How bingo is helping survivors of the Buffalo massacre cope

"It's just a moment to let your shoulders down," one Tops worker said.

BUFFALO, N.Y. -- It started as a stress-relieving activity borne out of group therapy following the mass shooting at the grocery store where they work on the east side of Buffalo. But once those counseling sessions ended, some Tops market workers said they have continued to make bingo part of their healing journey.

They said it gives them a chance, for at least a few hours every week, to get their minds off the racially motivated May 14 massacre that left 10 people dead, three wounded and many others traumatized.

"It's not something where you always have to come up with a conversation piece because you're doing something. You're busy, like your brain is busy doing something," one Tops worker, Fragrance Harris Stanfield, told ABC News. "But you're also there with each other. It's just a moment to let your shoulders down."

Respite from agony

On a recent Thursday night, several Tops workers gathered at their new favorite bingo-playing spot -- the Blessed Trinity Catholic Church hall in Buffalo. They joined about 150 players in total, sitting at long tables in the sprawling room.

With a colorful array of bingo daubers, the participants filled in squares of their game cards as they paid close attention to an announcer reading numbered balls drawn randomly by an old-timey-looking electronic machine.

"I-20, B-52, O-70...," the announcer said into a microphone in rapid succession, prompting Harris Stanfield's close friend and Tops co-worker Toy Benefield to exclaim, "I feel it in my bones" as she dabbed her card in anticipation of a stroke of luck.

"Bingo!" someone yelled near the back of the room, producing groans from players who didn't win.

