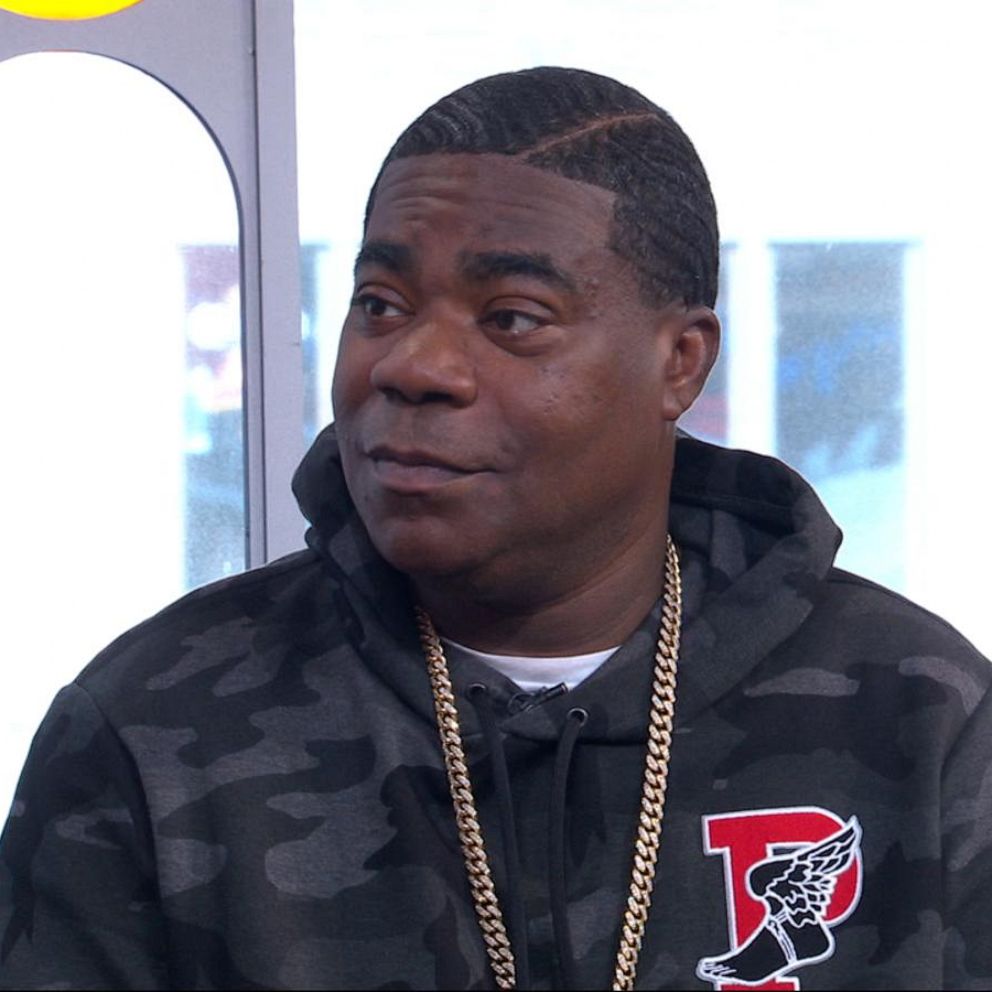

From ‘The Last O.G.’ to hosting The ESPYS, Tracy Morgan is back

Returning from a horrific accident, the comic had to learn to be funny again.

This story originally appeared on TheUndefeated.com from Kelley L. Carter, a senior entertainment writer at The Undefeated.

Tracy Morgan's sharks don't have names.

"Are you crazy?!" he asks me, jutting his head back in mock dramatic fashion at the idea of such a silly question. And then comes the isn't-it-obvious? tone familiar to anyone who has heard Morgan's deadpan delivery: "They're sharks!"

Still, he's enamored of them. Proud even. He smiles as he points out a hammerhead, a whitetip and a Japanese leopard shark. A puffer fish coexists in that same tank; he's the first fish to greet us as Morgan uses a remote control to turn the security system off and open the doors to the pool house to reveal the shark tank in the backyard of his palatial, 31,000-square-foot estate in suburban Alpine, New Jersey.

He smiles as he looks over at me. Nearby, there's a swing set and play area for Maven, his 6-year-old daughter, a barbecue grill area that only he can touch and a pool that would rival that of any five-star vacation compound.

