Blaming mass shootings on the nation's mental health crisis is 'harmful', advocates say

1 in 5 adults in the U.S. experience mental illness each year, estimates show.

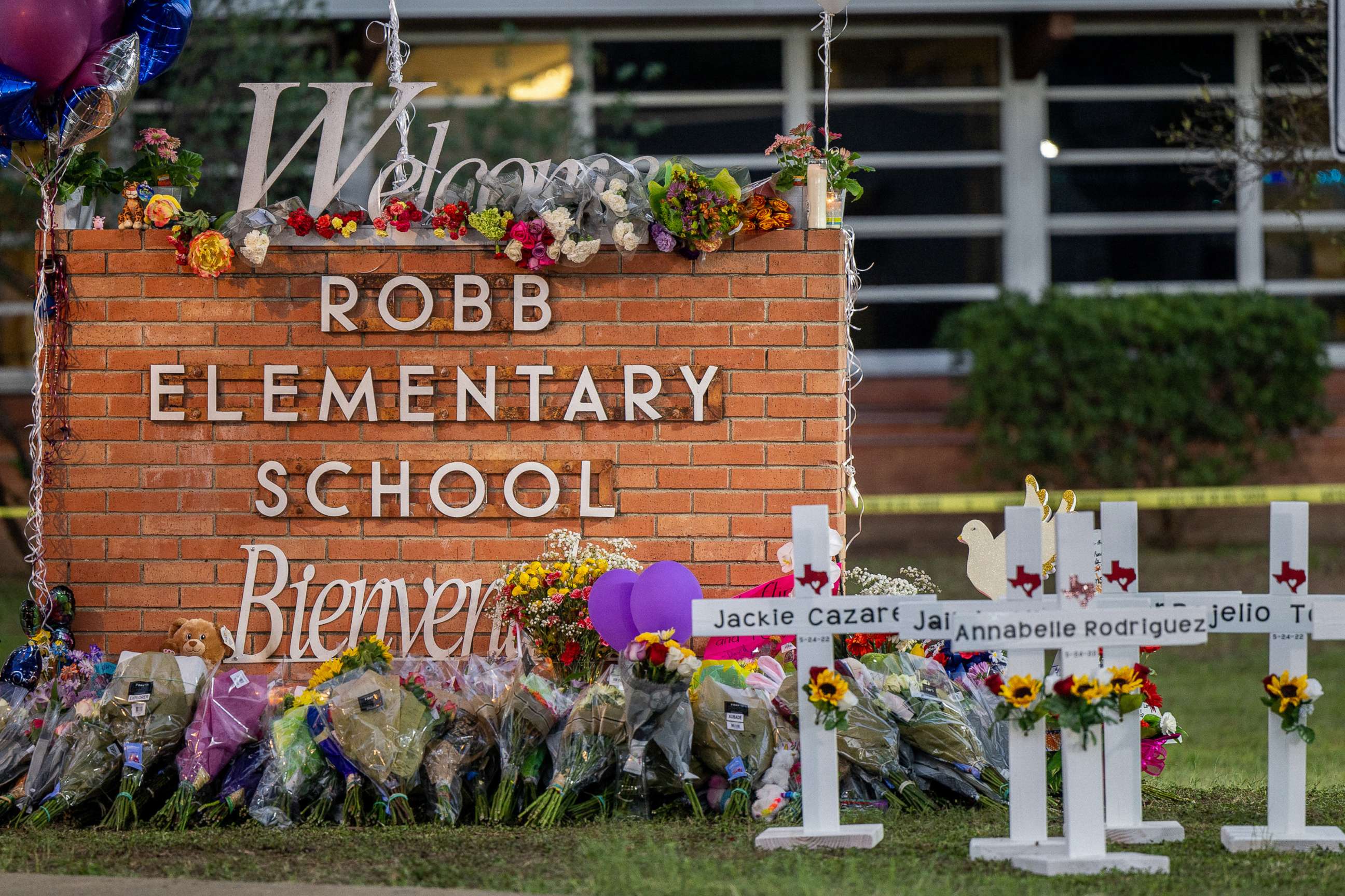

Tuesday marked yet another tragic day in America, after a gunman opened fire at an elementary school in rural Texas, leaving 19 children and two teachers dead, and dozens of family members and friends in mourning.

As the nation reels from the tragedy, politicians and pundits have been pointing fingers as to who and what is to blame for these relatively rare but increasingly common public mass casualty events.

At the forefront of the debate is the role of mental health in these incidents, with some legislators asserting that such atrocities are the result of the nation’s mental health crisis.

"We have a problem with mental health illness in this community," Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said on Wednesday.