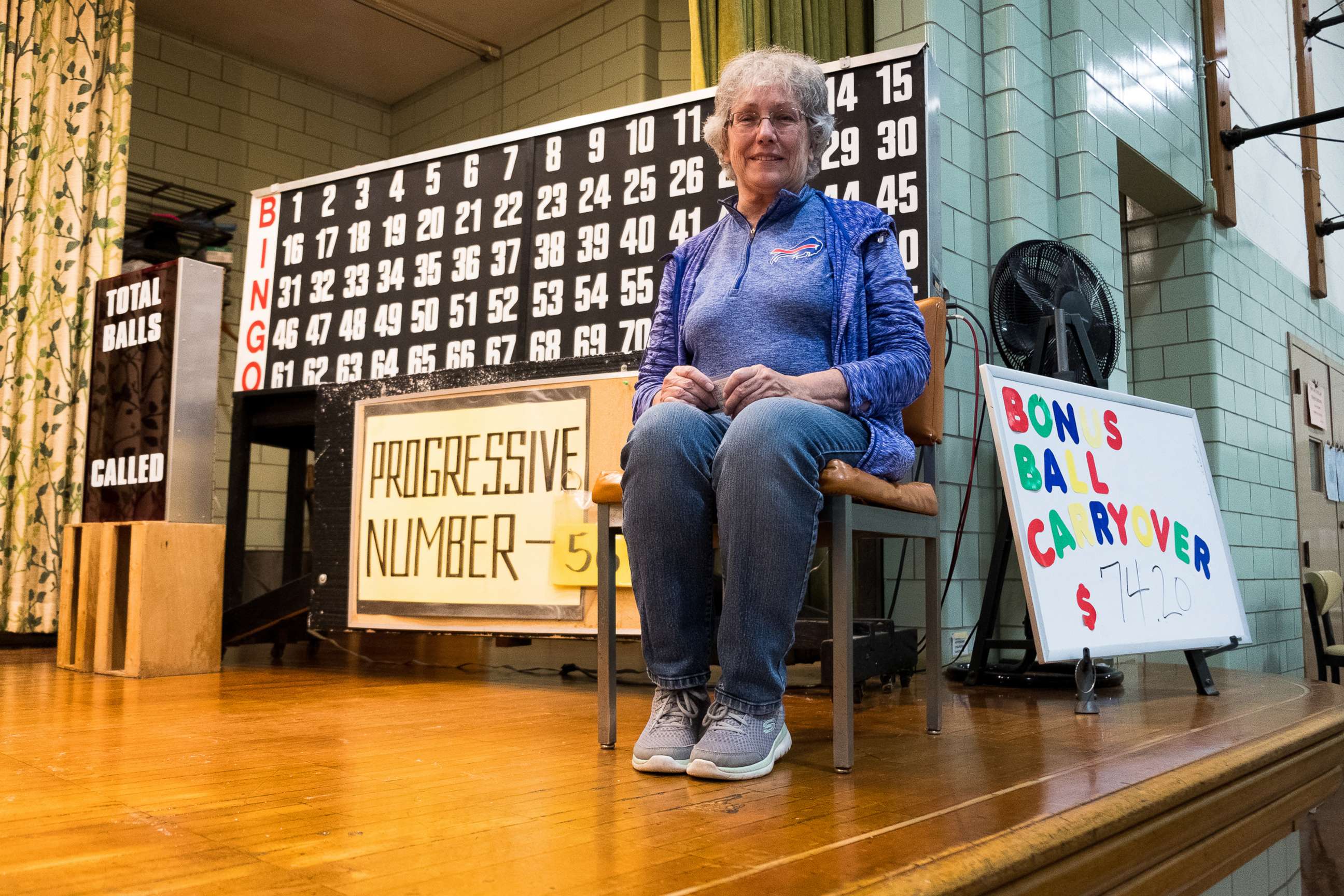

Kathy Press, who runs the weekly bingo sessions to raise money for Blessed Trinity, said the church's game dates back at least 60 years and that she understands how playing it can be a stress-reducing activity.

"Every Thursday, I would say 90 to 95% of the people that come here are repeats. And not that we serve alcohol, but it's like a neighborhood bar. Everybody knows everybody and, for the most part, everybody's really friendly," Press told ABC News. "Everybody, of course, is here to win. But I think they're also here for the socialization, getting together and seeing their friends at least once a week."

Benefield said she used to attend bingo nights at the church years ago, and only found a new fondness for the game following the mass shooting at Tops.

"I enjoy it. So, I just kind of make Thursdays my day to come to bingo," Benefield said.

She said that following the shooting, a co-worker mentioned in group therapy that she'd been going to bingo games at Blessed Trinity on Thursdays.

"So, a few of us came," Benefield said. "And what's crazy is I came and I won. I won the last game, but I had to split it. The jackpot was $250."

Harris Stanfield said she didn't get into bingo until she and her colleagues started playing the game at the end of each of their group therapy sessions held in a library near the east side Tops store in the immediate aftermath of the rampage.

"We had our own Tops version of bingo, where like the letter T is one of the ways that you could win," Harris Stanfield recalled.

She and Benefield said the games became a respite from the heavy topics they discussed in therapy, and an excuse to get together and catch up.

"After those sessions were over, everyone said, 'We're really going to miss being with each other.' That was one of the highlights because we just had so much fun and just the camaraderie of playing a game with your co-workers," Harris Stanfield said.

'It could have been me'

On the day their store was targeted in what prosecutors have called a racially motivated attack, Harris Stanfield said she was supervising a crew of cashiers at the front of the store, working at a register next to a quick-scan checkout counter where her 20-year-old daughter, Yahnia Brown-McReynolds, who had just come back from maternity leave that week, was stationed.

During the chaos that ensued, Harris Stanfield said she and her daughter got separated. It wasn't until after the shooting ended and the suspect, Payton Gendron, was arrested, that she found her daughter physically unharmed outside the store.

"In a very grim situation, I was relieved that she was OK," said Harris Stanfield.

Harris Stanfield said that since the shooting, she has struggled with psychological trauma, frequently battling depression. She continues to have individual therapy sessions, she said.

"It's a heavy situation to live with. It's not that you wish you died. It's not that you have remorse that you lived. It's that you are living with this and you have to find a way in your mind to be OK with that. You have to be OK with the fact that you've made it out," Harris Stanfield said.

Benefield said she left work just moments before the shooting started, but believes she may have crossed paths with the gunman on her way out of the parking lot.

When she walked out of the store that day, she said the last person she spoke to was Aaron Salter Jr., the armed security guard and retired Buffalo police officer, who was killed while confronting the gunman.

"His last words to me were, 'I'll see you tomorrow,'" Benefield said.

The shooting, she said, unearthed memories of the death of her 28-year-old son, Reginald Barnes, seven years earlier.

"My son lost his life by gunfire. I still don't know who did it," Benefield said. "So, when this took place at Tops, I sit and I say, 'Wow, why?"

Even though she was not present when the shooting occurred, the event weighs heavily on her mind.

"It could have been me, I could have walked right out into it," Benefield said.

Benefield said she has returned to work at the store and also to her job as a teacher's aide for the Buffalo public schools, but misses her colleagues who have not come back to work, including Harris Stanfield.

She said bingo night is a chance to meet up with Harris Stanfield and a handful of Tops workers and swap stories about the latest Buffalo Bills game, their children, grandchildren and whatever else is going on in their lives.

"Coming here, our minds are focused," Benefield said. "It's like everything else is just blocked all out. We're just in the moment."