As income inequality soars, languishing labor unions make a return

In the wake of high-profile strikes, experts say unions could see a revival.

After decades of declining membership and seemingly sidelined authority, a series of national strikes has put unions back in the spotlight. And as economic inequality has become a hot-button issue for workers and candidates on the 2020 campaign trail, some experts have said a surge of emboldened organized labor movements could be on the horizon.

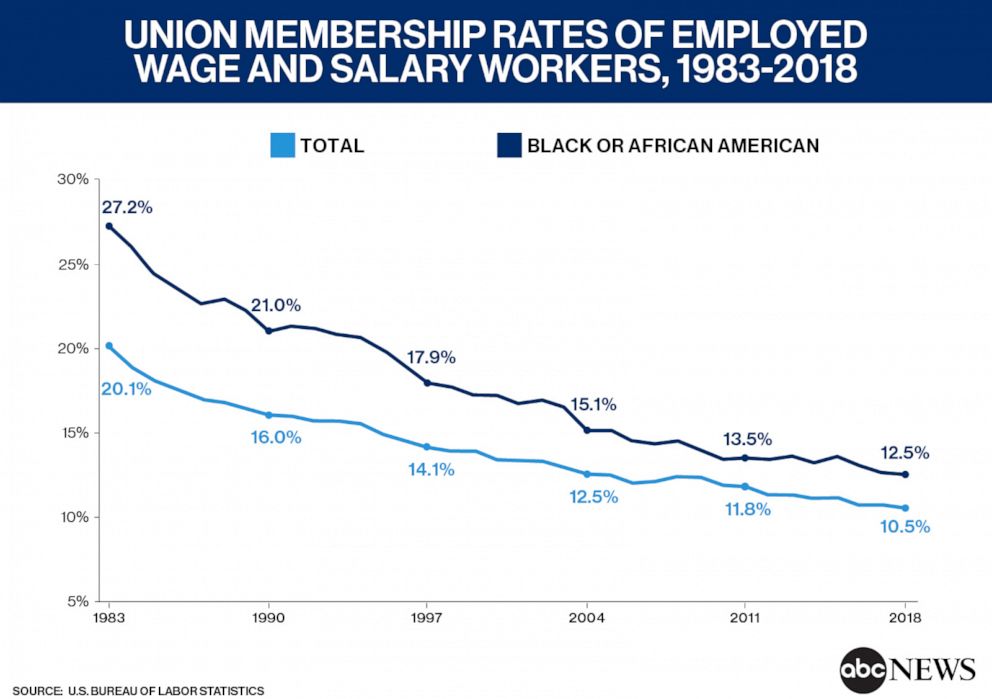

Once considered by many to be essential, union membership is a fraction of what it once was: Approximately 10% of U.S. workers were part of a union in 2018, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. In 1983, the first year the department collected data, the number was more than twice that -- over 20%.

"We've had massive union decline -- back in the '40s, over 30% of workers were unionized in this country," Sylvia Allegretto, a labor economist and the co-chair of the University of California, Berkeley's Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics, told ABC News.

While union members account for only a fraction of the workforce, recent actions have forced them back in the public eye.

Last month, the United Auto Workers completed the longest auto industry strike in 50 years at General Motors, and ended it with $11,000 bonuses, higher wages and clearer paths to full-time status for temporary workers.

Similarly, last month, the Chicago Teachers' Union organized a 15-day strike that ended with pay raises and a pledge to reduce class sizes.

Presidential candidates, including Sen. Bernie Sanders, Sen. Elizabeth Warren and former Vice President Joe Biden, joined strikers on the picket lines, and a slew of politicians expressed support on social media.

In the wake of these two highly publicized strikes, the Association of Flight Attendants announced this month that it's organizing an effort to unionize Delta flight attendants for the first time.

"Union organizers I've talked to have said that there is a dramatic pick-up in the number of people interested in organizing and trying to gain collective bargaining," Larry Mishel, a labor expert and distinguished fellow at the Economic Policy Institute, told ABC News.