"My babies swim in here," he says of the house his fish live in, "and my family swims out here," he says, pointing at his pool.

Morgan, who will host the 27th annual ESPYS show Wednesday on ABC, smiles again.

It's one of the last times he smiles during my time here. For much of our conversation this day, Morgan, who became famous for his ability to make people laugh, is reaching for tissues as we sit next to one another in matching leather recliners in his office, unapologetic about the tears that continually fall from his eyes.

We're only a few weeks removed from the five-year anniversary of a crash that nearly took Morgan's life. He had to learn how to walk again. He had to learn how to talk again.

He had to learn how to find, and be, funny again.

"My face was this big," he says, measuring a space big enough for three Tracy Morgan-sized heads to fit inside.

The accident was horrific. But he's been coping with trauma since he was a small child. Like many sports superstars, he understands what it takes to return from a devastating injury.

The Comeback

2019 has been Morgan's comeback year.

Yes, he's been working steadily since a triumphant return 14 months after his accident to host "Saturday Night Live," the show that made him famous.

But 2019 is where the payoff begins.

His TBS series "The Last O.G.," which he created with Jordan Peele, is some of his best work. Morgan plays Tray Baker, a recently sprung ex-con who is surprised to see how much Brooklyn, New York, has changed during his 15-year stint in prison, with chain coffee shops, yoga studios and white people inhabiting the old haunts where Baker once worked as a petty drug dealer.

The series launched as the network's biggest original TV debut last year, came back for a successful second season and was recently renewed for a third. The funny wasn't a surprise — this is Tracy Morgan, after all — but the show's depth was revelatory.

"A lot of times as a writer you're scared of playing with the tone too much because people, admittedly, tune in to a show because they want to laugh or they tune in to a show because they want to see dragons. Very few of us ever think consciously, 'Oh, I'm going to tune in to that show because I want to laugh and cry,' " says comedian and actor Diallo Riddle, who wrote on season one of "The Last O.G." "But I think that Tracy had such a good relationship with his audience and such a good relationship with the truth. Even old white people in rural communities can watch that show and watch black men in Brooklyn and be like, 'I love Tracy Morgan!'"

"The ESPYS is a beast of an undertaking. It's not easy physically or mentally. And the fact that he's hosting it, given where he was, is incredible."

The good news doesn't stop there. Later this year — Morgan beams every time he mentions this — he'll begin filming his yet-to-be-announced role in the highly anticipated "Coming to America" sequel that is set to hit theaters sometime next year. Eddie Murphy is an idol, and now he's also a friend.

And this week, of course, the 50-year-old Morgan will host The ESPYS, perhaps his biggest audience since the "Saturday Night Live" gig in October 2015.

"I still remember the time I saw Tracy after the accident and you just go, 'I'm so happy he's alive.' That's all you could say," Riddle says. "I'm so happy he's alive because he kept grinding, and then to go into a third season of the show and to be hosting The ESPYS? … The ESPYS is a beast of an undertaking. It's not easy physically or mentally. And the fact that he's hosting it, given where he was, is incredible."

Finding funny through pain

Back inside his home, Morgan is wiping away a fresh set of tears.

I ask if his ability to be emotionally open is a result of his accident or if this is who he was before June 7, 2014. We don't generally give black men license to feel like this — not without it being some sort of indictment of their masculinity.

His life has been painful, far more than one person should have to deal with, really. And Morgan allows himself to be, well, human.

"My dad survived Vietnam … he came home a junkie. He didn't go there that way, [but he] came home that way. That was his terror, seeing babies dying in villages, and he expressed those to me," Morgan says. "I didn't understand it because I was a kid in [his] prime in high school, playing football, but I didn't know what his struggles. … He had demons. You go to war, nobody wins."

Certainly not Jimmy Morgan Sr., who died of AIDS when Tracy was 19. Morgan also talks about how much he looked up to his Uncle Alvin, the cool uncle who played college football and who died of the same syndrome.

That kind of trauma can be crippling. Somehow, Morgan discovered comedy.

"You find it in that pain," he says softly. "Without no struggle there's no progress. People don't know. 'How did he get that funny?!' My father and my mother breaking up when I was 6. My oldest brother being born with cerebral palsy. … Him having 10 operations by the time I'm 5. My mom's by herself, struggling to help my brother with them Forrest Gump braces on, him screaming, she trying to teach him … I seen all of that."

Morgan pauses.

