Coronavirus testing: What top officials say went wrong

"Testing has been the Achilles' heel of our outbreak response," expert says.

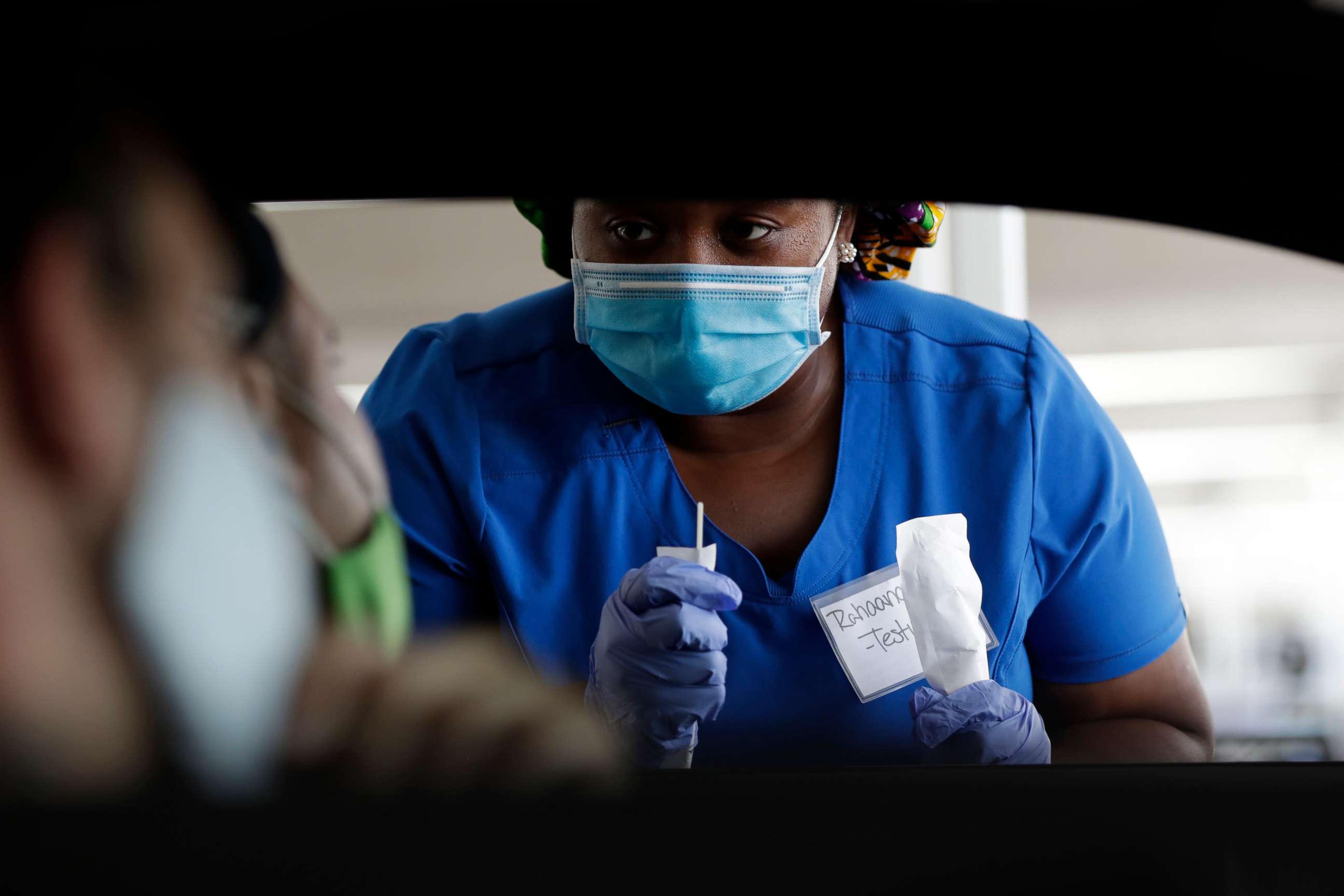

If you can’t cure a contagious disease, the next best thing, according to the experts, is to find it and identify those who need to be isolated through aggressive, widespread testing.

