Doctors race to find out more about polio-like disorder AFM before next wave of illnesses

AFM strikes quickly, mostly in children, first appearing like a normal cold.

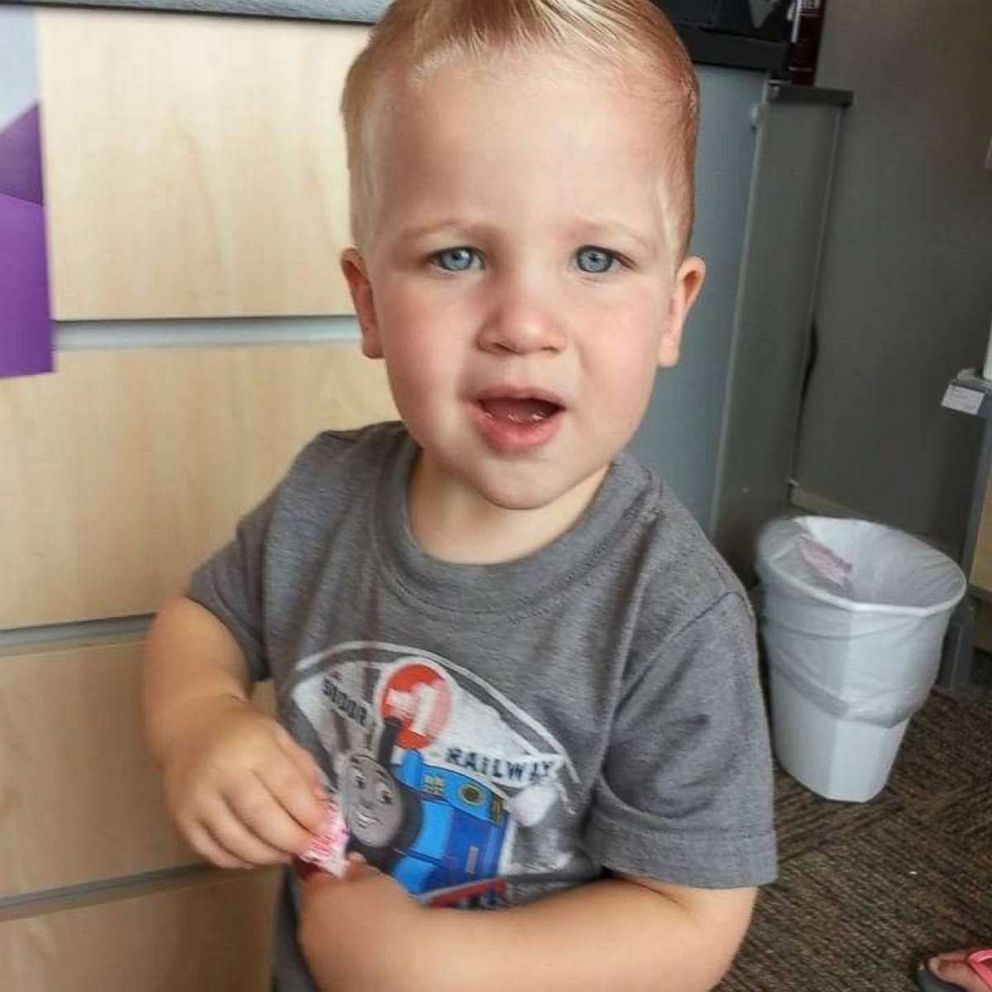

Four-year-old Camdyn Carr began the fight of his life two months ago at the Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, Maryland, where he was first diagnosed with acute flaccid myelitis (AFM).

The Carr family have remained steady in the battle as their child’s body fights a modern day medical mystery that left him mostly paralyzed and nearly killed him.

“I'm grateful he's getting better and I know it's a long process,” his father Chris Carr told ABC News.

AFM is a devastating illness that is being compared to a modern day Polio because of their similar paralyzing symptoms. It has stricken 543 children in the United States since 2014. It has no vaccine or cure and the cause is unclear.

AFM strikes quickly and mostly in children -- first appearing like a normal cold -- but in its wake, victims are left in a state of partial or full paralysis, that can lead to death.

“You’d never think it would happen to you ... ‘cause Lord knows I would not have ever thought, I never even heard of AFM before he got sick. Prepare for the worst and pray for the best,” the father said.

After a sudden 2014 outbreak of AFM, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) created a task force of health professionals. They were tasked with researching and tracking the emergence of the disorder.

Since then, there have been increasing numbers of cases every two years that have led doctors to some answers.

Dr. Benjamin Greenberg, of UT Southwestern Medical Center’s O’Donnell Brain Institute, is a specialist who has worked with the CDC and has treated patients with AFM since 2009, well before the 2014 outbreak. He's one of several doctors across the country trying to solve this mystery.

“We know there are a lot of different causes of paralysis in children. There are a number of different viruses certain autoimmune conditions that can lead to the exact same symptoms and the exact same findings on an MRI at the same time,” he explained. "Not every child who develops the syndrome of acute flaccid myelitis has been infected with an enterovirus, but our read of the data says that between July and November during ... 2014, 2016 and 2018 that the majority of children were probably impacted by this group of enteroviruses that year.”

