Gay men speak out after being turned away from donating blood during coronavirus pandemic: 'We are turning away perfectly healthy donors'

"I've been marked 'toxic' and 'not worth the risk,'" one man says.

According to the Food and Drug Administration, not all blood is equal.

Even in a time of crisis, amid a global pandemic, gay and bisexual men in America cannot immediately donate blood in the same way their heterosexual counterparts can.

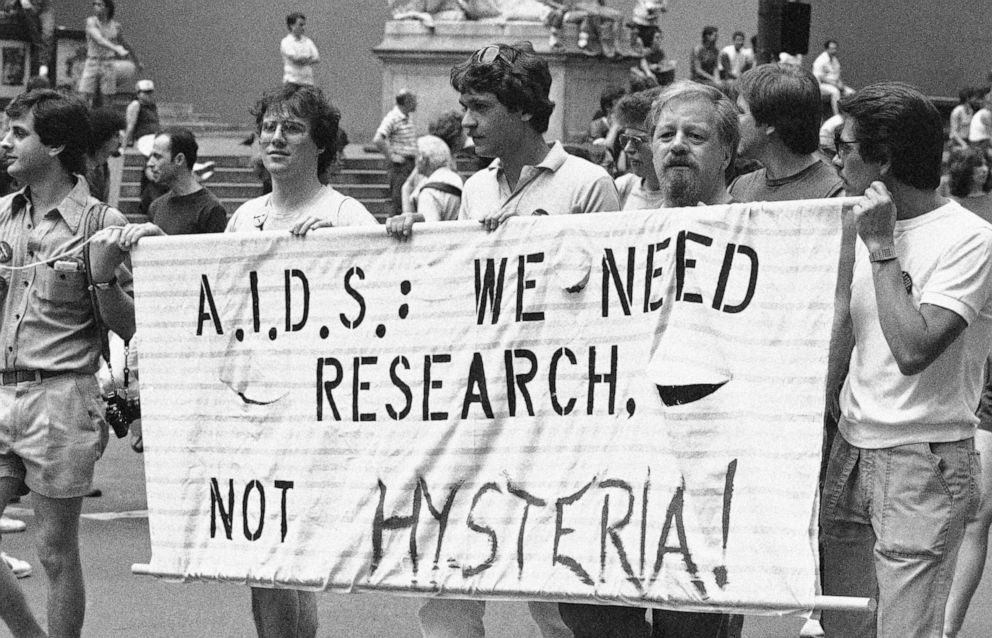

The restriction was born out of the HIV/AIDS crisis of the 1980s. The FDA implemented, in 1983, a lifetime ban on blood donations from all men who had sex with men after 1977, "to reduce the transmission of HIV by blood and blood products."

That policy was upheld through 2015, when the FDA acknowledged the improved testing technology of the time and revised the guidelines from a lifetime ban to a 12-month deferral period. Meaning, gay and bisexual men had to abstain from having sex with other men for at least 12 months before being allowed to give blood.

On April 2 of this year, the FDA revised the deferral period of gay and bisexual men, this time from 12 months to three months.

This most-recently revised FDA three-month deferral period guideline is a blanket rule for all sexually-active gay and bisexual men, even those who are in monogamous relationships, gay and bisexual men who are practicing safe sex, as well as gay and bisexual men who test HIV-negative. It also includes gay and bi-sexual men who are not exposed to HIV. All of whom must still wait three months, according to the FDA, before qualifying to give blood.

By comparison, a straight man who is in a polygamous relationship or engages with multiple female sex partners has no restrictions on giving blood based on his sexual activity.

Many doctors across the U.S. claim that any deferral period in 2020 is not only stigmatizing for the LGBTQ community, but it also limits the nation's ability to relieve itself from a critical blood shortage.

In the era of coronavirus, the FDA restrictions on gay men donating blood also extends to gay and bi-sexual men who are COVID-19 survivors who wish to donate what's called, convalescent plasma. That plasma contains antibodies which could help patients fight off the coronavirus, pending additional and emerging research.

"Really, what it comes down to is it seems like just that stigma is lingering and that's why this policy is still there," Dr. Monica Hahn of U.C. San Francisco Health told "Good Morning America."

