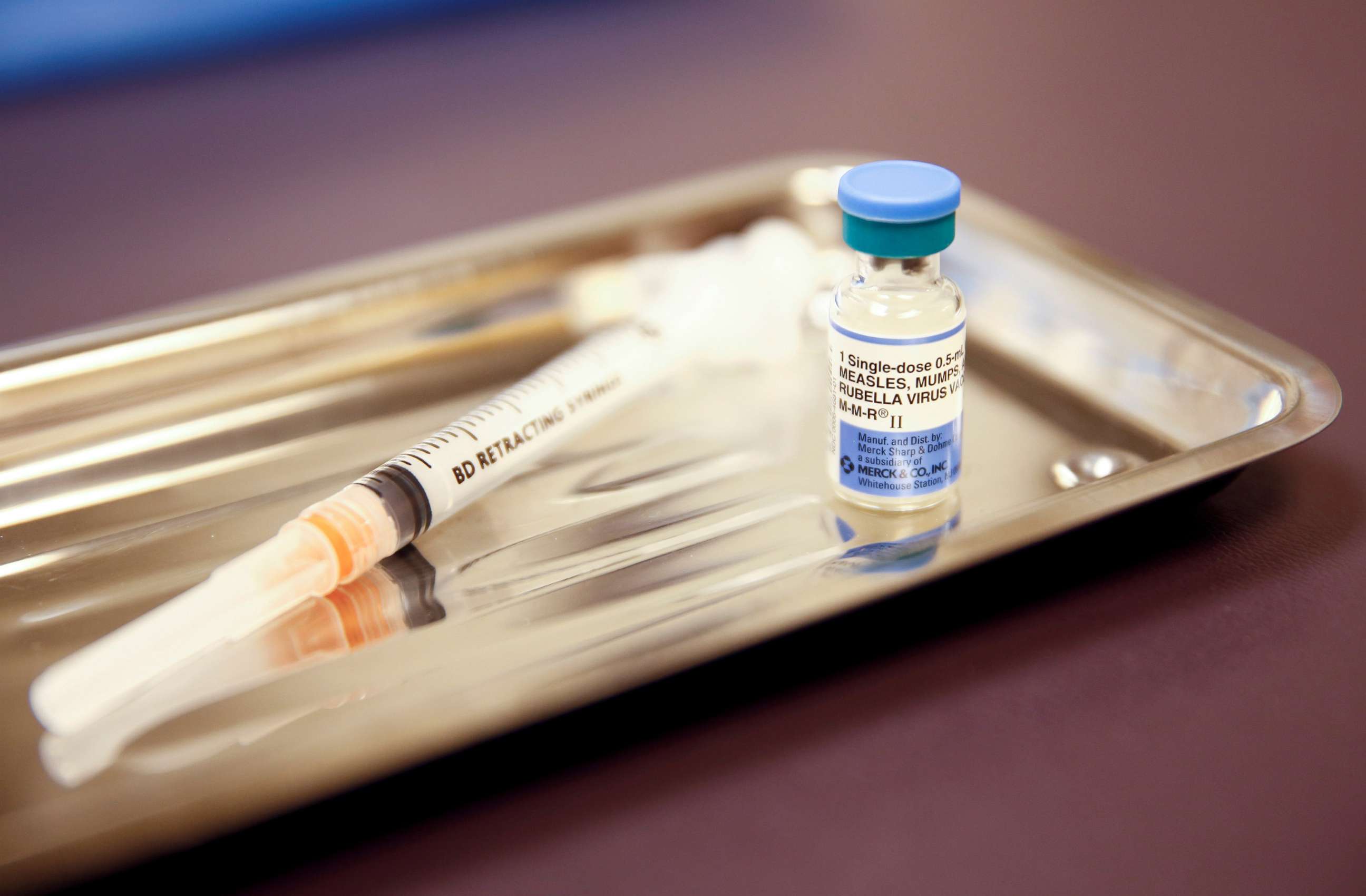

The high price of low vaccination rates: How a single measles outbreak cost $3.4 million

The anti-vax movement can be expensive for society writ large, a study finds.

Measles, a disease long thought eliminated from the Western Hemisphere, re-emerged in Washington state in early 2019 -- 72 people were infected, 61 of whom were unvaccinated.

A new analysis just published in The American Academy of Pediatrics finds that the outbreak was not only harmful to the individual health of dozens, it cost society an estimated $3.4 million.

"A disease like measles is so serious because it is so contagious. Some of the greatest costs come from the public health response and contact-tracing efforts," Dr. Blythe Adamson, an infectious disease epidemiologist and economist and affiliate professor at University of Washington, told ABC News.

Diseases like COVID also require extensive contact-tracing efforts, generating extra societal costs beyond loss of life and financial losses incurred by the sick.

Many wonder why vaccine uptake isn't 100%. Experts say it's because of a variety of factors -- myths regarding safety, myths that vaccines were rushed through scientific trials, myths that vaccines cause autism, aversion to government mandates and general distrust of the medical system.

"The anti-vaccine movement not only cost lives but also money," Dr. Amesh A. Adalja, senior scholar at Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, told ABC News. And experts say the recent re-emergence of diseases like measles offers a stark reminder that vaccinations can help reduce future infectious disease outbreaks -- and limit societal costs.

The 2019 measles outbreak occurred in Clark County, just south of Seattle, where measles vaccine uptake was estimated to be as low as 78%, compared with an estimated national average of 94%. Scientists estimate at least 90% of a population must be vaccinated against measles to create herd immunity.

Investigators estimated that this outbreak led to societal costs of approximately $47,479 per measles case, and $814 per contact -- about $3.4 million overall. Much of the cost was related to the public health response, followed by productivity losses and then direct medical care. The 72 infected individuals had 4,011 contacts, over 20% of whom were unvaccinated and therefore susceptible.

"When it comes to measles," Adalja said, "several studies have come to the exact same conclusion: That not only is the vaccine life-saving, it is extremely cost effective."

Experts have many ideas about how to get vaccination efforts back on track, not just for measles but for other diseases, including COVID-19.

"I think you need to drive home the point that vaccines work incredibly well," said Dr. Paul Goepfert, director of the Alabama Vaccine Research Clinic. "You need to have a national campaign to show the importance. ... I think if Donald Trump and Melania Trump would have come out right afterwards to say, 'We got the vaccine, you should too,' that would go a long way toward getting his supporters to get the vaccine."

"There's not any type of one-size-fits all [solution] for any of this," said Dr. Tara Smith, a professor of epidemiology at Kent State University's College of Public Health. "The way to combat this is to build trust, have conversations and work with people about their individual [concerns]."

"The first thing we should be doing is just listening to them, trying to understand what their specific and unique reasons are," said Adamson, who agrees that respected members of different communities understanding and endorsing vaccine efficacy can be very effective, whether it's a pastor or an Alcoholics Anonymous group leader. And it's important to acknowledge why some communities "have historical reasons why they mistrust the medical community."

A better understanding of the potential economic toll associated with lower vaccine uptake could be used to improve public policy, perhaps by implementing more public health interventions, experts said.

"In the long run," Adamson said, such interventions "may be cost-saving for the community."

Zachary Orlins, D.O., a resident physician in psychiatry at Cleveland Clinic, is a contributor to the ABC News Medical Unit.