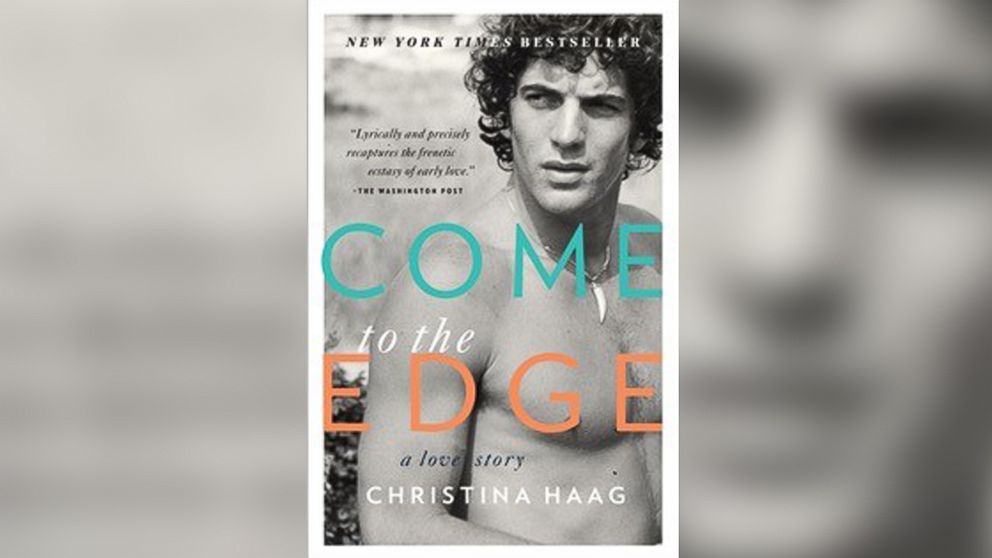

Book excerpt: Christina Haag's 'Come To The Edge'

Christina Haag is an award-winning actress and a New York Times bestselling author. She met John Kennedy Jr. in New York City when they were both 15. Her memoir, Come to the Edge, chronicles their long friendship and five-year love affair.

This is an excerpt from the book "Come to the Edge" by Christina Haag. Copyright © 2011 by Christina Haag. Published by arrangement with Spiegel & Grau, an imprint of Random House, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All Rights Reserved.

We had been together more than a year, and there were things I had learned. He was chivalric and competitive, puritan and sensual. He wore Vetiver and Eau Sauvage, and when he didn’t, his skin was like warm sun. He loved to cook but burned his food, and he slept with the windows open. I wore his sweaters, he ate off my plate, and we spent most nights at his apartment on Ninety-first Street. And if he was in a mood and I wanted something, a small thing -- a light turned on, a fan turned off -- I found that if I said the opposite, it worked like a charm. When I smiled and told him this, it made no difference. Like a reflex, he was helpless to it. He had a theory, he said, that what he called his occasional contrariness was due to being “bossed by so many women” when he was young.

There were things he would say like mantras. They might have been passed along by someone wiser, someone who knew, his uncle, or his mother maybe. He ’d say them to remind himself of human nature and the way of the world; that struggle wasn’t always the best path, but sometimes it was; and that whatever Fortune brought, it wasn’t because he thought himself superior. He had faults, like anyone, but never arrogance, never meanness, never snobbery. What he aimed for, and succeeded some days in attaining, was the remarkable equipoise of humility and confidence that is grace.

My apartment, eight blocks from John’s, had a terrace that jutted over the parlor floor below, and whether he remembered his key or not, John preferred to enter through my window. He’d give a whistle—soft, two-toned, and flirty -- and with a foot on the stone planter and his hand on the iron rail, he ’d hoist himself up the side of the brownstone. I liked it, and the neighbors got used to his Romeo act, but one night when we were in bed, we heard a voice through a bullhorn.

“This is NYPD. Come to the window.”

We burst out laughing. Then a spotlight froze the room.

“You go to the window,” he hissed.

“No, you!”

“Come on . . . the papers.”

I did what he asked and lifted the sash. Everything’s fine, I explained. Just my boyfriend crawling through the window. Below, three officers stood in front of a double-parked squad car, the cherry lights whirling like mad. One of them aimed a bright beam on my face.

“Ma’am, I’m sorry. We need to confirm you’re all right.”

“Really, Officer, I’m fine.

“Ma’am, whoever’s in there needs to come to the window at once, or we will enter the apartment.”

John stepped beside me, and they turned the light on him. He spoke with an easy, self-effacing charm, the same way he did with reporters and people he didn’t know well. He didn’t press the point or pull rank; he simply wondered if this might stay off the record. Even two flights down, they recognized him -- not right away, but when the officer in charge began to apologize at length without blinking, it was apparent. Before they got back in the squad car, the junior guy, slow on the uptake, suddenly began shaking his head. “Sir, I think . . . Was that JFK Jr.?”

I closed the window and pulled the lock shut. John was back in bed, hands behind his head and ankles crossed. He looked pleased. “I’d say we gave them their story for thenight, don’t you?”

There were times when he could go unnoticed, slipping through the streets without heads turning or his name being repeated sotto voce as he passed. But after the fall of 1988, when he appeared on the cover of People as the Sexiest Man Alive, that happened less often. From then on, whenever a picture was published in the Post or the Star, it was more likely that strangers would approach to tell him what his father/mother/uncle meant to them. He would be cordial, graceful, and sometimes, depending on his mood, he’d thank them. Most of the time, he would just let them talk. And when they left, it would be with the sense that they knew him, that the words they had said had not been said before.

There would be a shift in him then, effortless and imperceptible to whoever was walking away, but I’d notice. It was as though a measure of spirit would leave him and then, as easy as breath, would slip back in. He had found something that had not quite been realized when he was younger -- a necessary removal that allowed him to walk this world and keep his kindness intact. Conscious of it or not, he had found a persona.