Dr. Hahn, a family physician, specializes in HIV prevention and management and reiterated how far science has come in the last decades.

"These bans were made because it was a frightening time where we just didn't have the testing technology to adequately screen our blood supply," Hahn told "GMA."

"There's really no scientific reason anymore, in my opinion, to have this ban at all since our testing capacity has been truly revolutionized," Dr. Hahn added.

In a statement to "GMA" in April, the FDA said they were working on gathering data that could lead to individual risk assessments for for all donors wishing to donate blood and/or plasma, rather than following restriction guidelines for a community of individuals alone. The FDA however, provided no additional detail on a timeline or specifics on the data needed to drive their decision-making.

As lingering stigma takes on modern medicine and technology, "GMA" asked several healthy gay men who have been turned away from donating blood on the basis of their sexual identities to share their experiences and unique perspectives.

One of the men, whose story was first reported in the Miami New Times, describes how he feels his universally-accepted O-negative blood is rendered useless because current FDA regulation prohibits him from giving his blood with the same immediacy as straight people.

Here are their stories, in their own words, about why it's important for them to have the right to give blood or plasma without restriction or pause...

David Grimes | Tallahassee, Florida

I still remember freshman year of college when I went with some friends to the bloodmobile at the student union and found out that I would no longer be eligible to donate blood.

I sat down and we were going through the intake questions when I got to the, "Are you a man who's had sex with men?" question. I asked the staff about the question and they explained to me that as a gay man who is sexually active, I would not be able to donate blood. I had no idea before that moment that there even was a ban. I got to find out in front of my friends and everyone who was at the union to donate that day.

I suppose I have never been eligible to donate blood as an adult, but I didn't know that. The folks at the bloodmobile were very apologetic, but it was a stark wake-up call to me that to lots of people in the world, the LGBTQ community is still the "other." It was also the beginning of my LGBTQ advocacy work.

LGBTQ folks in the country still have a long way to go to live up to the promise of America.

Giving blood doesn't seem like a big deal to a lot of people. When I think of giving blood, it's such a phenomenal way to support our human family. It's an intimate giving of your actual body to a stranger. It's something that can't be produced in a lab or manufactured in a factory -- only we can do it for each other. In a time of national crisis like the one that we're in now, it's more important than ever that we are all able to support each other.

It's not just the degrading experience of being turned away and being publicly discriminated against that's the problem either. On a pragmatic note, I don't know my blood type. Most folks I know got that information donating blood. Not me.

Years after that freshman year of college, my sister got to see me turned away from giving blood when I accompanied her, once again, to that fateful bloodmobile.

I told her about my experience finding out about the gay blood ban in college and we talked a bit about what it was like for me and what the ban meant to me.

She is still upset to this day. That morning when we walked past the bloodmobile, she insisted I come with her to donate. I tried to explain that they wouldn't be able to accept my donation, but she wasn't having it. She could not believe that there was such a blatantly discriminatory law on the books in modern America. To this day, she hasn't donated again.

The fact that even after the official donation policy has changed and I have been eligible to donate blood according to the new policy after abstaining from sex for three months, I cannot find a donation center in my entire region that has updated their policies to match the FDA to accept my blood. It's heartbreaking.

It's a stark reminder not just of the difficulties of bureaucratic inertia, but that there are people out there who don't care about facts and don't care about science, and would literally rather risk someone's life, maybe even the life of someone they love, rather than accept gay blood. Blood that is indistinguishable in every material way from every other blood donation except that it came from the body of a gay man.

It's a reminder that despite all our victories, LGBTQ folks in the country still have a long way to go to live up to the promise of America.

Lucas Horns | Salt Lake City, Utah

My partner and I both tested positive for COVID-19 relatively early. We were fortunate enough to recover quickly and once we did, many people started asking if we were planning on donating our blood and/or plasma.

It makes sense why they'd ask -- there was a lot of buzz at the time about using the antibody-rich blood of those who've had COVID-19 to treat high-risk patients.

However, they were all pretty surprised when they heard our response: "We can't. We're gay."

It takes me back to when I was bullied as a kid and was accused of having AIDS and being able to spread AIDS to other kids just because I was gay.

