A Brief History of the National Park Service: A Century of Conservation

How a nation raised on conquering wilderness came to embrace conservation.

— -- For much of American History, wilderness was viewed as an evil wasteland that had to be conquered. Land left untouched by man was described as “deserted,” “savage,” and “barren” -- in short, a waste of divine gifts.

But by the end of the 19th century, backlash against a rapidly industrializing society ushered in a new fascination with the natural world.

Writers like John Muir and Henry David Thoreau, as well as painters such as George Catlin and Thomas Cole were busy redefining wilderness as “the preservation of the world” where “nature may heal and give strength to body and soul alike.”

In 1832, Catlin was travelling the Great Plains to document disappearing Native American tribes when he penned the words credited for creating the concept of a national park. “By some great protecting policy of government,” Catlin argued for, “a magnificent park ... a nation’s park, containing man and beast, in all the wild and freshness of their nature’s beauty!”

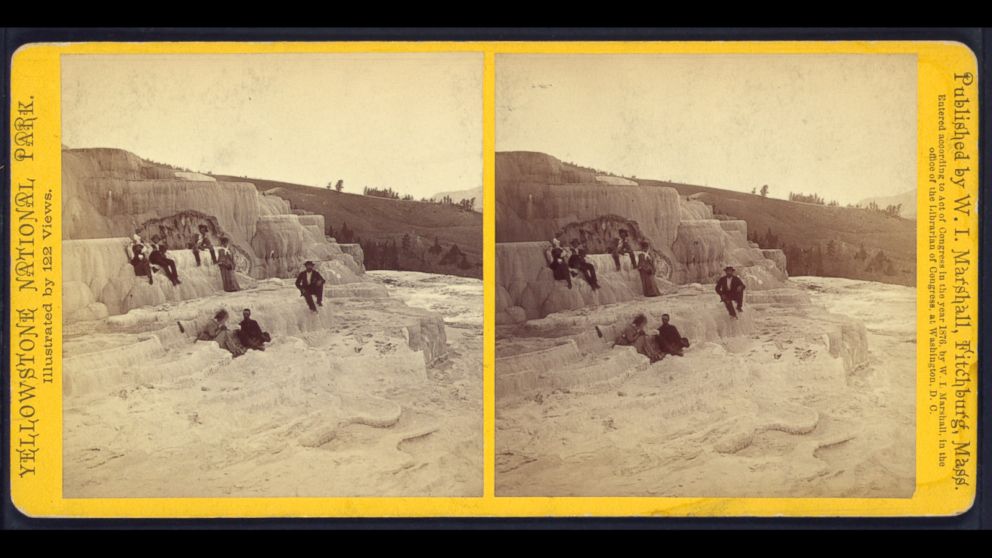

A few decades later, in 1872, Catlin’s dream came true when a natural wonderland spanning Wyoming, Montana and Idaho became the world’s first official national park. They called it Yellowstone.

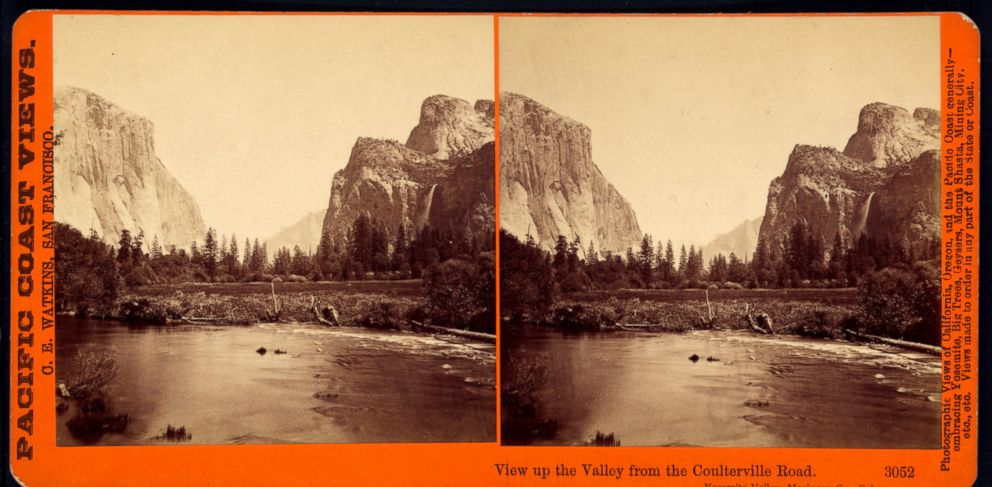

Further west, in California’s Yosemite Valley, a controversy was brewing. While the area had been deeded to the state in 1864, with portions belonging to the federal government, Muir believed the state-managed areas were being exploited and lobbied Congress for it to become a national park under full federal control.

