US-Canada trade deal may mean higher car prices

The new trade deal with Canada and Mexico may be bad for consumers.

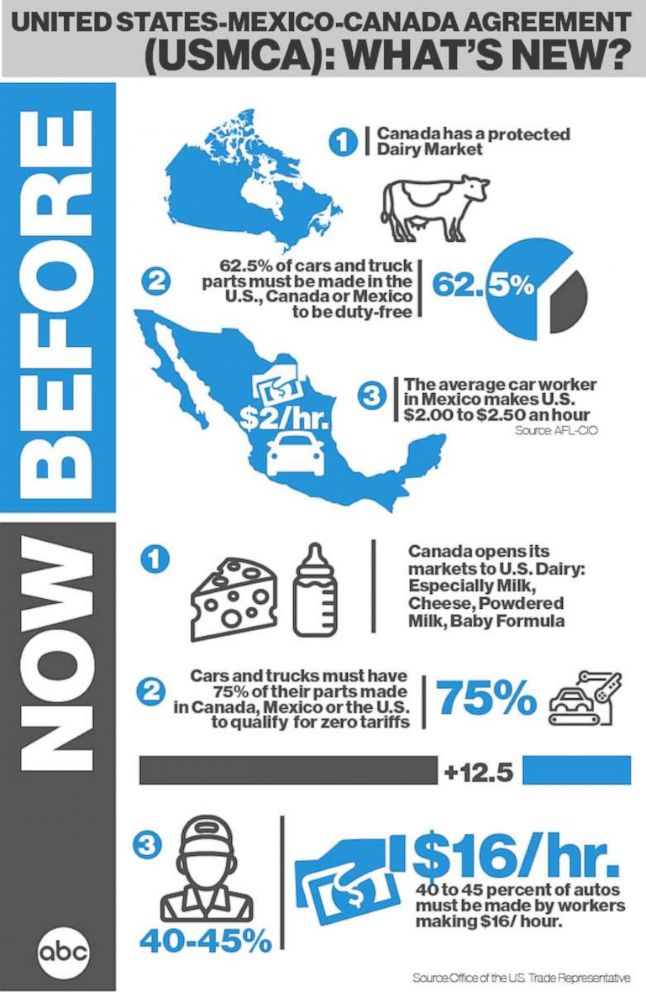

The U.S. and Canada squeezed out a last-minute deal to revamp the North American Free Trade Agreement with a pact expected to affect prices on cars and dairy products across North America and allowing President Trump to deliver on one of his go-to campaign promises.

The new deal was greeted warily by unions and market watchers. Americans avoided a 25 percent tariff on Canadian-made cars, but may still see an increase in prices because of new manufacturing and labor agreements.

The U.S. and Mexico came to a deal at the end of August that will be part of the overarching agreement that includes Canada. The so-called U.S.-Mexico-Canada Agreement, or USMCA, still needs to be approved by Congress and the legislatures of Canada and Mexico before it's implemented.

"It's too soon to declare victory or defeat -- let's just slow our roll before deciding," Celeste Drake, a trade specialist at the AFL-CIO, told ABC News, noting that the latest draft of the deal she saw included text such as "not available or in draft form or missing."

"There could be a lot of changes," she added. "We don't know what's in there. There are some things to like, some things not to like and a lot of unknowns."

For example, the new agreement would require 40 to 45 percent of auto components be made by workers earning the equivalent of $16 per hour, but it's unclear whether $16 would be the average or the minimum earned, or how such a measure would be enforced, Drake said.

In addition, 75 percent of auto parts now need to come from one of the three countries to stay duty-free, according to the agreement. Mexico also would allow autoworkers to unionize.

"If anyone thinks this is a good deal, then you've had the wool pulled over your eyes," Edmunds analyst Ivan Drury said. "What it spells out for consumers is that they'll be paying more. It's the opposite of what NAFTA stood for."

Under the USMCA, the limitation on having auto parts sourced from North America means higher prices that will be passed on to consumers, Drury said.

"If there's something you want," Drury continued, "something on your vehicle that's made in Japan or China, as we go toward electrification and auto-driving, all of these things are new parts -- how do you come down on parts? You go to the cheapest place possible unless you can get it so much cheaper from the foreign place that you can eat up the cost of the tariffs."

United Auto Workers President Gary Jones issued a statement that read, in part:

"New protections for working families and the closing of some loopholes for global companies seeking to ship jobs overseas are a step in the right direction but there is more work to do. We need to be assured that Mexico is going to fix weak labor laws and enforce new worker protections. We need to review and resolve the details of the agreement when they are available."

It's unclear whether the new agreement includes not implementing the 25 percent steel tariffs Trump had threatened. At a veering press conference on Monday, President Donald Trump said the tariffs might stay in place.

In Canada, farmers protested the increase in quotas on U.S. dairy products including milk, yogurt, milk powder and formula. Chicken, eggs, turkeys and American wheat are also headed north in greater volumes.

Still, at least one trade expert said the deal was far from perfect, but needed to be done.

"I think it's the best deal they could have made," said Mark Warner, an international trade lawyer. "They made more concessions for dairy, but it's better than a 25 percent tariff on cars."