That’s one reason countries like South Korea and Germany have so far largely managed to keep coronavirus under control. But in the U.S. public health experts, as well as those in charge of the response to the coronavirus pandemic, told ABC News that from the start the nation’s testing program has never been where it needs to be, from costly mistakes early on to ongoing bottlenecks.

“Testing has been the Achilles' heel of our outbreak response nationally and locally, from the get-go,” said Dr. Jeffrey Duchin, Public Health Officer for Seattle-King County, in Washington state where the first case of COVID-19 in the U.S. was identified.

In detailed interviews with ABC News as part of the "20/20" special report "American Catastrophe: How Did We Get Here?", senior Trump officials in charge of designing and distributing the nation's coronavirus test now acknowledge the problems that stifled an early, robust screening for the virus, while generally defending their agencies' actions. Critics said the flaws cost the nation crucial time at a critical point in the outbreak.

And now, six months after the federal government identified the first case of coronavirus on U.S. soil, lines for COVID-19 testing in some cities are still backing up daily, and many people are still reporting lengthy waits before they receive results. Some senior Trump administration officials acknowledge the ongoing problems, but struggle to explain why they have not be resolved.

“We keep hearing when we go to these task force meetings that these are being corrected, that is being corrected,” Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease, told ABC News.

“But yet, when you go into the trenches, you still hear about that. I really, quite frankly, have to be honest with you. I cannot explain that," he said.

'They weren't working': A testing fail out of the gate

The effort to develop a reliable test to detect the novel coronavirus struggled from the start.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration began collaborating on a diagnostic test for the coronavirus in January. The CDC, led by Dr. Robert Redfield, began distributing the test kits to public labs in February.

The first U.S. case of coronavirus had been identified by the CDC on Jan. 21 and the race was on to contain the virus early.

“So these tests were undergoing verification at public health labs, and they spotted a problem almost immediately,” said Scott Becker, chief executive officer of the Association of Public Health Laboratories. “They weren’t working.”

That meant, to Becker, “The biggest tool in our toolbox was missing at this point."

Redfield defended the initial government-designed test, telling ABC News the product itself was never the issue. He explained that in manufacturing one of the tests, one of the chemicals needed for the test to function got contaminated.

“The CDC test that we developed was an excellent test. It was never faulty. And from the day we developed to today as I sit here today -- provided the ability to get eyes on this new pandemic and diagnose cases around the world,” Redfield said.

Still, Redfield acknowledged the CDC had to send out new tests to state and local health departments, a process that he said took four to five weeks. Redfield said that the correction was made in still "pretty record time."

Dr. Charity Dean called it precious time lost.

"As the weeks ticked by, we were running out of time to contain this virus," said Dean, a former assistant director of the California Department of Public Health. "Let me be very clear, in an outbreak scenario, every day matters, every hour matters."

Dr. Dan Hanfling, a contributing scholar at the Center for Biosecurity, said he believes the CDC made a number of strategic and tactical errors -- the largest being that they decided to control the management of the testing capability and the reagents that would be used to test for the virus.

“And it was a fail,” Hanfling said. “And that really set us back.”

Redfield told ABC News he sees now it would've been better to bring in private companies earlier, some of whom he said were initially hesitant to get involved in developing tests.

During past pandemic threats, private sector companies moved quickly to develop tests, Redfield said. But when the viral threats dissipated, they could not make any money off the tests they had raced to produce.

“By the time they developed the test there was no market for the test,” Redfield said. “So I do think the private sector wasn't quite ‘all in’ in developing a coronavirus test back in January and February."

"But I think in retrospect if it had been stimulated more, it would have been a great benefit," he said.

