A new treatment could deal '1, 2 punch' to Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and other incurable cancers

Turning tumors into a vaccine.

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is a unique cancer that originates in the white blood cells of the human bone marrow. It is the seventh most common cancer in the United States and an estimated 75,000 cases are diagnosed each year. The five-year survival rate is 71 percent, according to the National Institutes of Health.

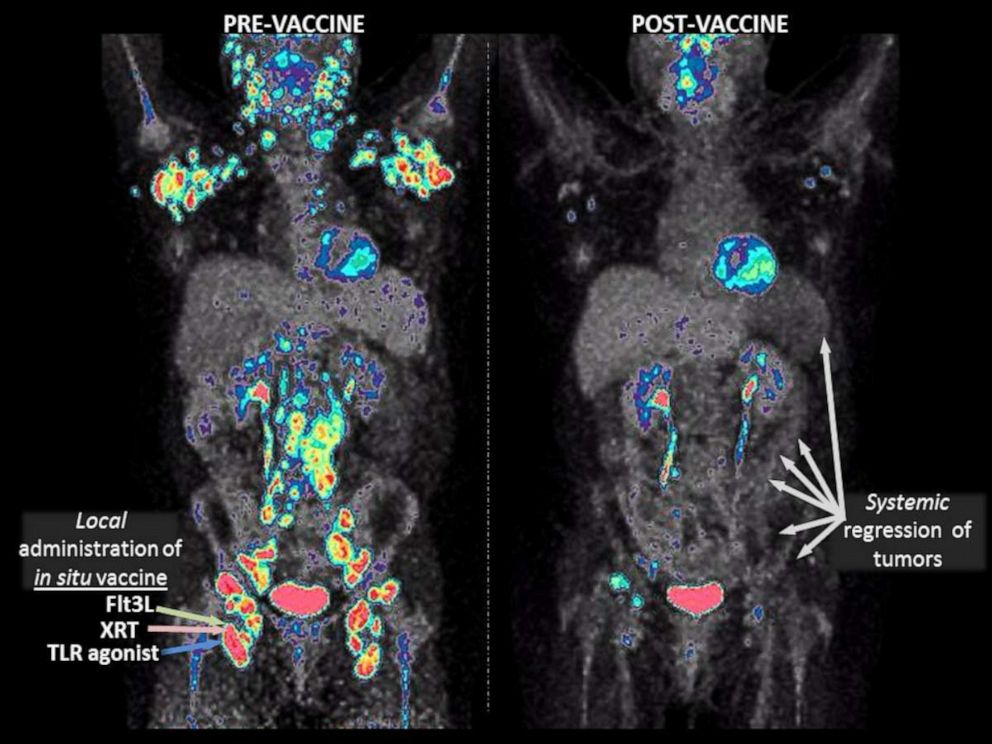

Researchers at Mount Sinai in New York have used a form of NHL to develop a novel approach to cancer immunotherapy, injecting immune stimulants directly into a tumor to teach the immune system to destroy it and other tumor cells throughout the body, Dr. Joshua Brody, director of immunotherapy at Mount Sinai, told ABC News.

“While most vaccines we think about (like polio vaccine) are preventative, researchers are also developing therapeutic cancer vaccines, which can treat people who have already developed the disease,” Brody said.

The vaccine works by taking advantage of rare but powerful immune cells called dendritic cells, which were the subject of the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

“Dendritic cells are the generals of the immune army and give orders to T cells -- the immune soldiers -- on which cells to ignore and which to attack,” Brody said.

The immunotherapy vaccine is composed of three parts: two immune modulators and radiotherapy.

“This is like a 1, 2 punch of treatment that primes the immune system then activates it to seek and destroy tumors,” according to ABC News’ Chief Medical Correspondent Dr. Jennifer Ashton.

The study is still in early clinical phases and has been tested on 11 patients with indolent non-Hodgkin’s B cell lymphoma.

Brody said the patients tolerated the treatments well.

“The only real side effect was that some patients had fevers lasting for a few hours to a day along with achy muscles, similar to what some people get after a flu vaccine. Actually, patients that did develop a fever were a bit more likely to have regressions of their cancer,” Brody said.

And early results have been very positive, providing prolonged remission rates in these patients.

“The vaccine was remarkably effective in patients with advanced-stage lymphomas -- a generally incurable disease. Not only did the injected tumors melt away in most patients, but some patients experienced regression of non-injected tumors throughout the body, yielding partial or complete remissions lasting months to years,” Brody said.

A similar but different type of immune therapy called checkpoint blockade is already FDA-approved and fairly effective for some types of cancers, though it has limited effectiveness in lymphomas and other cancers, such as breast cancer.

In early clinical trials entailing animal studies, checkpoint blockage alone cured zero percent of cancer cells. The addition of the immunotherapy vaccine allowed for 75 percent cure rates, Brody noted.

Brody said the results were so promising, he and other researchers have now started a follow-up trial combining the vaccine with the checkpoint blockade therapy for patients with lymphoma, breast cancer and head and neck cancer.

“If the results are as remarkable as what was seen in the lab, it could provide real benefit for these patients," he said.

Ashton said the innovative treatment is promising but notes it’s very early in testing.

“It's still in early clinical and animal trials and needs a lot more testing before being approved for widespread use," she said.

Nura Orra is a family medicine physician at the Case Western Reserve University/Metro Health Medical Center and is a member of the ABC News Medical Unit.