"You know why I became famous?" he asks quietly. "Because the kids of the playground could be mean. When they be mean, you go get your big brother, your big brother got your back. … I couldn't do that. I go get my brother, he come, hey, he crippled. They start laughing. So I had to learn how to be funny to keep the bullies off my a–. All of my life, turned into business."

Then, as if tossing it over in his head for a bit, he chases all of that heft with some lightness: "And plus, I learned in high school, when you funny, you get the girls. You might not score, but they be all, 'Where Tracy's stupid a– at?" he recalls. "They want you around, you make them laugh! My biggest audience is female. Same motivation. I'm married now, but I still want to make the girls laugh. Y'all got the world on your shoulders. At the end of the f—ing day, if you can make her forget about all that s— for an hour, you the man."

"Great comedians — which Tracy is one of the great comedians — their comedy comes from pain," says director David E. Talbert. "And the great ones allow themselves to access that, and then they share that."

Morgan's first taste of fame came in 1993 via HBO's "Def Comedy Jam," which was hosted by Martin Lawrence. Back then, it was a must-watch series, introducing and amplifying many now-famous black comics such as Chris Tucker and Bernie Mac.

His childhood best friend Alan always told him how funny he was and that he should really make a go at pursuing comedy. Morgan, who was born in the Bronx and reared largely in Brooklyn, took workshops and eventually was working the local comedy club circuit. Comedy was his love, but he still had one foot in the hustle game.

"I was selling crack [when] my friend Alan got murdered, my best friend," Morgan shares. Losing Alan made him focus.

"I come home, my youngest son is 2 years old. … Told him, 'I'm gonna do comedy. …' By all means, [my first wife, Sabina] could've said, 'No you ain't m—–f—-, we got three kids. What you going to do is go get a f—ing job.' She never did that. She said, 'Pull the trigger, Tracy.'

"Four months later, I was on "Def [Comedy] Jam."

And then, another painful memory: "She passed away three years ago. Cancer."

Moving forward with forgiveness

Morgan was almost gone too.

On June 7, 2014, a Walmart truck driver who had been awake for more than 28 hours was going 20 mph over the 45 mph speed limit in a work zone on the New Jersey Turnpike. He crashed into a limousine bus carrying Morgan and a small group of friends and colleagues. Morgan's friend James McNair died, and Harris Stanton and Ardie Fuqua were hospitalized. Morgan himself was listed in critical condition and was comatose for two weeks.

The driver, Kevin Roper, was indicted on charges of manslaughter, vehicular homicide and aggravated assault. He later accepted a plea deal that dismissed the charges in exchange for entering a pretrial intervention program. Walmart settled for an undisclosed amount of money.

Morgan's life changed that day. He came out on the other side appreciative. Attentive. Spiritual, yet spirited.

"When bad things happen to you, that's when you grow. It was painful at the time," he said. "But now you look back on it and you go, 'Wow.' So this story is not just for me. It'll be for the young people who want to achieve anything in their lives. You can't give up. I got hit by a truck!"

But before he could do the work physically, Morgan's road to recovery had to start with forgiveness.

"You have to learn to forgive yourself before you can forgive anybody. OK, you had a setback on the field. But a setback ain't nothing but a setup. Because when you come back better, you going to do something that ain't been done," Morgan says. "Don't you ever let no doctor, nobody, tell you you can't. They said no, I broke every bone in my face. On this side of my skull you could see my brain. … I was scared. I didn't know if I was ever going to walk. That's when I had to put the work in. …"

Morgan begins to cry again.

"Ugh. Damn. Excuse me."

I tell him to take his time. Soon, he begins to tell a story of sitting in his wheelchair and watching his infant daughter scoot around in her walker.

"I don't want her looking at me like this; she ain't understand what's going on. I'm working, I'm working hard, because I want to walk again, I want to play with my daughter, I want to chase my daughter. That was my motivation. I wanted to chase my daughter. I didn't care about show business. I wanted to chase my daughter," he says, wiping away fresh tears. "And I worked so hard for a year just to get back on my feet. And I don't care what athlete you are, you better pick a motivation, something near and dear to you. Something that you would give the world for. And you better go for it, don't let it be over. I put the work in for a year, and then the triumph, like we was talking about. I saw my daughter — she was 14 months — and I seen her take her first steps. It made me get out my wheelchair."

"I saw my daughter — she was 14 months — and I seen her take her first steps. It made me get out my wheelchair."