Another problem arises: Testing equipment in the stockpile

As the CDC was sorting out its own test manufacturing issues, on March 12, Adm. Brett Giroir, the Assistant Secretary for Health at Health and Human Services, was asked to take charge of the overall testing program -- an undertaking he described as “an all out-sprint” since that day.

It was also one where the first hurdle for getting enough tests to enough people appeared right away.

Giroir said the nation had a network of storage facilities scattered across the country known as the Strategic National Stockpile, but they lacked sufficient testing supplies, like swabs, that would be needed for mass testing.

“So when I looked to see what was there, there was nothing there,” Giroir told ABC News, in an echo of President Trump's oft repeated complaint that the "cupboards were bare," despite the president having been in office for three years by the start of the U.S. outbreak. “We needed these strange things called swabs. Who makes swabs?"

Giroir said the discovery gave him a “sinking feeling.”

“There was no playbook for diagnostics. There's no game plan. There was nothing,” Giroir said. “We really needed to start from square one.”

The U.S. was short enough on testing equipment that Giroir said he once sent a C-17 cargo plane to Italy to pick up swabs from a small company there.

At the time Giroir was tapped to head the testing operation in mid-March cases in the U.S. numbered in the low thousands, according to a count by Johns Hopkins University, but those were only the one the government knew about.

Despite President Trump's assurance that anyone who "wants a test can get a test," because of testing shortages and with the federal government's guidance, many locations rationed their tests for only the obviously symptomatic or those most at risk. That meant that countless people with the virus who showed mild or no symptoms but could still spread it were likely slipping through the cracks -- unaware to their infection and likely coming in contact with more and more people.

Around the time of Giroir's appointment, Fauci, the infectious disease expert, acknowledged the problem to lawmakers, noting that by that point short of 23,000 tests had been analyzed by the CDC and public health labs.

"The system is not really geared to what we need right now, what you're asking for. That is a failing," he said.

Over the ensuing weeks and months, testing capacity increased significantly, but it could never get ahead of the spread of the virus.

The response system the U.S. government had put in place to rapidly diagnose an outbreak was perfect to mount a relatively small-scale response, Giroir told ABC News, in the nature of hundreds or thousands of cases.

But before even March was over the known case count in the U.S. topped 100,000 and would fly past 1 million approximately 30 days after that -- with testing restrictions remaining in many places.

"It was not meant to support a full-blown pandemic," he said, of the government's overall response plan. "It's not what it was built for."

Giroir said he believes the lack of testing supplies stems from a failure in planning that dates back well before the Trump administration – an assertion that experts acknowledged was likely the case.

An initial stockpile of testing supplies “would have helped us” during the hurried early days, Becker said.

'We have this under control, if we all work together'

Six months after the start of the outbreak the U.S. is still struggling to get testing up to speed, and some local officials have continued to criticize the administration for the lack of coherent testing plan.

The U.S. has now conducted more than 50 million tests and currently gets results from more than 700,000 daily, according to The Atlantic's COVID Tracking Project. But experts say still many more will be necessary to successfully trace the stealthy virus, and labs that analyze the tests are reporting they're already overwhelmed with the current caseloads.

Officials in more than a dozen states told ABC News earlier this month that they've experienced issues in the testing supply chain, from a lack of testing kits to significant delays in getting results from labs.

“We haven’t been able to surge the testing supplies as much as nature has been able to surge cases,” Dr. Helmut Albretch, chair of Department of Internal Medicine Prisma Health Midlands in South Carolina, said. “The more cases you have the more you have to test -- we don’t have that surge capability with testing.”

Giroir has emphasized the importance of faster turnaround times for test results and says he and his colleagues try every day to be completely transparent with the American people about the severity of the virus.

Of the battle against the virus in general, Giroir said, "I hope everybody understands that this is a serious situation. We're in a much better position [than] we were three months ago.

"We're never gonna be satisfied 'til this is over," he said. "But we have this under control, if we all work together.”

What to know about coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map