However, physicians, psychiatrists and other leading experts told ABC News that it is inaccurate to assert that "mental health issues" are solely or primarily responsible for the United States’ ongoing rash of gun violence.

Instead, while experts say some aspects of mental illness are associated with mass violence, they insist that it is truly a multi-layer and complex crisis, driven by a confluence of other factors as well, such as widespread access to firearms, stalled gun reform and exposure to increased stressors and crises.

“There is no ‘the mentally ill.’ It’s all of us. It’s our kids, our families, our uncles, our cousins,” Joel Dvoskin, a clinical and forensic psychologist who served on the American Psychological Association's Task Force on Reducing Gun Violence told ABC News.

“These events slap us in the face… This is a public health crisis, and we should think of it as a public health crisis," Dvoskin said in reference to the gun violence and Tuesday's tragedy in Uvalde.

In fact, a 2018 report of the FBI on the characteristics of active shooters found that only 25% of shooters from 2000-2013 had confirmed mental illness.

"There are important and complex considerations regarding mental health, both because it is the most prevalent stressor and because of the common but erroneous inclination to assume that anyone who commits an active shooting must de facto be mentally ill," the report said.

"Absent specific evidence, careful consideration should be given to social and contextual factors that might interact with any mental health issue before concluding that an active shooting was 'caused' by mental illness. In short, declarations that all active shooters must simply be mentally ill are misleading and unhelpful."

Millions experiencing mental illness in the US

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, approximately 1 in 5 adults in the U.S. experience mental illness, defined as a condition that affects a person's thinking, feeling or mood, each year, approximately 52.9 million Americans. In 2020, 1 in 10 young adults, between the ages of 18 and 25, were found to experience serious mental illness.

With millions of Americans grappling with mental health challenges, doctors and public health experts, interviewed by ABC News, questioned whether it would be feasible to rely on the nation's current mental health infrastructure to stop would-be shooters.

“The notion of blaming this on the mentally ill is an intentionally disingenuous scapegoating of people who have enough problems already -- that they don't need to be insulted by politicians who were looking for a way to avoid a more complicated discussion,” Dvoskin said.

Those who live with mental illness are 10 times more likely to be victims of crime than perpetrators, he added.

“Very few of these mass shooters have had a diagnosed mental disorder of any kind. That doesn't mean that they were doing fine. I think the better rhetoric to use [instead of] mentally ill is people who are in crisis. Anybody who's in a crisis of despair or rage… that doesn't mean they're going to shoot anybody but they ought to get help,” Dvoskin said.

On Wednesday, the National Alliance on Mental Illness also pushed back on the notion that mental illness is at fault in this shooting or with other similar crises.

“Mental illness is not the problem. It is incorrect and harmful to link mental illness and gun violence, which is often the case following a mass shooting,” the organization wrote. “Pointing to mental illness doesn’t get us closer as a nation to solving the problem and doing so leads to discrimination and stigma against those with mental illness — who are more likely to be victims of violence than perpetrators. People across the globe live with mental illness, but only in the U.S. do we have an epidemic of senseless and tragic mass shootings,” they said.

Globally, estimates suggest around 1-in-7 people have one or more mental or substance use disorders.

However, even with the pandemic impacting people across the globe, the United States is unique in its epidemic of gun violence, with the nation reporting more violent deaths — largely driven by firearms — compared to other high-income countries.

One study found that the U.S. gun homicide rates were 25 times higher than in other high-income countries.

"If mental illness were the simple cause, you'd see mass shootings happen all over the developed world," Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) said this week.

Politicians fight over the role of mental illness in mass casualty incidents

Many politicians on the right, who are ardent defenders of gun rights, point to mental health as the principal issue at hand.

Although officials reported that the gunman had “no known mental health history,” Texas Gov. Greg Abbott stressed on Wednesday that mental health issues must be addressed in order to evade such tragedies in the future.

“We as a state, we as a society, need to do a better job with mental health. Anybody who shoots somebody else as a mental health challenge, period. We as a government need to find a way to target that mental health challenge and do something about it,” Abbott argued during a press conference.

Following other mass shootings in years prior, former President Donald J. Trump, shared a similar sentiment in placing the blame on mental illness.

"Mental illness and hatred pull the trigger. Not the gun," Trump said in the days after two mass shootings in El Paso, Texas, and Dayton, Ohio, in 2019.

However, on the other side of the aisle, many Democrats have rejected such an argument as an excuse to not address gun reform legislation.

“Spare me the bull---- about mental illness,” Connecticut Sen. Chris Murphy, a Democrat, who, when he arrived in Washington, D.C., first represented the district home to Sandy Hook Elementary. “We don’t have any more mental illness than any other country in the world. You cannot explain this through a prism of mental illness because we’re not an outlier on mental illness.”

