes in breast cancer in The Center for Women's Oncology at Moffitt Cancer Center, told "Good Morning America." "When it comes to breast cancer we really don’t know what causes it. We are trying hard to find what causes cancer. ... I think the one thing though that we do know is that there’s a strong genetic tie with cancer."

"Female breast cancer is very common -- it happens in 1 in 8 women," Kiluk continued. "Male breast cancer is rare -- we have about 2,000 to 3,000 cases a year in the United States. ... I think anyone who presents with any kind of strong family history really do warrant to consider doing genetic testing to figure out if there is a tie that we can explain what’s going on here."

Fast forward, I go to my doctor, and I say I’d like to get a mammogram. He suggested I get a mammogram, but first he said, "Let’s get a smear."

So they got a smear of the blood, and it was nonconclusive. Then we got a mammogram and that’s when we saw that, in fact, there was breast cancer there. At least they thought. The next step is to get an ultrasound and a needle biopsy. That’s when they determined it for sure -- I had breast cancer.

The first calls I made were to my kids, and my former wife, Tina. My wife, Gena, already knew; she went with me to the exam.

It was July and I had surgery immediately, and that’s when we got back the BRCA results, a genetic test used to determine a person's chance of developing breast cancer.

I also met with Dr. Susan Domchek, director of the MacDonald Women’s Cancer Risk Evaluation Center and executive director of the Basser Center for BRCA at the University of Pennsylvania, and she shared with me this whole BRCA information that I had never heard: all men and women have a BRCA gene. The results from my BRCA test were that I had a mutation on my BRCA2.

"Men and women all have both BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes .... and men and women can have mutations in either of those genes," Dr. Domcheck told "GMA." "The risks are just a little different in men and women. Men with BRCA2 mutations have a particular increased risk of both male breast cancer and prostate cancer as well as pancreatic cancer and melanoma."

"The importance of gene testing is several fold," Kiluk said. "One is that if we do find the gene that you can give estimates on what is the probability in finding cancer in that person’s lifetime. With that information you can help guide treatments and surveillance to hopefully prevent any future issues and be very proactive. Even if the genes are negative, you still have to be very careful because who’s to say there is something we just haven’t discovered yet."

"But that being said, if we do have a gene, it really helps with counseling and screening and with the BRCA1 in particular there’s a strong tie between breast cancer and ovarian cancer and so we can be very proactive in looking out for those kinds of cancers," he added. "Usually the most common gene that we associate with male breast cancer is the BRCA2 gene and that’s probably the most common gene I come across with our male patients. One in 400 people carry a BRCA gene."

Men want to keep it hidden, a secret, we feel embarrassed – and there’s no reason for that.

Now what does having a mutation on BRCA2 mean for a man? You have a higher risk of getting breast cancer, prostate cancer, pancreatic cancer or melanoma. For women, it’s breast cancer and ovarian cancer [along with pancreatic cancer and melanoma.]

I’m still getting test results back. I got an MRI for pancreatic cancer and my pancreas and liver are fine. My dermatologist removed 2 moles -- both of which came back benign for melanoma. I got an MRI on my prostate a week ago, but we’re still waiting on the results.

I am going to get the second breast removed in January, because I want to do anything I can to reduce the risk. We use the words "cancer-free," but medically there’s no such thing as "cancer-free." There’s always a risk. My risk of a recurrence of breast cancer is less than 5%, and the removal of the other breast reduces it down to about 2%.

My kids have a 50% [chance of inheriting the BRCA gene mutation.] That’s male or female. We used to think this was only an issue for women, but this is male or female.

On using his voice to inform and inspire

I want to continue the dialogue on awareness and early detection -- male or female. The key to this is early detection.

I’m not defined by my body.

Breast cancer has been prevalent in our family. I want men and women to be aware -- if you detect the cancer early you can have a low mortality rate and live a normal life. If you find breast cancer, stage 1 or stage 2, you have a really good shot at a normal life.

But it’s the importance of going and doing it. I get frustrated that people aren’t going to get the procedure. For men and women, it’s taking the time to get a BRCA test -- just a simple blood test. You can do it in addition to any other blood tests you’re doing, or you can do it separately. It [can be as low as] $250, and it’s [often] covered by all insurance companies.

There’s no excuse for it. We’ll go get a new pair of shoes. Well, why not an important test you can go and get that could save your life? Equally important, your children's lives.

His message for those battling male breast cancer

Find a support team, and that team shouldn’t discriminate if it’s male or female. That would be number one. Talk about it. Speak up. Speak out. Sooner, faster, quicker about it. That’s what strength is.

Weakness is when you want to keep it secret.

I need men to speak out if they’ve had breast cancer. I need them to let people know they have the disease, so we can get correct numbers and better research. The occurrence in men is 1 in 1,000 only because we have no research.

Men want to keep it hidden, because we feel embarrassed -- and there’s no reason for that.

"Everyone understands female breast cancer and that we’ve come so far with advances in breast cancer. … Women go in, get their mammograms and check themselves -- everyone is hyper-vigilant," Kiluk said. "That’s why we’re having really good outcomes with females. Now on the other side, I’d say that most people don’t even realize that guys can get breast cancer. As patients, guys may push things off and say, 'Oh no, it’s nothing; it’s just a cyst or something like that.'"

"Even doctors can ignore things and say, 'Oh you’re a guy, don’t worry about it,'" he continued. "As a result, things can progress along. We don’t hear it that often with male patients that someone is a stage 1, they are usually further advanced because it’s not diagnosed early. There’s no recommendation for men to do mammograms for screening but that being said, I think it’s important that everyone be aware that ‘yes, I’m a guy but I can still get cancer and I should check myself.’ This goes for anything in the body; the patient is the best doctor. So much of cancer is early detection and giving awareness is the No. 1 piece to that puzzle."

The second thing is know your family history. This is not just for cancer, it’s for all diseases -- especially in the black community. I want the black community to know that we’re the first to die, and that’s because we don’t go to the doctor, we don’t get the detection and we don’t keep up with technologies and what the industry and the community is doing. So that’s why I’m here.

On making room for men in the breast cancer conversation

I feel gratitude that I caught it early. I have even more sense of understanding when a woman gets breast cancer and the psychological decision that it must be to have your breast removed.

We’ve got to change the process of getting an exam. Even from walking into a building that says "female breast clinic." That’s got to be rethought.

Not all the things that I went through will be the same for a woman.

How would it look? How would my wife accept it? How will other people accept it? How will I feel about myself? All of those questions -- I came up with answers.

I’m not defined by my body. My wife kinda laughed and was like, "So what? I love you." For a man, it’s easier. You know, if I open my shirt you can’t even tell. It’s an easier thing for a man.

But I do sympathize now and have empathy for a female when they have to go through that decision-making process. I think the world has gotten different, technology is different, reconstruction is available. There’s all sorts of things available today, because technology keeps changing.

In the '80s, it was xeroradiography, which is what I sold. In the '90s and 2000s, it was film. Then it became ultrasound, and now it’s really MRI technology that’s the gold standard for getting a mammogram. It’s no longer film, especially with dense breasts.

We have work to do. I shared with the University of Pennsylvania that if we’re going to try to emphasize breast cancer for both men and women we’ve got to change the process of getting an exam. Even from walking into a building that says "female breast clinic." That has to be rethought, to the point that the questions that were asked: "When was the last time you had your cycle? Have you ever had a pregnancy?" These have to change.

I want to emphasize that because that’s one of the things that keeps men from going. Just walking into a building, I know how I felt, walking into a room that said "female breast center."

It’s those things that have to change.