I ask him to clarify: Seeing his daughter take her first steps motivated him to attempt to take his own first steps?

He nods.

"She took her first steps and I got up, and my wife started screaming. She said I was going to hurt myself because my femur was crushed. And I was like, 'F— that,' and I stood up and I took a step to my daughter. I took a step with my daughter," he says. "That was four months after I got hit. The rest of the year, I just started working. It wasn't just physical, it was cognitive — I didn't even know my name. I had to learn how to talk again."

Drying up the last tears with a new piece of tissue, he says, "It was a bad accident."

Life imitates art

This is who Morgan has always been.

In 2008 he co-starred alongside Ice Cube in "First Sunday," a comedy written and directed by Talbert, who was a top-grossing playwright before he directed Morgan in what was his directorial debut.

In that film, Morgan played LeeJohn Jackson, best friend to Cube's Durell Washington. Together they were portraying petty thieves who concoct a rather desperate scheme to steal $17,000 from a neighborhood church to pay off a debt for Washington's ex-girlfriend — to not do so would mean that she and their son would relocate to a different state.

"This story is not just for me. It'll be for the young people who want to achieve anything in their lives. You can't give up. I got hit by a truck!"

After Morgan auditioned for the role, he and Talbert went out for lunch.

"He started telling me about his relationship with his mother, which is a complicated relationship," Talbert recalls. "I knew that if I could access that, then he could really dig into the character.

"And I remember when he was about to do his big scene with Loretta Devine. And he says, 'Today I'm going to cry because real actors cry! Richard Pryor cried!' That's all he was screaming all day! The scene singing 'Happy Birthday' with Loretta Devine, he was just telling everybody, 'I'm going to cry! Real actors cry!' "

Talbert gave Morgan some advice before they dug into the scene: "I said, 'Tracy, the thing about emotion is you have to try not to cry, but it moves you so much that you can't help but to cry.' And I said, 'So I want you to try as hard as you can not to cry. And as she's singing to you, I want you to think about all those birthdays that were missed.' "

That scene is one of Morgan's favorites. By the time Devine gets to the last few notes of the song, she pulls Morgan in close for an embrace. The camera zooms in on his face, a mixture of bewilderment and sadness. Tears are streaming down the sides of his nose.

It wasn't just good acting. It was real life. When Morgan was 13, he left his mother's home to live with his dad in the Bronx. He and his mother went years without speaking.

"Loretta Devine started singing. And Tracy, I saw him. [He] wasn't playing the character anymore. He was the little boy thinking about his own relationship with his mother. And slowly as Loretta started to sing, he was welling up and just the most genuine, authentic tear fell. I yelled, 'Cut!' I only had to do one take of that scene," Talbert says. "It was beautiful. It was perfect. I only did one take, and he said, 'D, excuse me for a moment.' And he went to the back, and about 15 minutes later he came out and I said, 'You OK?' He said, 'I just called my mother and I told her she missed out on a real actor.' "

Since the accident, Morgan and his mother have reconciled.

'I'm here.'

As we're wrapping up, I remind Morgan of a joke I once heard his friend Chris Rock tell in a stand-up routine. Rock observed that he was the only black man in his tony neighborhood and shared all he had to accomplish to afford to live on the street. One of his neighbors is a dentist, Rock said, before landing the punchline: "Know what I had to do to afford this house? Host the Oscars!"

Morgan breaks into the hardest laugh I've heard from him this day. He has a similar story.

"Just last week I had some rich white man jogging in front of my gate. So I'm coming out my gate, and he's looking at my house. And he's looking at me …"

"So what do you do?" the jogger asked him.

"And I said, 'About what?!' "

Morgan and I both break out laughing.

"I had to justify why the f— I live here … but you know I start f—ing with him," Morgan says.

"You know the McDonald's box the french fries come in?"

"Yeah."

"I make those. You know the straw you drink the Coke [out of]? I make those."

Morgan laughs at his own story.

"And he started laughing. … In your mind, you got to justify why I'm here."

Tracy Morgan is here — and hosting The ESPYS.

"That's going to be fun. Because everybody knows that Tracy Morgan thinks outside the f—ing box. … Buckle up, kids. It's about to get wild and woolly."

Kelley L. Carter is a senior entertainment writer at The Undefeated. She can act out every episode of the U.S version of "The Office," she can and will sing the Michigan State University fight song on command and she is very much immune to Hollywood hotness.