Meet the fearless labor activist who coined the positive protest slogan 'Si Se Puede'

Dolores Huerta worked tirelessly to get basic rights for agricultural laborers.

Herstory Lessons pays tribute to women whose accomplishments are hidden from history, but who have made an impact on the world. In celebration of Women's History Month, "GMA" is highlighting these hidden female figures who have made a critical contribution to our culture.

She is a rebel, a leader and a proud Latina. Dolores Huerta worked tirelessly to launch a workers' rights revolution during a time when the U.S. had a dark history buried in its farm fields.

In the 1960s, Huerta worked with labor leader Cesar Chavez on the first successful collective bargaining agreement guaranteeing basic rights for agricultural laborers where there were none before.

She coined the popular protest chant "Sí, se puede" -- "Yes, we can" -- decades before it would become an enduring campaign slogan for President Barack Obama.

Her strength and determination helped shape one of the first farmworker’s unions, and in turn, Huerta became a pioneer of modern-day social justice.

Launching the farmworkers' movement

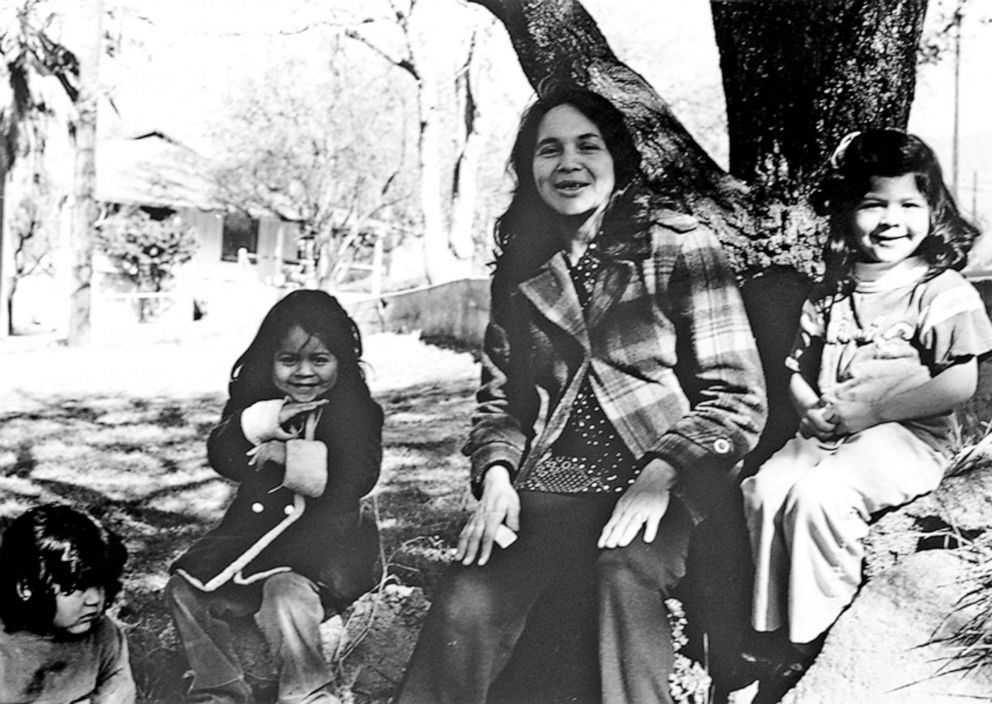

Huerta was born in 1930 in New Mexico. When her parents split up, her mother moved the family to California.

We still have that racism that exists that I had to confront when I was a teenager growing up.

Huerta said life wasn’t always easy as a Mexican-American.

"We still have that racism that exists that I had to confront when I was a teenager growing up," Huerta told "GMA."