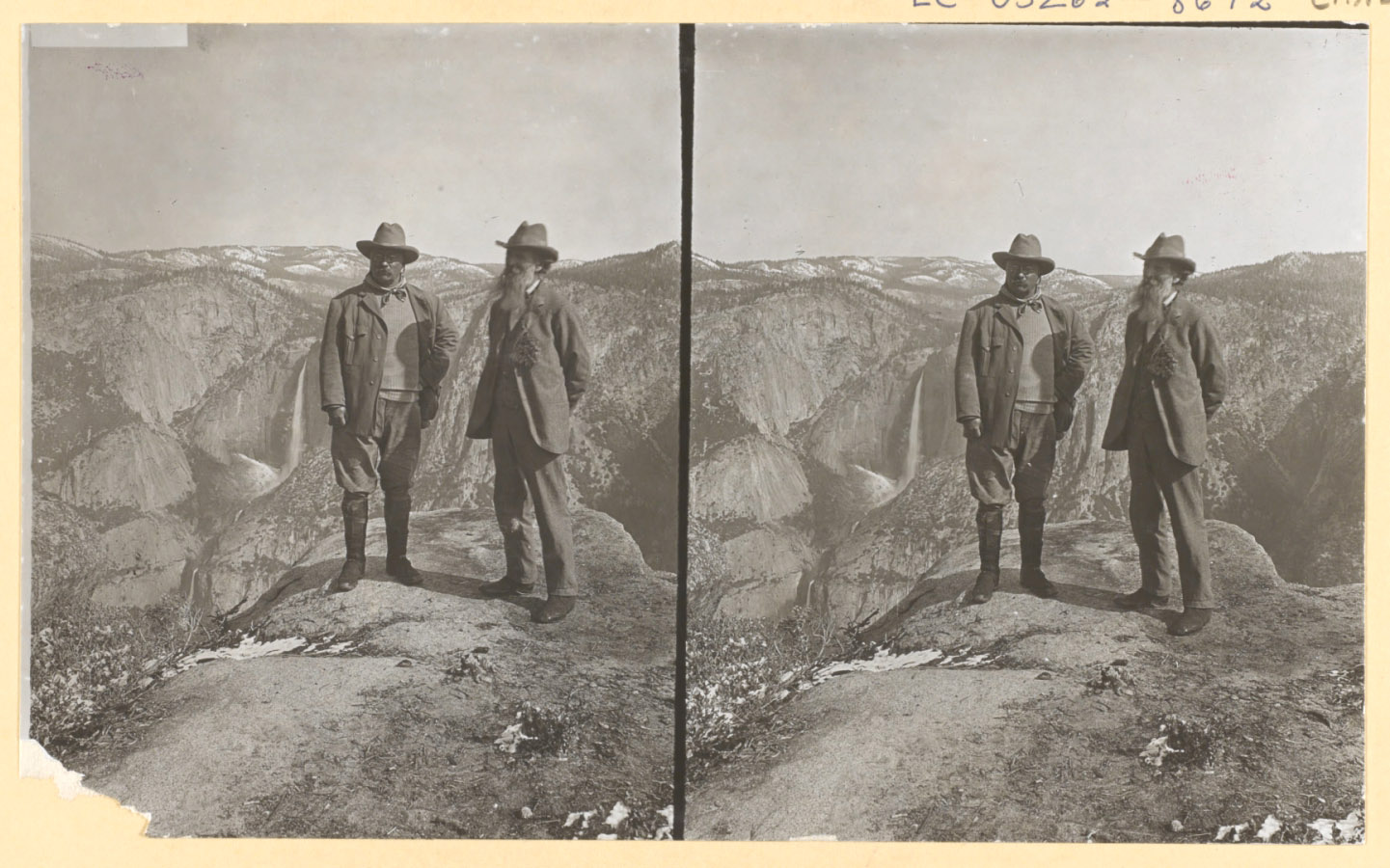

In 1903, Muir convinced President Theodore Roosevelt to join him on a camping trip in Yosemite, and three years later the park was under full federal control.

That same year, Muir tried to save the Hetch Hetchy valley from a proposed dam that would flood the valley to provide water and power to the city of San Francisco. The resulting controversy pitted two schools of American environmentalism against each other: preservationists v. conservationists.

Preservationists, led by Muir, believed in maintaining the present condition of natural areas, while conservationists, led by forester George Pinchot, believed in the sustainable management of natural resources.

Muir and the preservationists were against the flooding of Hetch Hetchy while Pinchot and the conservationists were for it.