Because of this, experts believe there is a link between occurrence of specific viruses and why outbreaks of AFM happen in two year cycles. With the clock ticking before the next emergence, officials like Dr. Greenberg fear it could become even worse.

The concern is that “it could mutate to become more virulent and cause more cases of paralysis over years to come and nobody knows the answer to that,” Greenberg said.

The latest outbreak began making headlines across the country last October when six children in Minnesota were diagnosed with AFM.

Those children, along with Camdyn Carr, are part of at least 210 children across 40 states to contract AFM in the 2018 outbreak and until doctors better understand the illness, physical therapy is one of the only treatments that can help.

Courtney Porter, Carr’s therapist, said when she first met Carr, he had “a lot of anxiety.”

“He was very afraid of everything that we did here, even just getting from his bed into the wheelchair, from the wheelchair onto our mat tables, were very nerve-inducing things [that] required a lot of distraction and play to get him to be able to do those types of things,” Porter said.

Carr likely faces a lifetime of recovery.

“It’s definitely a long progress for the kids,” Porter said.

But in her time with the now 4-year-old, Porter said his progress “is really promising.”

“To even just see the movement in his left leg now that he didn't show at all just a couple of months ago is really exciting to see,” she said.

As more children have become ill with AFM, families have called on state and federal health officials to do more.

Chris Carr traveled to Washington, D.C., in November with several other families and met with members of Congress and representatives from the CDC.

“I’m kinda glad that I’m doing it for my son and all the other families that are affected, because people need to know about this,” he said. “It’s already hard enough on people going through this with their children. It’s even harder that you gotta deal with the CDC that’s not doing their job, in my opinion.”

The frustration at health officials has been a growing sentiment that resonated with many other families who have struggled with AFM.

Robin Roberts said her son Carter went from being a perfectly healthy 3-year-old to a quadriplegic in 2014.

“We did everything the CDC said to do. We did everything a pediatrician tells you to do. And this crazy thing still happened to us,” Roberts said.

At the time, doctors who first treated Carter were left scrambling for answers, unsure what was wrong with even less research available about the disorder.

Roberts said they were “dismissed by the first physician” who saw her son, but she insisted that something was wrong.

“There was actually another doctor that came into his curtain a short while later and he said, ‘look I'm worried about a possibility of a meningitis possibly a stroke although that would be pretty atypical or something else going on here,’” Roberts recalled.

It took the doctors 10 days, several spinal taps and an MRI to determine Roberts had AFM, but despite the diagnosis there was not much they could do.

“There was no cure or treatment to do,” the mother said. “Based on everything going on with Carter that nothing was bound to change and to take care of him the best we could and the best we knew how with the complications being hooked up to the ventilator being fed through a tube and stomach.”

For two years, his parents became full time caregivers, putting Carter through intense physical therapy.

Roberts called it a “cadence of chaos” trying to do everything around the clock.

“Coming home doesn't make it go away. It means you're trying to do more with less. You're trying to do all the things that all of those wonderful professionals did for your child to help them be good feel good get better be entertained be happy,” she said. “But it's just mom and dad.”

As attentive and dedicated as Robin and her family were to Carter, it wasn’t enough. On Sept. 22, 2018, after two years of living with AFM, she said her son passed away from respiratory complications related to AFM.

Since his death, the family has pushed health officials to put a greater focus on AFM so that other families don’t have to go through the pain of losing a child like they did.

“I think the CDC could be following these cases more closely,” Roberts said, suggesting they follow the illness “on a long term basis to make sure they know what's happening to these kids.”

She continued, “I applaud them for putting together the task force that just recently started. But I think the efforts of those sort of work groups are long overdue. And they must be maintained and have sustainability into the future.”

The CDC has yet to acknowledge her son’s death was a result of AFM.

The CDC said in a statement to "Nightline" that they are "very concerned about AFM."

"Since 2014, we have learned important information about the cases and outbreaks. Unfortunately, there’s a lot that we still don’t know about this rare and complex condition. CDC is committed to finding out what causes AFM cases and what factors might be linked to greater risk. We have established an AFM task force of national experts to help us develop a comprehensive research agenda. We value the experiences and stories of parents whose children have AFM and pledge to work with them to find the cause."

“I think they need to accelerate the dialogue and the work around acute flaccid myelitis to find out what's causing this,” Roberts proposed. “[To] find out how the disease progresses so that we can better understand how to intervene or mitigate it to begin with.”

“It must be accelerated or more children are going to die,” she said.

The CDC has previously said they didn’t do as much as they should have with record keeping and they are going back and revising the numbers from previous years.

Dr. Greenberg said “there is room for improvement across the board relative to how we approach AFM.”

Camdyn Carr returned home in December. As his family continues to battle AFM, his dad is doing what he can to keep a firm hold on hope.

Chis Carr said he feels for the families that have lost a child, but is “just hoping that my son is different from the others.”

“I could not imagine what they go through, but I just hope that’s not my child at the same,” he said.