Mass shooting incidents increased during the pandemic, data shows

In the last two years, conversations around mental health and the potential impact on mass casualty incidents have been augmented by the onset of the pandemic.

Since the early days of the pandemic, officials have been warning that COVID-19 could cause spur an uptick in violence across the country.

An internal Department of Homeland Security memo in early 2020, obtained by ABC News last summer, warned that the emotional, mental and financial strain, exacerbated by the new pandemic, combined with social isolation may "increase the vulnerability of some citizens to mobilize to violence."

Thus, the question of what role COVID-19 may have had in exacerbating these already existing issues surrounding mental health, isolation, and radicalization, is one that groups of public health experts have been investigating as the frequency of these mass shooting events has increased.

Dr. Anupam B. Jena, Associate Professor of health care policy at Harvard Medical School, who has been studying the rash of mass shootings across the country, told ABC News that since the onset of the pandemic, there has been a clear increase in the number of mass shootings, defined as shootings in which 4 or more people were killed or injured, not counting the perpetrator, when compared to previous years. Totals for 2021 were even higher than those seen in 2020, according to Jena's research.

“It's very clear that something has changed during the pandemic that has led to an increase in mass shootings and the timing of the increase is timed, really at the start of the pandemic,” Jena said. “I feel pretty confident saying the increase in mass shootings that we've observed in the last year and a half two years is a result of changes that have occurred during the pandemic."

CDC data, released earlier this month, found the overall gun homicides increased 35% across the country during the first year of the pandemic to the highest level in 25 years.

According to an analysis, conducted by Jena, there were 343 more mass shootings "above expected," during that period, leading to an additional 217 deaths, and 1,498 people injured, between April 2020 and July 2021.

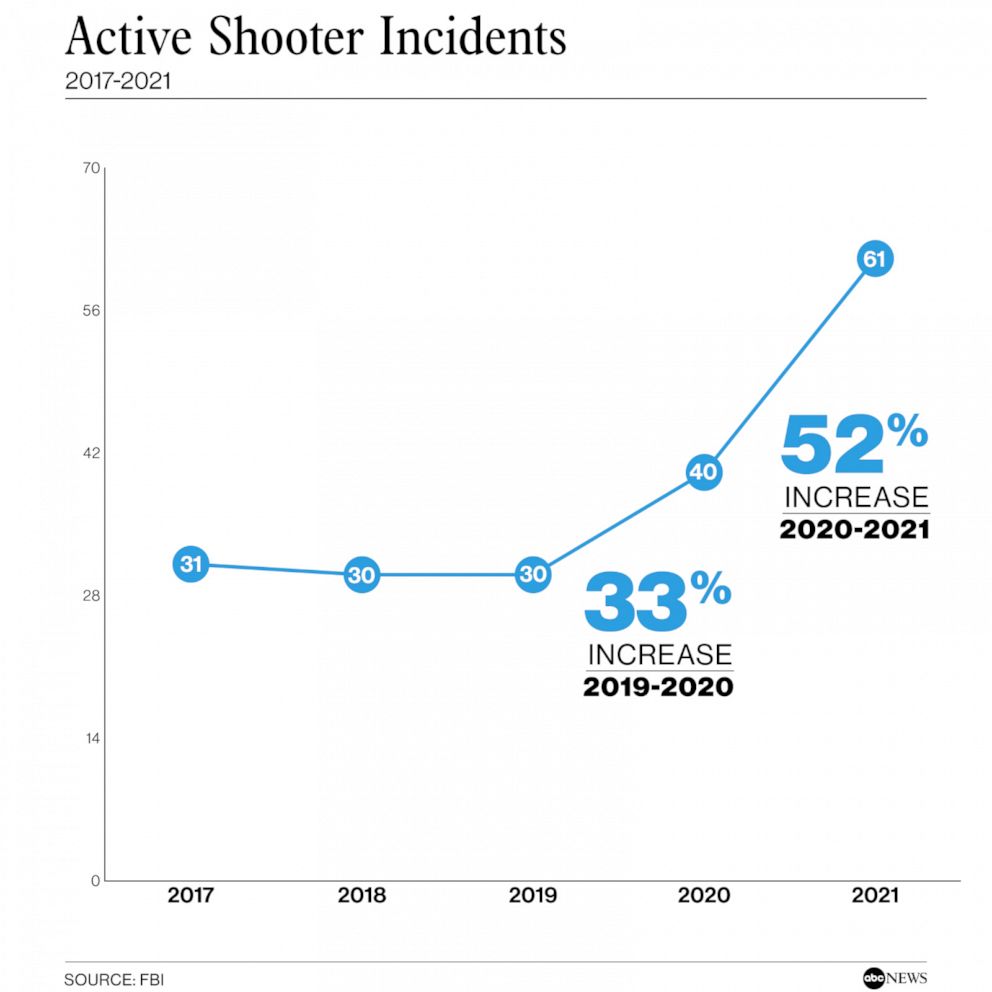

An FBI report released on Tuesday also revealed a 52.5% increase in active shooter incidents between 2020 and 2021. Such incidents have increased by nearly 100% since 2017.