When congress decided to go ahead with the proposed dam, flooding the valley Muir called “the holiest temple ever consecrated by the hearts of man,” preservationists were dealt a death blow and conservationism emerged as the country’s prevailing environmental movement.

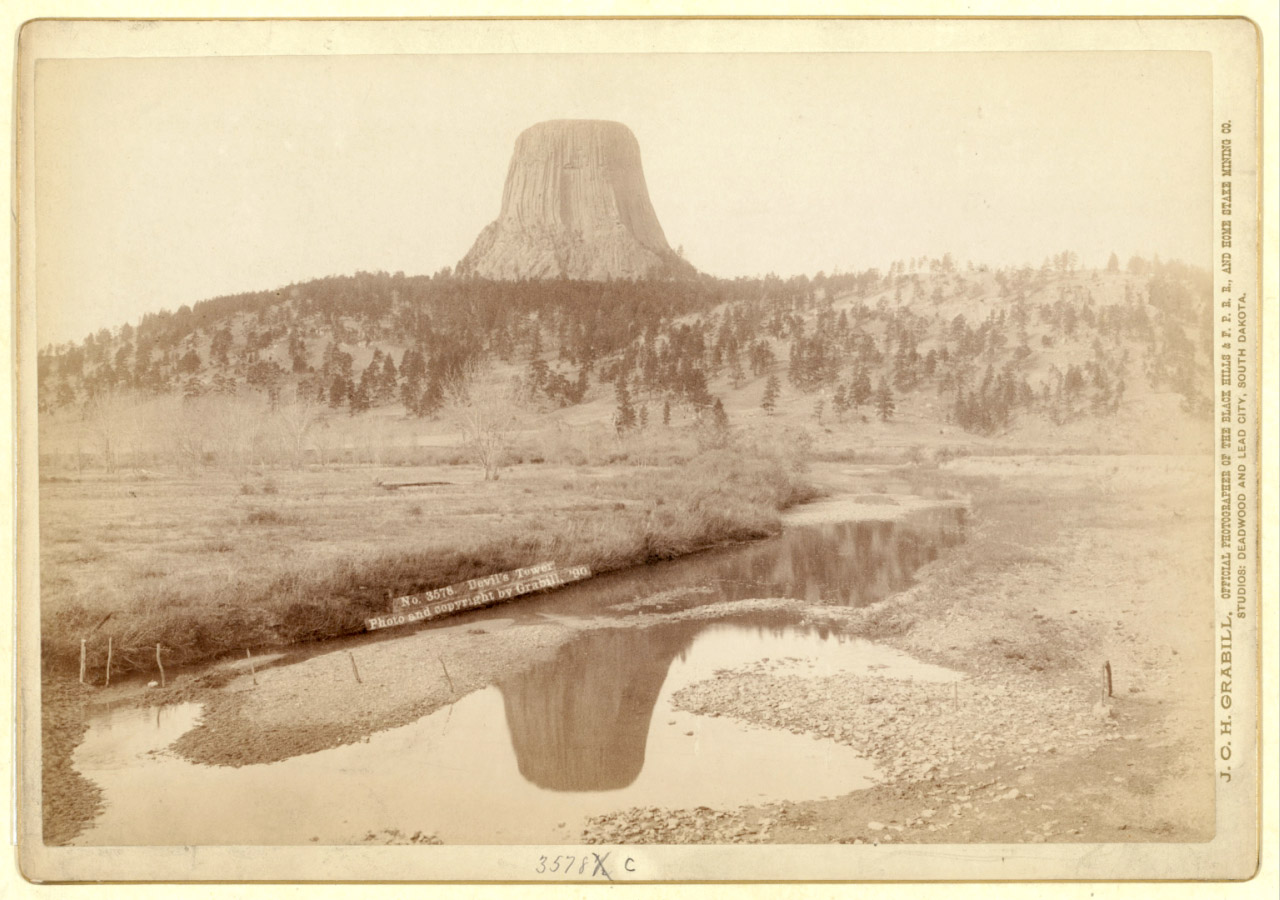

By 1906, Congress helped expand the parks system by passing the Antiquities Act, which granted the president the authority to set aside historic landmarks that already existed on public lands.

Roosevelt took swift action, proclaiming Wyoming’s Devil’s Tower as the first national monument that year and establishing a tradition that would continue to today.

For more than 40 years, the nation’s parks were supervised at different times by the Departments of War, Agriculture and the Interior. But President Woodrow Wilson sought to clear the bureaucratic mess and created the National Park Service on August 25, 1916. By 1933, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt further streamlined the agency with Executive Order 6166, which consolidated all the national parks, monuments, memorials and cemeteries into a single national park system.