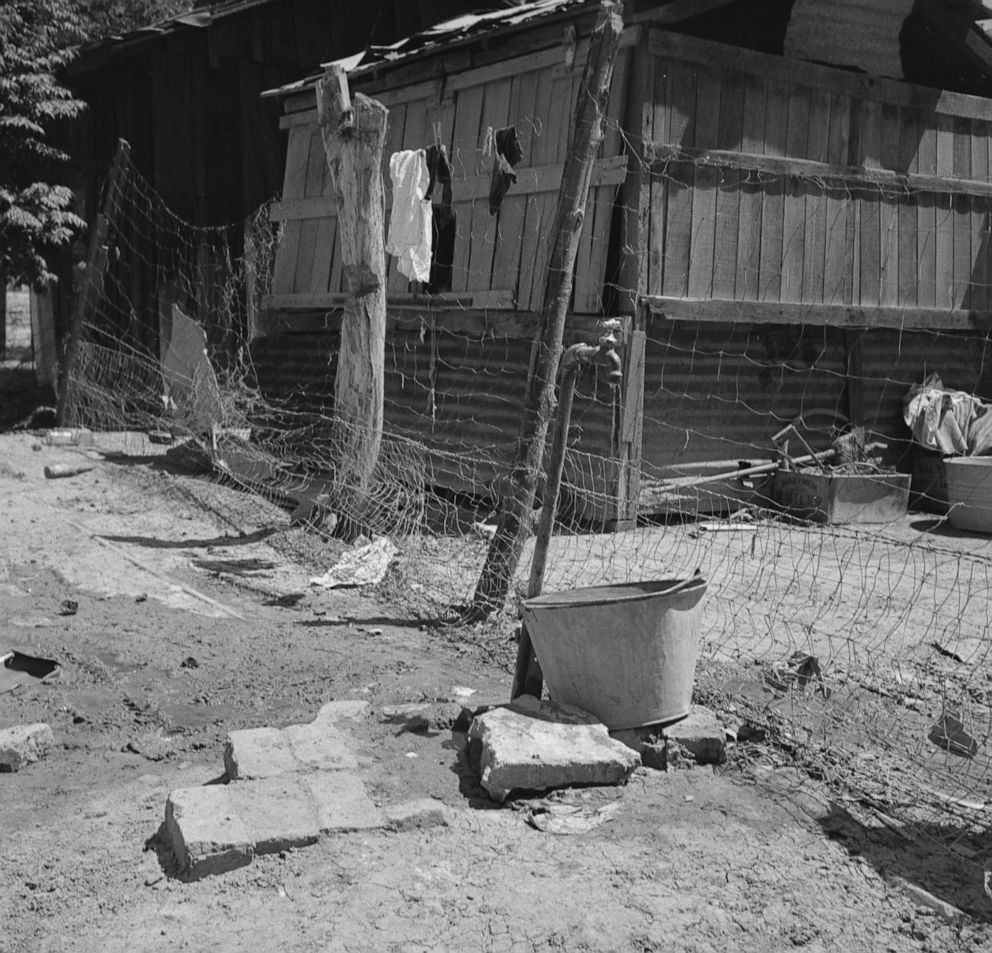

By her late 20s, she was seeing how horrendous life was for farm workers in California.

"They were only earning like 50 cents an hour," Huerta said. "They had no unemployment insurance, farmworkers, because they migrated from, you know, from county to county. They weren't even able to have any kind of access to the food banks ... no bathrooms in the field, especially for the women. That was really horrible. No access to drinking water, they would actually charge them for the water that they would give the workers and of course, no rest periods, as if they were pretty much brutalized. It was the kind of work that they had to do."

By her early 30s, she knew it was her calling to fight discrimination and help improve the lives of farmworkers. First, she joined a grassroots group called the Community Service Organization. That’s when she met Cesar Chavez and her mentor, Fred Ross Sr., who she calls the godfather of the farmworkers' movement.

By the '60s, both Mexican and Filipino farmworkers employed in the U.S. were eager for change. In 1965, they started to strike against the Coachella Valley grape growers, which became known as the Delano grape strike. And from there, the United Farm Workers union came to be.

When striking didn’t do the trick, farmworkers resorted to boycotting the grape business. They traveled far and wide to spread the word -- and companies started to respond.

"Within a few weeks of the boycott, they said, 'We don't want anybody to boycott our liquor.' So they signed the contract. So we found that it did work," Huerta said.

But reaching the entire country took time. Activists fought the corporate growers and President Richard Nixon, who was supporting the growers by sending their grapes to soldiers in Vietnam. People across America eventually boycotted grapes.

"We were able to get 17 million people to stop eating grapes," Huerta said. It took five years for key demands to be met. When the boycott finally ended, farmworkers were guaranteed some basic rights -- a first.

"These are the first farmer group contracts in the whole United States of America," Huerta said.

After everything had ended, more than 20 California grape growers agreed to start treating farmworkers more fairly.

Fighting injustice peacefully

Fighting injustice peacefully was key for Huerta. But when she was 58 years old, she encountered violence in San Francisco as she protested the agricultural policies supported by then-presidential candidate George Bush.

"[Bush] had a press conference in Fresno, California, saying there's nothing wrong with pesticides, the government takes care of people to make sure they're safe," Huerta said. "So I go up to San Francisco and we were going to protest his statement ... The police came and started beating up people in the crowd and I was one of the victims ... I broke, I think, four ribs and they didn't find my spleen. It was pulverized. They hit me so hard."

Now on the verge of death, after 30 years of activism, Huerta knew it was time to take a break.

Huerta was able to reconnect with her 11 children, some who felt like their mother had been physically absent from their lives for too long.

But Huerta would never stop working for the people.

"I actually stayed with the union for nine years after Cesar died," she said.

Discrimination and sexism were constants in Huerta's life as a woman in a male-dominated field.

Most of her life she had never thought to take credit for her work. But later on, she came to the realization that speaking in favor of women and supporting her community were critical for the future.

Social justice champion recognized for her lifelong work

In 2002, Huerta was awarded the $100,000 Puffin/Nation Prize for Creative Citizenship, and she used the money to start the Dolores Huerta Foundation.

In 2012, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Obama.

There are now seven elementary schools in California that bear her name.

And the state of California named a day for Huerta in the month of April.

Even today, her family says she is still a steadfast and tireless activist on the road, fighting for human rights, working to end racism and advocating for education.

We have a lot of work to do in our country to make sure that democracy works, and it can work.

"We have a lot of work to do in our country to make sure that democracy works, and it can work," Huerta said.

Huerta still works for equal pay for women, health care for all, and free education.

For this social justice champion, clearing a path for farmworkers and minorities to succeed has been a crowning accomplishment. But like trailblazers who came before her, Huerta realizes the fight is never over.

"We just gotta sacrifice a little bit, so that we can, you know, make our world a better place. And we can do it," she said. "But we just have to, you know, appropriate some time out of our lives, make those sacrifices to make it happen."