“The COVID-19 pandemic imposed sudden and additional psychological and financial strains across society through fear of death, social isolation, economic hardship, and general uncertainty,” and thus, the tremendous tensions and stresses caused by the pandemic could have led to an uptick in mass shootings,” Jena and his co-author wrote in a September study.

Economic and social factors played a significant role in the likelihood of a person committing a mass shooting, Jena argued.

“There's not a person who hasn't been disrupted by the pandemic really, and so the question is does it have a particularly pronounced effect on people who would be prone to committing acts of mass violence, and it seems to be that way,” Jena said.

As with COVID-19, there is a “contagious” nature with mass shootings, according to David Hemenway, the director of the Harvard Injury Control Research Center, with incidents at times having a domino effect, one occurring after the other.

The pandemic has had ‘enormous’ effects on mental health

The pandemic itself has had “enormous” effects on the mental health of people across the country, Hemingway said.

Public health experts say social disruption caused by the lockdown, and by all the changes in the way society operates, has affected everyone, regardless of race, gender or age.

“It's been a time of terrible disruption,” Dr. Rebecca W. Brendel, the president of the American Psychiatric Association, told ABC News. “All the institutions and the support and the connectedness that holds us together, was taken away overnight, and it's simply just not back the same way again. How could it not disrupt our lives in ways we're only beginning to understand?”

The vast majority of attackers in mass attack incidents — 87% — had at least one “significant stressor,” defined as significant medical issues, turbulent home lives, work and school issues, strained relationships, and personal issues, within five years leading up to the attack, according to a United States Secret Service report on Mass Attacks in Public Spaces.

However, the USSS reported noted that "the vast majority of individuals in the United States who display the symptoms of mental illness discussed.... do not commit acts of crime or violence."

People rely on regularity to protect the predictability, the connectedness of our institutions and our relationships, for a normal healthy development, Brendel said.

“Part of normal development is learning how to interact with other people and learning about one's place in the world, from being around other people and navigating relationships in person,” she said, and a number of things have gotten in the way of that normal development.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, 1 in 5 people reported that the pandemic had a significant impact on their mental health, including 45% of people with mental illness.

Young people have been particularly affected, data shows. During the pandemic, more than one-third of high school students in the U.S. reported experiencing poor mental health during the pandemic, while nearly half of students, 44%, reported feeling persistently sad or hopeless in the past year, according to data released by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

One significant culprit that continues to aggravate these feelings of loneliness is social media, said Brendel. Although it serves as a way to keep in touch, it can also lead to problematic situations.

“We're seeing kids who get their information, or see their friends only through social media posts, and we know that people can portray themselves only as they wish to be seen,” Brendel said, adding that this leads to situations where people may feel that their lives were empty or not as good as the perfect lives they saw on social media, leading to increased feelings of isolation, and making it even more difficult to reach out to others.

“We know that when we're in our deepest despair, with being isolated, [social media] makes it worse and it is a big risk factor. We're in for added trouble,” Brendel said.

What to do

As officials look for answers, experts say there are no simple solutions to such complicated issues.

Top of mind for many mass shooting health experts is addressing the overarching issues with gun control reform in the U.S.

According to polling from Pew Research, nearly half of adults — 49% — say there would be fewer mass shootings if it was harder for people to obtain guns legally.

“The United States is such a blaming society. Once we blame somebody then we can say, ‘oh, our work is done.’ And the answer is no, you haven't done, and prevented anything,” Hemingway said. “You want a system so it's hard for people to get these lethal weapons. It's hard for people to use these lethal weapons, and it's unlikely for people to be so enraged that they want to use these lethal weapons.”

Stigmatization of mental illness is only deterring people from seeking help, experts said.

Thus, ensuring those in need are able to access the care — for mental health, crisis, or stress related issues — without fear of being ostracized or judged, will also be critical.

In getting people the help they need, Dvoskin added that “you would prevent some mass shootings — you would just never know it because you don't know which particular person in crisis is going to do something that's horrific.”

“When you blame mass homicides on mentally ill, all you're doing is dramatically increasing stigma. People don't want to join the group of people who are responsible for harm,” Dvoskin said. “Those statements not only are wrong but they are directly harmful to citizens who might be struggling with a mental illness, but they haven't asked for help, and why would they when we stigmatize it so drastically.”