"Working people have taken it on the chin for many decades. They've been not able to get the help of government to be on their sides, the employers are suppressing their wages," he added. "And now they are being shown that some collective action can actually work."

"If people see that they can solve their problems through collective bargaining -- and even striking if they have to -- then they will do that," Mishel said. "And I think that's what we're seeing."

'The economy is booming ... but my paycheck has gone nowhere'

The ratio between the highest- and lowest-paid Walmart employee is more than 1,000-to-1. Many other U.S. corporations have pay ratios exceeding 500 to 1. Teachers and other full-time workers often cannot afford housing in major U.S. cities despite strong economic indicators.

Unions may be seeing a revival due to "the rise of economic inequality in the country," according to Joseph Kane, a senior research associate and associate fellow at the Brookings Institute's Metropolitan Policy Program.

The top 1% of the U.S. holds more wealth than the entire middle class, according to the Brookings Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank.

It wasn't always this way: Prior to 2010, the middle class owned more wealth than the top 1%. Since the mid-90's, however, the share of wealth held by the top 1% has steadily increased, while the share held by the middle class has steadily declined, according to Brookings.

"Not all people are sharing in the economic gains that we are seeing," Kane said. "That's led to some very real frustrations and curiosity, I think, of, 'Well, what can unions do about this?'"

While many unions probably would agree that strikes are a "last-resort" option, Kane said these high-profile strikes are "magnifying some of these broader interests in what unions and organized labor can do to help people."

Allegretto added that some of the recent teacher strikes happened at a "time when economic growth was happening for quite a while" in the decade following the 2008 recession, and "most of the states had already fulfilled their budget shortfall, but what a lot of them didn't do was replace the money that they took away from the public education."

"One part of the story is why the teachers said enough is enough," she added. "In Oklahoma, those teachers did not have a raise in over two decades. I think that's kind of what we're seeing now.

"I think workers are really saying, 'What are we supposed to do here? The economy is booming, the economic pie has grown considerably, but my paycheck has gone nowhere.'"

It certainly helps workers who might face discrimination in the work place get a better deal.

While union membership has declined across the board, it has dropped the slowest among black workers, who remained more likely to be union members than any other race in 2018, according to BLS data.

"We know that unions tend to raise wages for those who have the least wages, so they tend to disproportionately help minorities," Mishel said of the statistics. "So Hispanics and blacks are very favorable in union organizing drives, and we see women growing more than among men in various sectors."

Allegretto added that because unions bargain collectively, everybody "under the collective bargaining agreement is getting the same deal, so it certainly helps workers who might face discrimination in the work place get a better deal."

So why the massive decline in union membership?

Employer resistance, especially in the private sector, and changing labor laws have a "big role to play" in the decline of union membership, Kane said.

Mishel added, "There's an easy tale to tell that's actually wrong: That somehow the union decline is all due to automation and globalization."

"But," he added, "union density has fallen even in construction, communication, supermarkets, just across the board."

He added that "employer opposition has been severe" and organized labor "imploded" in the late '70s and '80s.

"It's primarily declining in the private sector, and, really, the main one of the leading reasons is that employers' actions in the 1970s and some changes in the law really made it extraordinarily difficult for workers to become organized," Mishel said. "If you get fired for trying to get a union where you work, it's illegal to get fired for that, but what happens? Well, it takes five or seven years, and maybe you will get your job back."

Allegretto said that it has become nearly "impossible to form new unions in the United States."

The erosion of unions leads to not only lower wages and benefits for workers but "hurts our democracy," according to Mishel. "It doesn't allow our workers to be represented in the political process the way they used to be."

Despite the difficulties in organizing, Allegretto said that especially at a time like now, many workers are looking to stronger labor unions redress glaring economic imbalances.

"We do know that the stagnating wages, that inequality has grown so much," Allegretto said. "A very large share of that inequality has to do with the decline of unions and the decline of union power."