I've always known about the FDA regulation that prohibits sexually active gay men from donating blood, but it never affected me because I'd never had an overt desire to donate.

Now that my partner and I have a unique opportunity to potentially save lives with our blood, it's extremely frustrating to not be allowed to. I want the antibodies in my blood to be used for good, but instead it feels like they're being wasted.

Antibodies aside, blood is in higher demand than usual, and I wish I could help, but every time a commercial comes on asking for donations, it's almost insulting because it feels like they're saying, "We really need blood, just not from you."

The regulation is based on the outdated stereotypes that all gay men are HIV-positive; however, it's pointless for a number of reasons:

- Anyone can carry, HIV, not just gay men.

- Many steps have been taken in large success to reduce the spread of HIV in the gay community.

- All donated blood is tested for HIV and other viruses anyway.

Not only is this regulation senseless, but it's hurtful.

It takes me back to when I was bullied as a kid and was accused of having AIDS and being able to spread AIDS to other kids just because I was gay.

This sort of narrative made me feel dirty or gross for being gay.

This regulation, that judges an entire community of people, no matter their HIV risk, is founded on the same sensibility those bullies had and inflicts the same sense of shame they made me feel.

Every American should want to repeal this nonsensical, discriminatory rule. It's keeping a huge proportion of the population from donating blood and plasma. Now, more than ever, we need everyone who's able to donate to do so, especially if your blood, like ours, can be used for life-saving research.

Kevin Restrepo | Miami, Florida

'At the time, I couldn't get married because I was gay. Giving blood was just something else I couldn't do because of who I was, so I accepted it and moved on.'

I never really cared much about not being able to donate blood.

It was just one of those things I couldn't do, so I never bothered to look into it, even though I knew that I had type O-, which is the universal one.

I found out about the blood ban when I was 17.

They told me that I couldn't donate blood if I had any sexual contact with a male. I didn't really think much of it. At the time, I couldn't get married because I was gay. Giving blood was just something else I couldn't do because of who I was, so I accepted it and moved on.

I thought, "Why would I give my blood to people that don't want it?"

That changed after the Pulse nightclub shooting.

I knew I wanted to help my community, but I was limited in what I could do.

I mean, I could have lied about who I was so I could give blood, I know plenty of people who did that, but I knew it could potentially be a crime.

In the end, I felt powerless in not being able to help when I wanted to most.

Even if I had HIV or any bloodborne illness, the FDA says that all blood is tested when it's donated.

It pissed me off that I couldn't help because out of some outdated notion that because I have gay sex, I'm "dirty." That if we had leadership that gave a damn about us during the '80s, we wouldn't even need those type restrictions to begin with, which is also hypocritical since anyone can get HIV or an STD, not just gay men.

Why aren't they asking of straight people when they donate blood if they had safe and protected sex?

As for this pandemic it's frustrating especially now, in a climate where the current administration is rolling back legal protections against trans individuals. On top of that, coronavirus is disproportionately affecting Black, Indigenous, people of color and LGBTQ people. And I'm still being restricted on being able to help them based on outdated restrictions.

It is frustrating having my hands tied when it comes to providing a level of aid to my community on something that seems so mundane to me.

Most people won't think twice about donating blood.

Like, it's just something you can do on the fly, or even as a feel-good thing you might do on your day off.

If my words and my story can contribute even a little bit to bringing positive change, then why not do it and speak out on my experience?

To me, I feel like it's my duty to share my experience.

It's time to speak up.

Lukus Estok | New York, New York

What is the value of helping someone in need?

That's what comes to mind when I'm asked why it matters if I can donate blood or plasma as a gay man during the pandemic.

Why is it important that we help one another? Why is it important that we not continue to stigmatize one another? Because lives are on the line. Because it's the right thing to do. Because we know better.

...in that moment of rejection, a lifetime of shame washed right back over me...'Why did I tell them what I am?' I thought.

There were no lessons on LGBTQ history given to kids in the Midwest, or anywhere, in the '90s. I had almost no notion of what it meant to be a gay man as I grew up, unless it was within the context of someone discussing AIDS. Having AIDS and being gay was synonymous my entire life. It's in service to that horrific and painful legacy that I'm deemed high-risk in donating my blood or plasma in the United States. Simply because of who I am, the federal restrictions of today handed down from decades-past make me feel that I've been marked as "toxic" and "not worth the risk."

By the time I recovered from COVID-19, the world had been locked down. After weeks of struggling, what I really wanted was to be useful. I wanted to help. When the FDA announced that it was slightly relaxing the deferral on gay and bisexual men donating blood and plasma, I realized I finally qualified. It was an opportunity!

I re-tested as negative for the virus, had samples of my blood tested for antibodies and passed two rounds of donor screening questions. I was labeled a prime candidate to donate convalescent plasma intended to help those suffering. This gave me such a sense of purpose, I was excited and more than a little nervous.

It wasn't until I was checking in at the donation appointment that I let it slip I was a gay man. Publicly and without hesitation I was told that mine was not a donation they would accept. I was immediately rejected.

I have now spent half of my life living in New York City. Discovering who I am, learning some of our history, and building a sense of community and even pride in my identity. But in that moment of rejection, a lifetime of shame washed right back over me. I argued and yelled. My emotions got the better of me and I cried. It felt like a punch to the gut. I even found myself blaming myself. "Why did I tell them what I am?" I thought.

But that was wrong. That's the tragic end result of what institutionalized discrimination does. It seeps into our very identities without us even realizing it. Here we were in a global health crisis, I'm trying to help and I'm blaming myself for my country treating me like a second-class citizen. I felt deflated.

We're allowing an outdated stigma to keep us from giving life-saving assistance in the form of being qualified donors. We need to end the practice of barring people from donating life-saving blood or plasma based on who they are in favor of individual, risk-based standards. Medical science has advanced since the '80s, it's possible for us to discern viable candidates by assessing risk factors on an individual level.

This doesn't need to be political or controversial, but it is moral. People are dying, yet we are turning away perfectly healthy donors. We need this change and we need it implemented with reasonable haste. Administrative red tape is insufficient. We are still in the middle of a global health crisis, with blood and plasma reserves often nearly depleted.

Yes the FDA, under pressure, has announced that it will launch a pilot program to consider changing the assessment standard. Instead, I'd like it to listen to the medical and health care professionals who have been standing up and speaking out. Those professionals say that additional study and data are always welcome, but the data we have clearly supports a change. We need the FDA to listen to the experts and do the right thing.

What would it mean for me to see one less discriminatory policy? What would it mean to see science, not stigma, win the day? It would give me hope knowing that countless additional people were receiving life-saving transfusions and treatments. It would be a victory for this country when queer people are seen as just people, worthy of equal dignity and respect.

Sure, we still have a ways to go before we get there, particularly for anyone who is not a cisgender white man. But any progress is welcome. Hope and equality, we could use a bit more of them right now.

Josh Shutkind | Salt Lake City, Utah

'To me, this pandemic is so much greater than identity, it's about humanity.'

I imagine most people never believed they would experience a global pandemic. But something that started out on the other side of the world has suddenly become a global emergency.

Which leads us to now, a time when solidarity and the pooling of resources have never been more crucial.

To me, this pandemic is so much greater than identity, it's about humanity. Gender, race and sex should have no place in the discussion of how we, as society, should combat and overcome the devastation the coronavirus has caused.

As a gay man who has survived COVID-19, it is shocking to me how an outdated regulation could deny me the ability to donate blood for what will one day be a life-saving vaccine.

It is difficult for me to understand, as a healthy, young, sexually-committed individual, why I am unable to contribute my blood or my plasma during a time of crisis to potentially save the lives of others battling this incurable disease.

I think about my loved ones and can't imagine this virus taking their lives.

I'm motivated by knowing that very reality is tangible among everyone right now.

To understand that fear, and be incapable of offering something which is sorely needed on the front lines, makes me feel not only powerless, but marginalized.

My hope is that when we have found a way past this, everyone can stop and reflect on how we could have done better.

Being gay should not restrict a human being from contributing what they can, especially in a time when most of us are feeling scared and are needing each other more than ever.

The views and opinions expressed in this article belong solely to the author and do not necessarily represent the views of ABC News or "Good Morning America."

Editor's note: This was originally published on July. 2, 2020.